The commercial drive

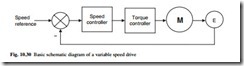

The block schematic shown in Fig.10.30 illustrates the normal arrangement of an inner torque or current loop with an outer speed loop. Alternatively, where torque control is

required in, for example, a tensioning application, then the outer speed loop can be removed, or made subservient to a torque loop with an external torque demand.

However, the modern industrial drive comprises much more than a speed and torque controller. Recent reviews of industrial drive specifications and marketing literature from a broad range of suppliers confirm that the ability to turn the shaft of a motor could be considered a very small part of the feature set of a modern drive. Figure 10.31 is an illustration of the additional functionality frequently found; this generalization changes from supplier to supplier and by the sector of the drive market being considered.

It is rare that an industrial drive stands alone in an application. In the majority of cases, drives are part of a system and it is necessary for the parts of the system to communicate with one another, transmitting commands and data. This communication can be in many forms from traditional analogue signals through to wireless communication systems. The drives industry has been working to produce lower cost, higher performance drives, with good flexible and dynamic interfaces to other industrial products such as PLCs and HMIs. Other suppliers have taken a more holistic view of the needs of their customers, moving from a component supply situation to a solution provider. The ability to interface, efficiently and with appropriate dynamics, with other areas of a machine or factory automation system is of increasing importance in the design of industrial drives. As machine and factory control moves towards more

distributed control structures, the drive will grow in importance as the hub a system controller. To fulfil this role, more flexibility and configurability in drives will result.