Audio as Data

The most exciting aspects of digital technology are the tremendous possibilities that were not available with analog technology. Many processes that are difficult or impossible in the analog domain are straightforward in the digital domain. Once audio is in the digital domain, it becomes data, and only differs from generic data in that it needs to be reproduced with a certain time base.

The worlds of digital audio, digital video, communication, and computation are closely related, and that is where the real potential lies. The time when audio was a specialist subject that could evolve in isolation from other disciplines has gone. Audio has now become a branch of information technology (IT); a fact that is reflected in the approach of this book.

Systems and techniques developed in other industries for other purposes can be used to store, process, and transmit audio, video, or both at once. IT equipment is available at low cost because the volume of production is far greater than that of professional audiovisual equipment. Disk drives and memories developed for computers can be put to use in such products. Communications networks developed to handle data can happily carry audiovisual data over indefinite distances without quality loss.

As the power of processors increases, it becomes possible to perform under software control processes that previously required dedicated hardware. This allows a dramatic reduction in hardware cost. Inevitably the very nature of audiovisual equipment and the ways in which it is used is changing along with the manufacturers who supply it. The computer industry is competing with traditional manufacturers, using the economics of mass production.

Tape is a linear medium and it is necessary to wait for the tape to wind to a desired part of the recording. In contrast, the head of a hard disk drive can access any stored data in milliseconds. This is known in computers as direct access and in audio production as nonlinear access. As a result, the nonlinear editing workstation based on hard drives has eclipsed the use of tape for editing.

Digital broadcasting uses coding techniques to eliminate the interference, fading, and multipath reception problems of analog broadcasting. At the same time, more efficient use is made of available bandwidth. The hard drive-based consumer audio recorder gives the consumer more power.

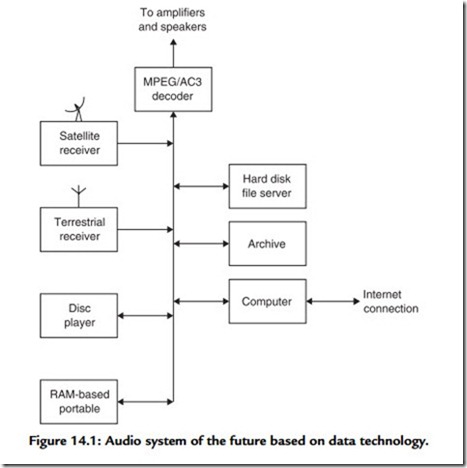

Figure 14.1 shows what the home audio system of the future may look like.

MPEG-compressed signals may arrive in real time by terrestrial or satellite broadcast, via

the Internet, or as the soundtrack of media such as DVD. Media such as compact disc supply uncompressed data for higher quality. The heart of the system is a hard drive-based server. This can be used to time shift broadcast programs, to skip commercial breaks, or to assemble requested audio material transmitted in nonreal time at low bit rates. If equipped with a Web browser, the server may explore the Web looking for material that is of the same kind the user normally wants. As the cost of storage falls, the server may download this material speculatively.

For portable use, the user may download compressed audio files into memory-based devices, which act as audio players, yet have no moving parts. On playback the bit stream is recovered from memory, decoded, and converted typically to a signal that can drive headphones.

Ultimately, digital technology will change the nature of broadcasting out of recognition. Once the viewer has nonlinear storage technology and electronic program guides, the traditional broadcaster’s transmitted schedule is irrelevant. Increasingly, consumers will be able to choose what is played and when, rather than the broadcaster deciding for them. The broadcasting of conventional commercials will cease to be effective when viewers have the technology to skip them. Anyone with a Web site that can stream audio data can become a broadcaster.