Filters

Dirt in a hydraulic system causes sticking valves, failure of seals and premature wear. Even particles of dirt as small as 20 Jl can cause damage, ( 1 micron is one millionth of a metre; the naked eye is just able to resolve 40 J.t). Filters are used to prevent dirt entering the vulnerable parts of the system, and are generally specified in microns or meshes per linear inch (sieve number).

Inlet lines are usually fitted with strainers inside the tank, but these are coarse wire mesh elements only suitable for removing relatively large metal particles and similar contaminants Separate filters are needed to remove finer particles and can be installed in three places as shown in Figures 2.19a to c.

Inlet line filters protect the pump, but must be designed to give a low pressure drop or the pump will not be able to raise fluid from the tank. Low pressure drop implies a coarse filter or a large physical size.

Pressure line filters placed after the pump protect valves and actuators and can be finer and smaller. They must, however, be able to withstand full system operating pressure. Most systems use pressure line filtering.

Return line filters may have a relatively high pressure drop and can, consequently, be very fine. They serve to protect pumps by limiting size of particles returned to the tank. These filters only have to withstand a low pressure. Filters can also be classified as full or proportional flow. In Figure 2.20a, all flow passes through the filter. This is obviously efficient in terms of filtration, but incurs a large pressure drop. This pressure drop increases as the filter becomes polluted, so a full flow filter usually incorporates a relief valve which cracks when the filter becomes unacceptably blocked. This is purely a safety feature, though, and the filter should, of course, have been changed before this state was reached as dirty unfiltered fluid would be passing round the system.

In Figure 2.20b, the main flow passes through a venturi, creating a localised low pressure area. The pressure differential across the filter element draws a proportion of the fluid through the filter. This design is accordingly known as a proportional flow filter, as only a proportion of the main flow is filtered. It is characterized by a low pressure drop, and does not need the protection of a pressure relief valve.

Pressure drop across the filter element is an accurate indication of its cleanliness, and many filters incorporate a differential pressure meter calibrated with a green (clear), amber (warning), red (change overdue) indicator. Such types are called indicating filters.

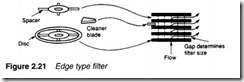

Filtration material used in a filler may be mechanical or absorbent. Mechanical filters are relatively coarse, and utilise fine wire mesh or a disc/screen arrangement as shown in the edge type filter of Figure 2.21. Absorbent filters are based on porous materials such as paper, cotton or cellulose. Filtration size in an absorbent filter can be very small as filtration is done by pores in the material. Mechanical filters can usually be removed, cleaned and re-fitted, whereas absorbent filters are usually replaceable items.

In many systems where the main use is the application of pressure the actual draw from the tank is very small reducing the effectiveness of pressure and return line filters. Here a separate circulating pump may be used as shown on Figure 2.22 to filter and cool the oil. The running of this pump is normally a pre-condition for starting the main pumps. The circulation pump should be sized to handle the complete tank volume every 10 to 15 minutes.

Note the pressure relief valve- this is included to provide a route back to tank if the filter or cooler is totally blocked. In a real life system additional hand isolation and non return valves would be fitted to permit changing the filter or cooler with the system running. Limit switches and pressure switches would also be included to signal to the control system that the hand isolation valves are open and the filter is clean.