DOLBY SURROUND CONCEPT

The Dolby surround-sound system has its origins in the cinema industry, the original concept being to create a complete surround soundfield from an optically recorded stereo sound stripe-pair on film. Thus compatibility with mono and stereo equipment could be maintained. For mono reproduction the L and R signals are merely added together, and for stereo each is reproduced via its own ampli- fier and speaker, one on each side of the screen. For the surround effect, the left- and right-channel signals are applied to a decoder from which emerge the audio feeds for the several loudspeakers involved.

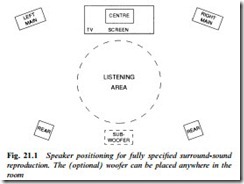

Four channels are used to create the surround effect: Left, Right, Centre, and a fourth called Surround. Left and Right emulate the normal front stereo sounds, while the front centre channel is there to anchor ‘on-screen’ sound, particularly speech and dialogue, to the screen area: this is specially important for viewers on the sides of the listening area. The Surround channel, by contrast, is used to create an ambience or atmosphere behind and around the viewer, and to enhance such effects as thunder, crowd scenes and aircraft flying overhead. In practical home systems the surround signal is generally fed to two speakers at the rear of the viewing room with a time delay, as we shall shortly see. Fig. 21.1 shows the loudspeaker placement in a typical domestic environment, in which the larger the TV screen the more effective is the overall effect.

Since the whole soundfield, in four separate signal streams, has to be carried in just two channels the possibility of crosstalk is there. Some degree of crosstalk among the three front channels is tolerable because the sounds they make are all coming from the general area of the screen. It is important to minimise crosstalk between the centre and surround channels because any significant signal-leakage here would have the effect of dispersing the sound of speech and dialogue in the viewing area and thwarting the ‘tight-targeting’ purpose of the centre channel. To maximise front/back signal separation, time- delay and bandwidth-restriction techniques are used. The rear- channel signal is electrically delayed by a period longer than the acoustic soundwave takes to traverse the room in order that the dialogue is heard first from the front; and the limited bandwidth of rear/surround sound minimises the effects of crosstalk and reduces the perceived directionality of sounds coming from the side and/or rear speakers.

Because the Dolby Surround system depends on phasing of signals in the two transmission or ‘storage’ channels it is vital that they are closely balanced in terms of gain, bandwidth, delay and propagation time.

Surround encoder

Fig. 21.2 shows the basic principle of Dolby Surround encoding. The encoder accepts four separate inputs and generates from them two signals, left-total (Lt) and right-total (Rt). The L and R input signals go directly to the Lt and Rt outputs without modification in order to maintain full stereo compatibility. The C (centre) channel input – having undergonea3 dB level reduction to achieve constant acoustic power in the mix – is simply added to both L and R on their way through. The S (surround) signal is also added to each of L and R, but it first undergoes some special processing. Its frequency spectrum is limited to the range 100 Hz–7 kHz in a bandpass filter, after which it undergoes a noise-reduction process similar to that used in the Dolby B NR system. Finally, plus and minus 90° phase shifts are given to the S signal before its addition to L and R signals respectively, so that there is 180° phase difference (in effect an inversion) of the S signal between Lt and Rt feeds.

Study of the diagram shows that the L and R signals remain independent throughout: there is no crosstalk. Neither is there any crosstalk between centre and surround signals because while the S signal is formed out of the difference between Rt and Lt, the C components in them are identical, and thus cancel out. The centre channel signal is derived from the sum of Lt and Rt, and this sum is immune to the effect of S signals: being equal and opposite they cancel out in the centre output. It is now plain why the two channels carrying Lt and Rt must be closely matched in terms of amplitude and propagation delay. Any shortcoming here introduces crosstalk between C and S channels, and a corresponding loss of realism in the reproduced soundfield.