Early common-rail

The need for more compact and silent submarine engines led the British arms maker Vickers to develop airless, or solid, injection. One can make the case that the ultimate consumers of nineteenth- and twentieth-century technology were enemy

1 C.L. Cummins, Jr., “Diesel Engines of 2000 BHP per Cylinder—Pre-1914 Marine Engine Developments,” History of the Internal Combustion Engines, ed., E.F.C. Somerscales and A. A. Zagotta, p. 19, 1989.

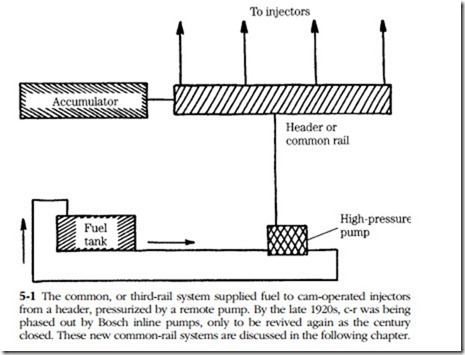

soldiers, sailors, and civilians. At any rate, solid injection was a vast improvement and, after the end of hostilities in 1919, was widely commercialized. Injectors fed from a common rail that was filled with high-pressure fuel and usually fitted with an accumulator to smooth pressure variations generated by injector opening and closing (Fig. 5-1). Adjustable wedges between the camshaft lobes and the injector followers permitted injection duration to vary with speed and load.

Even so, this early form of c-r injection limited engine speed, since increasing the effective width of the wedge by forcing it deeper into contact with the cam also advanced the timing, causing the injector to open earlier. There were also maintenance concerns. According to contemporary accounts, the rails leaked and injectors dribbled fuel throughout the whole operating cycle.