Differences between European and North American Systems

Distribution systems around the world have evolved into different forms. The two main designs are North American and European. This book deals mainly with North American distribution practices; for more information on European systems, see Lakervi and Holmes (1995). For both forms, hardware is much the same: conductors, cables, insulators, arresters, regulators, and transformers are very similar. Both systems are radial, and voltages and power carrying capabilities are similar. The main differences are in layouts, configurations, and applications.

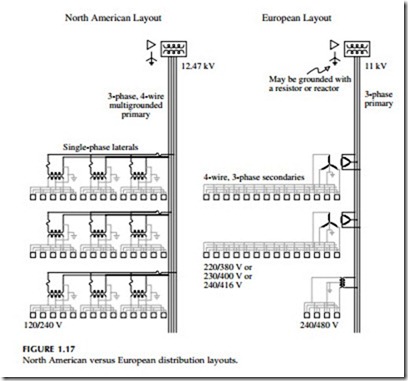

Figure 1.17 compares the two systems. Relative to North American designs, European systems have larger transformers and more customers per trans- former. Most European transformers are three-phase and on the order of 300 to 1000 kVA, much larger than typical North American 25- or 50-kVA single- phase units.

Secondary voltages have motivated many of the differences in distribution systems. North America has standardized on a 120/240-V secondary system; on these, voltage drop constrains how far utilities can run secondaries, typically no more than 250 ft. In European designs, higher secondary volt- ages allow secondaries to stretch to almost 1 mi. European secondaries are largely three-phase and most European countries have a standard secondary voltage of 220, 230, or 240 V, twice the North American standard. With twice the voltage, a circuit feeding the same load can reach four times the distance. And because three-phase secondaries can reach over twice the length of a single-phase secondary, overall, a European secondary can reach eight times the length of an American secondary for a given load and voltage drop. Although it is rare, some European utilities supply rural areas with single-

phase taps made of two phases with single-phase transformers connected phase to phase.

In the European design, secondaries are used much like primary laterals in the North American design. In European designs, the primary is not tapped frequently, and primary-level fuses are not used as much. Euro- pean utilities also do not use reclosing as religiously as North American utilities.

Some of the differences in designs center around the differences in loads and infrastructure. In Europe, the roads and buildings were already in place when the electrical system was developed, so the design had to “fit in.” Secondary is often attached to buildings. In North America, many of the roads and electrical circuits were developed at the same time. Also, in Europe houses are packed together more and are smaller than houses in America.

Each type of system has its advantages. Some of the major differences between systems are the following (see also Carr and McCall, 1992; Meliopoulos et al., 1998; Nguyen et al., 2000):

• Cost — The European system is generally more expensive than the North American system, but there are so many variables that it is hard to compare them on a one-to-one basis. For the types of loads and layouts in Europe, the European system fits quite well. European primary equipment is generally more expensive, especially for areas that can be served by single-phase circuits.

• Flexibility — The North American system has a more flexible primary design, and the European system has a more flexible secondary design. For urban systems, the European system can take advantage of the flexible secondary; for example, transformers can be sited more conveniently. For rural systems and areas where load is spread out, the North American primary system is more flexible. The North American primary is slightly better suited for picking up new load and for circuit upgrades and extensions.

• Safety — The multigrounded neutral of the North American primary system provides many safety benefits; protection can more reliably clear faults, and the neutral acts as a physical barrier, as well as helping to prevent dangerous touch voltages during faults. The European system has the advantage that high-impedance faults are easier to detect.

• Reliability — Generally, North American designs result in fewer customer interruptions. Nguyen et al. (2000) simulated the perfor- mance of the two designs for a hypothetical area and found that the average frequency of interruptions was over 35% higher on the European system. Although European systems have less primary, almost all of it is on the main feeder backbone; loss of the main feeder results in an interruption for all customers on the circuit.

European systems need more switches and other gear to maintain the same level of reliability.

• Power quality — Generally, European systems have fewer voltage sags and momentary interruptions. On a European system, less primary exposure should translate into fewer momentary interrup- tions compared to a North American system that uses fuse saving. The three-wire European system helps protect against sags from line-to-ground faults. A squirrel across a bushing (from line to ground) causes a relatively high impedance fault path that does not sag the voltage much compared to a bolted fault on a well-grounded system. Even if a phase conductor faults to a low-impedance return path (such as a well-grounded secondary neutral), the delta – wye customer transformers provide better immunity to voltage sags, especially if the substation transformer is grounded through a resis- tor or reactor.

• Aesthetics — Having less primary, the European system has an aes- thetic advantage: the secondary is easier to underground or to blend in. For underground systems, fewer transformer locations and longer secondary reach make siting easier.

• Theft — The flexibility of the European secondary system makes power much easier to steal. Developing countries especially have this problem. Secondaries are often strung along or on top of build- ings; this easy access does not require great skill to attach into.

Outside of Europe and North America, both systems are used, and usage typically follows colonial patterns with European practices being more widely used. Some regions of the world have mixed distribution systems, using bits of North American and bits of European practices. The worst mixture is 120-V secondaries with European-style primaries; the low-voltage secondary has limited reach along with the more expensive European pri- mary arrangement.

Higher secondary voltages have been explored (but not implemented to my knowledge) for North American systems to gain flexibility. Higher secondary voltages allow extensive use of secondary, which makes under- grounding easier and reduces costs. Westinghouse engineers contended that both 240/480-V three-wire single-phase and 265/460-V four-wire three- phase secondaries provide cost advantages over a similar 120/240-V three- wire secondary (Lawrence and Griscom, 1956; Lokay and Zimmerman, 1956). Higher secondary voltages do not force higher utilization voltages; a small transformer at each house converts 240 or 265 V to 120 V for lighting and standard outlet use (air conditioners and major appliances can be served directly without the extra transformation). More recently, Bergeron et al. (2000) outline a vision of a distribution system where primary-level distribution voltage is stepped down to an extensive 600-V, three-phase

secondary system. At each house, an electronic transformer converts 600 V to 120/240 V.