PARALLEL FLOW OVER FLAT PLATES

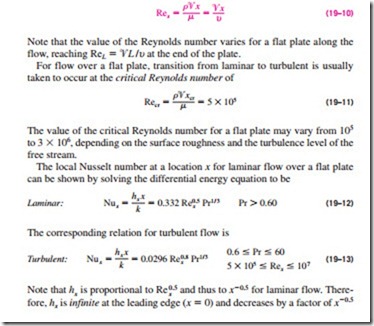

Consider the parallel flow of a fluid over a flat plate of length L in the flow direction, as shown in Fig. 19–8. The x-coordinate is measured along the plate surface from the leading edge in the direction of the flow. The fluid approaches the plate in the x-direction with uniform upstream velocity ‘V and temperature Too. The flow in the velocity boundary layer starts out as laminar, but if the plate is sufficiently long, the flow will become turbulent at a distance xcr from the leading edge where the Reynolds number reaches its critical value for transition.

The transition from laminar to turbulent flow depends on the surface geometry, surface roughness, upstream velocity, surface temperature, and the type of fluid, among other things, and is best characterized by the Reynolds number. The Reynolds number at a distance x from the leading edge of a flat plate is expressed as

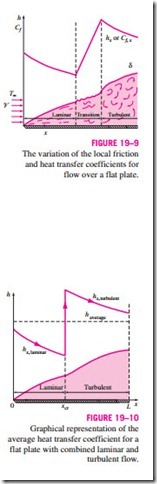

in the flow direction. The variation of the boundary layer thickness d and the friction and heat transfer coefficients along an isothermal flat plate are shown in Fig. 19–9. The local friction and heat transfer coefficients are higher in tur- h bulent flow than they are in laminar flow. Also, hx reaches its highest values Cf when the flow becomes fully turbulent, and then decreases by a factor of x-0.2 in the flow direction, as shown in the figure.

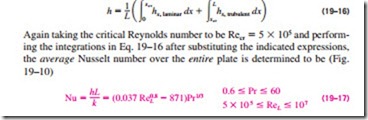

The average Nusselt number over the entire plate is determined by substituting the preceding relations into Eq. 19–5 and performing the integrations. We get

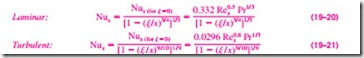

The first relation gives the average heat transfer coefficient for the entire plate when the flow is laminar over the entire plate. The second relation gives the average heat transfer coefficient for the entire plate only when the flow is turbulent over the entire plate, or when the laminar flow region of the plate is too small relative to the turbulent flow region.

In some cases, a flat plate is sufficiently long for the flow to become turbulent, but not long enough to disregard the laminar flow region. In such cases, the average heat transfer coefficient over the entire plate is determined by per- forming the integration in Eq. 19–5 over two parts as

The constants in this relation will be different for different critical Reynolds numbers.

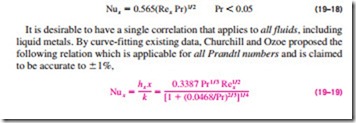

Liquid metals such as mercury have high thermal conductivities, and are commonly used in applications that require high heat transfer rates. However, they have very small Prandtl numbers, and thus the thermal boundary layer develops much faster than the velocity boundary layer. Then we can assume the velocity in the thermal boundary layer to be constant at the free-stream value and solve the energy equation. It gives

These relations have been obtained for the case of isothermal surfaces but could also be used approximately for the case of nonisothermal surfaces by assuming the surface temperature to be constant at some average value. Also, the surfaces are assumed to be smooth, and the free stream to be turbulent free. The effect of variable properties can be accounted for by evaluating all properties at the film temperature.

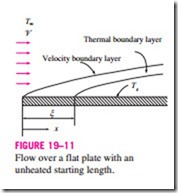

Flat Plate with Unheated Starting Length

So far we have limited our consideration to situations for which the entire plate is heated from the leading edge. But many practical applications involve surfaces with an unheated starting section of length j, shown in Fig. 19–11, and thus there is no heat transfer for 0 < x < j. In such cases, the velocity boundary layer starts to develop at the leading edge (x = 0), but the thermal boundary layer starts to develop where heating starts (x = j).

Consider a flat plate whose heated section is maintained at a constant tem- perature (T = Ts constant for x > j). Using integral solution methods (see Kays and Crawford, 1994), the local Nusselt numbers for both laminar and

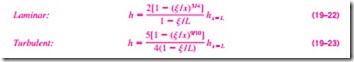

for x > j. Note that for j = 0, these Nux relations reduce to Nux (for j = 0), which is the Nusselt number relation for a flat plate without an unheated starting length. Therefore, the terms in brackets in the denominator serve as correction factors for plates with unheated starting lengths.

The determination of the average Nusselt number for the heated section of a plate requires the integration of the local Nusselt number relations above, which cannot be done analytically. Therefore, integrations must be done nu- merically. The results of numerical integrations have been correlated for the average convection coefficients [Thomas (1977) as

The first relation gives the average convection coefficient for the entire heated section of the plate when the flow is laminar over the entire plate. Note that for j = 0 it reduces to hL = 2hx = L , as expected. The second relation gives the average convection coefficient for the case of turbulent flow over the en- tire plate or when the laminar flow region is small relative to the turbulent region.

Uniform Heat Flux

When a flat plate is subjected to uniform heat flux instead of uniform temperature, the local Nusselt number is given by

These relations give values that are 36 percent higher for laminar flow and 4 percent higher for turbulent flow relative to the isothermal plate case. When the plate involves an unheated starting length, the relations developed for the uniform surface temperature case can still be used provided that Eqs. 19–24 and 19–25 are used for Nux(for j = 0) in Eqs. 19–20 and 19–21, respectively.

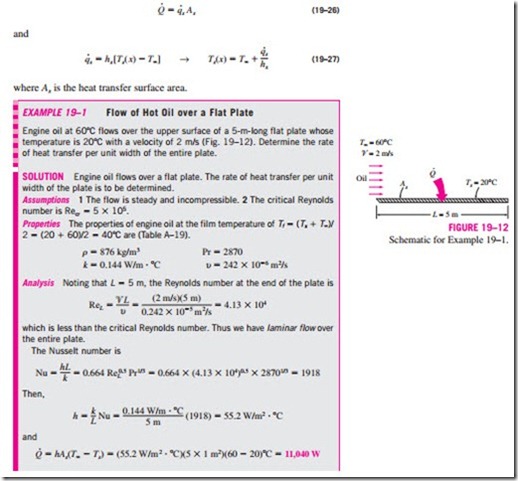

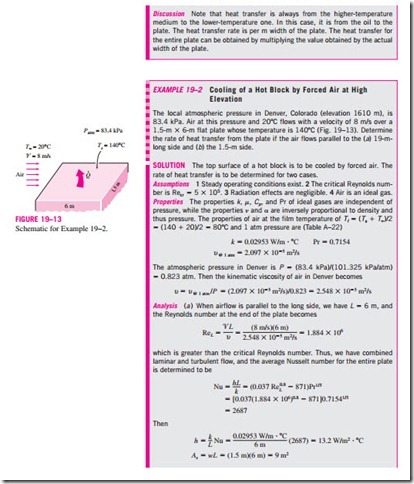

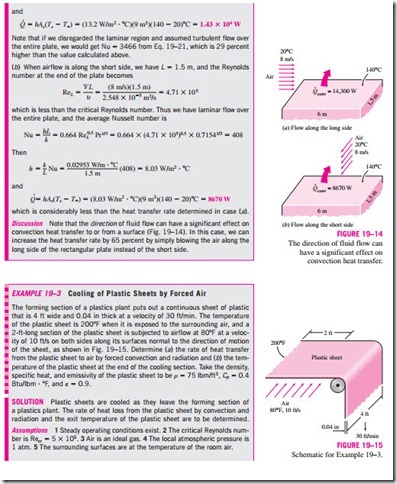

When heat flux is prescribed, the rate of heat transfer to or from the plate and the surface temperature at a distance x are determined from