Radiator Valves

Various valves are required for the efficient operation of radiators.

These valves (or vents) are used to bleed air from the radiator when the heating system first starts. The choice of valve will depend on the requirements of the particular system.

The four principal functions provided by valves operating in conjunction with radiators are as follows:

1. Admission and throttling of the steam or hot-water supply.

2. Expulsion of the air liberated on condensation.

3. Expulsion of air from spaces being filled by steam or hot water.

4. Expulsion of the condensation.

Radiator valves (packed or packless), manual or automatic air valves, and thermostatic expulsion valves (traps) are used to per- form the aforementioned functions.

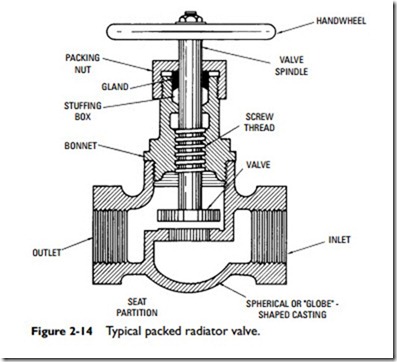

The packed-type radiator valve is an ordinary low-pressure steam valve that has a stuffing box and a fibrous packing to prevent leakage around the stem (see Figure 2-14). The objection to this type of valve is the frequent need for adjustment and renewal of the packing to keep the joint tight. These valves also require many turns of the stem to fully open.

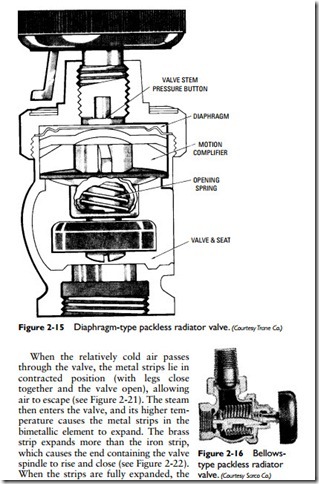

The packless radiator valve is one that has no packing of any kind. Sealing is obtained by means of a diaphragm (see Figure 2-15) or a bellows (see Figure 2-16). On each valve, there is no connection between the actuating element (stem and screw) and the valve being sealed hermetically; hence, there can be no leakage. With the diaphragm arrangement, a spring is used to open the valve. With bellows construction, there is no spring; a shoulder on the end of the stem works in a bearing on the valve inside the bellows.

Some so-called packless radiator valves actually employ spring discs to secure a tight joint. Although called packless, the spring discs form a metallic equivalent of packing.

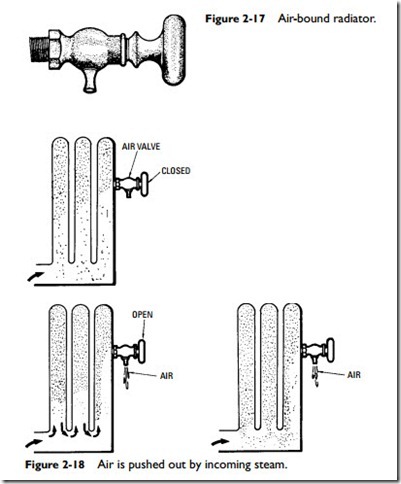

Both manual and automatic air valves are used to remove air from radiators. The manual valves are not well adapted for this function because they usually receive only irregular attention. Air is

constantly forming in the radiator and should be removed as it forms. After the air valve remains closed for some time, the radiator gradu- ally fills with air (or becomes air bound), as shown in Figure 2-17, with the air at the bottom and the steam at the top. On opening the valve (see Figure 2-18), the air is pushed out by the incoming steam. The radiator is gradually filled with steam until it begins to come out of the air valve (see Figure 2-19). At this point, the air valve should be closed.

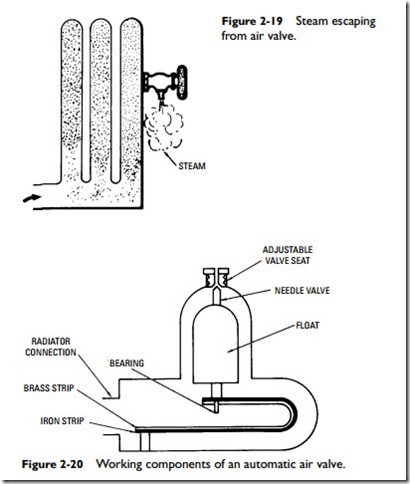

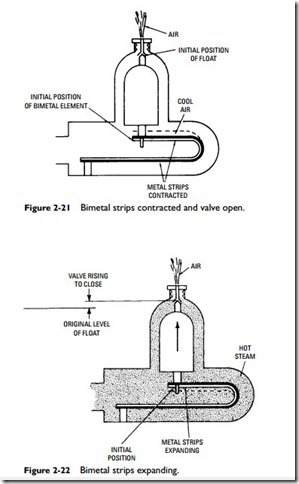

An automatic air valve is one form of the thermostatic valve (see Figure 2-20). Automatic operation is made possible by a bimetallic element contained in the valve. The principles generally employed to secure automatic action are as follows:

1. Expansion and contraction of metals.

2. Expansion and contraction of liquids.

3. Buoyancy of flotation.

4. Air expansion.

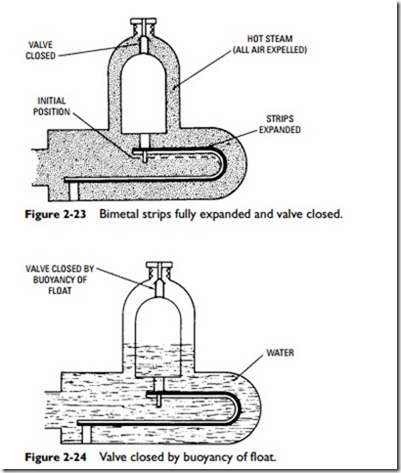

valve is closed, shutting off the escape of steam (see Figure 2-23). In case the radiator becomes flooded with water, the additional water entering will cause the float to push up the valve and prevent the escape of water (see Figure 2-24).

Because an automatic air valve is used only for expelling air from a radiator, it should be distinguished from a thermostatic expulsion valve. A thermostatic expulsion valve opens to air and condensation and closes to steam. The low temperature of the air and condensation causes the bimetallic element to contract and

open the valve, whereas the relatively high temperature of the steam causes the element to expand and close the valve.

Although a thermostatic expulsion valve is sometimes referred to as a trap, this term is more correctly used to indicate a larger unit not connected to a radiator and having the capacity to drain condensation from large mains. As distinguished from the thermostatic valve, a trap handles only condensation and not air.

A bellows charged with a liquid is used on some of the thermo- static valves as an actuating element instead of the bimetallic device.

The operating principle of a Trane bellows-type thermostatic valve is illustrated in Figures 2-25, 2-26, 2-27, and 2-28.

Additional information about valves and valve operating princi- ples is contained in Chapter 9 of Volume 2 (“Valves and Valve Installation”).