THE ENTROPY CHANGE OF IDEAL GASES

An expression for the entropy change of an ideal gas can be obtained from Eq. 7–25 or 7–26 by employing the property relations for ideal gases (Fig. 7–31). By substituting du = Cu dT and P = RT/u into Eq. 7–25, the differential entropy change of an ideal gas becomes

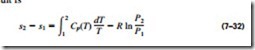

A second relation for the entropy change of an ideal gas is obtained in a similar manner by substituting dh = Cp dT and u = RT/P into Eq. 7–26 and integrating. The result is

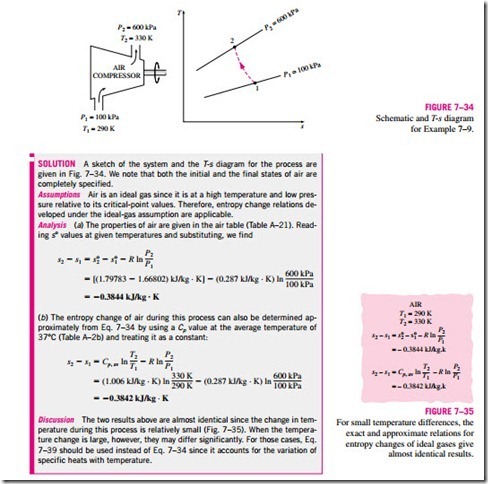

The specific heats of ideal gases, with the exception of monatomic gases, de- pend on temperature, and the integrals in Eqs. 7–31 and 7–32 cannot be per- formed unless the dependence of Cu and Cp on temperature is known. Even when the Cu(T) and Cp(T) functions are available, performing long integrations every time entropy change is calculated is not practical. Then two reasonable choices are left: either perform these integrations by simply assuming constant specific heats or evaluate those integrals once and tabulate the results. Both approaches are presented next.

Constant Specific Heats (Approximate Analysis)

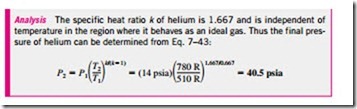

Assuming constant specific heats for ideal gases is a common approximation, and we used this assumption before on several occasions. It usually simplifies the analysis greatly, and the price we pay for this convenience is some loss in accuracy. The magnitude of the error introduced by this assumption depends on the situation at hand. For example, for monatomic ideal gases such as helium, the specific heats are independent of temperature, and therefore the constant-specific-heat assumption introduces no error. For ideal gases whose specific heats vary almost linearly in the temperature range of interest, the possible error is minimized by using specific heat values evaluated at the av- erage temperature (Fig. 7–32). The results obtained in this way usually are sufficiently accurate if the temperature range is not greater than a few hundred degrees.

The entropy-change relations for ideal gases under the constant-specific-heat assumption are easily obtained by replacing Cu(T) and Cp(T) in Eqs. 7–31 and 7–32 by Cu, av and Cp, av, respectively, and performing the integrations. We obtain

Variable Specific Heats (Exact Analysis)

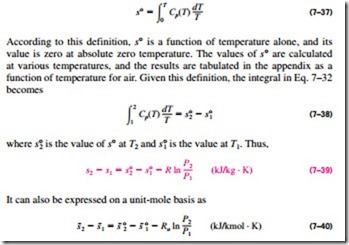

When the temperature change during a process is large and the specific heats of the ideal gas vary nonlinearly within the temperature range, the assumption of constant specific heats may lead to considerable errors in entropy-change calculations. For those cases, the variation of specific heats with temperature should be properly accounted for by utilizing accurate relations for the specific heats as a function of temperature. The entropy change during a process is then determined by substituting these Cu(T) or Cp(T) relations into Eq. 7–31 or 7–32 and performing the integrations.

Instead of performing these laborious integrals each time we have a new process, it is convenient to perform these integrals once and tabulate the results. For this purpose, we choose absolute zero as the reference temperature and define a function s° as

Note that unlike internal energy and enthalpy, the entropy of an ideal gas varies with specific volume or pressure as well as the temperature. Therefore, entropy cannot be tabulated as a function of temperature alone. The s° values in the tables account for the temperature dependence of entropy (Fig. 7–33).

The entropy of an ideal gas depends on both T and P. The function s° represents only the temperature- dependent part of entropy.

The variation of entropy with pressure is accounted for by the last term in Eq. 7–39. Another relation for entropy change can be developed based on Eq. 7–31, but this would require the definition of another function and tabula- tion of its values, which is not practical.

Isentropic Processes of Ideal Gases

Several relations for the isentropic processes of ideal gases can be obtained by setting the entropy-change relations developed above equal to zero. Again, this is done first for the case of constant specific heats and then for the case of variable specific heats.

Constant Specific Heats (Approximate Analysis)

When the constant-specific-heat assumption is valid, the isentropic relations for ideal gases are obtained by setting Eqs. 7–33 and 7–34 equal to zero. From Eq. 7–33,

The specific heat ratio k, in general, varies with temperature, and thus an average k value for the given temperature range should be used.

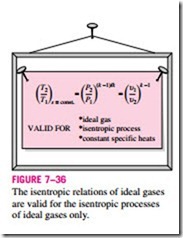

Note that the ideal-gas isentropic relations above, as the name implies, are strictly valid for isentropic processes only when the constant-specific-heat assumption is appropriate (Fig. 7–36).

Variable Specific Heats (Exact Analysis)

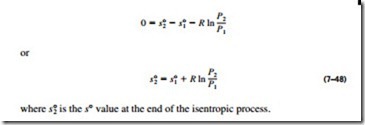

When the constant-specific-heat assumption is not appropriate, the isentropic relations developed above will yield results that are not quite accurate. For such cases, we should use an isentropic relation obtained from Eq. 7–39 that accounts for the variation of specific heats with temperature. Setting this equation equal to zero gives

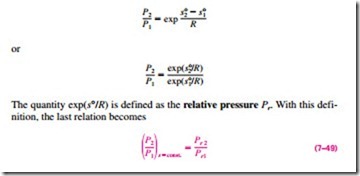

Relative Pressure and Relative Specific Volume Equation 7–48 provides an accurate way of evaluating property changes of ideal gases during isentropic processes since it accounts for the variation of specific heats with temperature. However, it involves tedious iterations when the volume ratio is given instead of the pressure ratio. This is quite an inconvenience in optimization studies, which usually require numerous repetitive calculations. To remedy this deficiency, we define two new dimensionless quantities associated with isentropic processes.

The definition of the first is based on Eq. 7–48, which can be rearranged as

Note that the relative pressure Pr is a dimensionless quantity that is a function of temperature only since s° depends on temperature alone. Therefore, values of Pr can be tabulated against temperature. This is done for air in Table A–21. The use of Pr data is illustrated in Fig. 7–37.

Process: isentropic Given: P1, T1, and P2 Find: T2

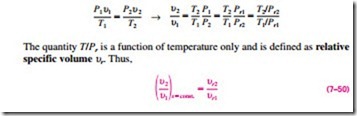

Sometimes specific volume ratios are given instead of pressure ratios. This is particularly the case when automotive engines are analyzed. In such cases, one needs to work with volume ratios. Therefore, we define another quantity related to specific volume ratios for isentropic processes. This is done by utilizing the ideal-gas relation and Eq. 7–49:

Equations 7–49 and 7–50 are strictly valid for isentropic processes of ideal gases only. They account for the variation of specific heats with temperature and therefore give more accurate results than Eqs. 7–42 through 7–47. The values of Pr and ur are listed for air in Table A–21.