Wind-chill

The effect of wind on heat-loss has been known for a long time, but wind-

chill factors have only recently been quoted in weather forecasts to the general public. The principle is that an object located in still air will lose heat comparatively slowly, because the air itself acts as a thermal insulator. Even for a comparatively large temperature difference, then, the rate of loss of heat can be low. When the air is moving, however, its cooling effect is much greater. The layer of air that is in contact with the warm surface is constantly being removed and renewed, taking its heat with it, so that the effect of moving the air is the same as the effect of being immersed in much colder, still air. The wind-chill temperature expresses the temperature of still air that will provide the same rate of cooling as the moving air at a higher temperature. The factor is often misunderstood – if the air temperature is 8oC and the wind-chill temperature is 2oC, then the temperature of an object in the air will drop only to 8oC, but the rate at which the temperature drops will be faster, as if the heat were being lost to a 2oC air temperature.

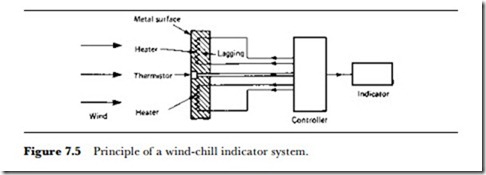

Wind-chill is easily amenable to electronic measurement, and Figure 7.5 shows one system. The thermistor measures the temperature of the sensor, which is maintained at a constant temperature by a heating element whose current is measured. In still air, the amount of current required to keep the sensor at a constant temperature will be low, because the loss is compara- tively low. In moving air, considerably more current is required to maintain the temperature constant, and this change of current is a measure of the wind-chill factor. A more practical arrangement uses one sensor in the moving air and one kept in still air at the same air temperature, comparing the current readings so as to indicate the wind-chill. Calibration is needed, and this can be done by taking readings for several values of temperature difference between the sensors.