Magnetism

Electricity and magnetism are distinct phenomena, but related in the sense that one can be converted into the other. Magnetism can be employed to generate electricity, and electricity can be used to produce motion through magnetic attraction and repulsion.

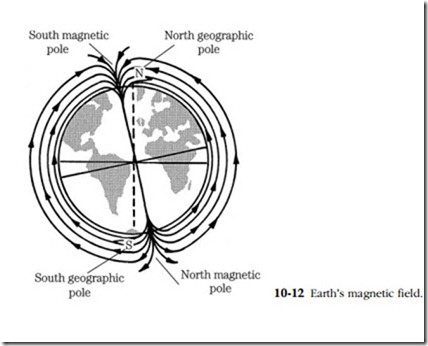

The earth is a giant magnet with magnetic poles located near the geographic poles (Fig. 10-12). Magnetic fields extend between the poles over the surface of the earth and through its core. The field consists of lines of force, or flux. These lines of force have certain characteristics, which, although they do not fully explain the phenomenon, at least allow us to predict its behavior. The lines are said to move from the north to the south magnetic pole just as electrons move from a negative to a positive electrical pole. Magnetic lines of force make closed loops, circling around and through the magnet. The poles are the interface between the internal and external paths of the lines of force. When encountering a foreign body, the lines of force tend to stretch and snap back upon themselves like rubber bands. This characteristic is important in the operation of generators.

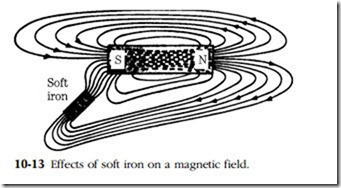

Lines of force penetrate every known substance, as well as the emptiness of outer space. However, they can be deflected by soft iron. This material attracts and focuses flux in a manner analogous to the action of a lens on light. Lines of force ‘prefer’ to travel through iron, and they digress to take advantage of the permeability (magnetic conductivity) of iron (Fig. 10-13).

The permeability of iron is exploited in almost all magnetic machines. Generators, motors, coils, and electromagnets all have iron cores to direct the lines of force most efficiently.

When free to pivot, a magnet aligns itself with a magnetic field, as shown in Fig. 10-14. Unlike magnetic poles attract, like magnetic poles repel. The south magnetic pole of the small magnet (compass needle) points to the north magnetic pole of the large bar magnet.