Interpretation of the Barometric Formula

We discuss the barometric formula (17.16) in the context of the competition between energy and entropy, where the temperature is the deciding factor.

The barometric formula is quite interesting as a rough indicator on the behavior of planetary atmospheres. For an exact discussion, however, one should account for temperature variances within the atmosphere, and for the spherical geometry of the planets.

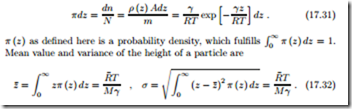

We consider a column of atmosphere of base area A. The number of moles in a layer of the atmosphere at height z is dn = ρ(z) Adz, while the total number of moles in the column is N = m/M , with m = ρAdz being the total mass in the column. The probability to find a particle in the layer at z is given by

For large values of z¯ and σ, gases are more likely to escape a planet. Obviously, z¯ and σ grow with temperature, which explains why hot planets, e.g., Mercury, have lost their atmosphere. Moreover, z¯ and σ are smaller for larger gravitation γ, which explains why heavier planets have more stable atmospheres: Jupiter, for instance, is a heavy gas planet. Finally, z¯ and σ grow with decreasing molar mass M which explains why light elements are more likely to escape from the atmosphere of a planet. Indeed, there is only little helium left in Earth’s atmosphere, although helium is one of the most abundant elements in the universe. A good source for helium is natural gas which was formed long ago, when Earth’s atmosphere was richer in helium.

The above discussion can be seen in the context of competition between energy and entropy. When the temperature is low, the entropy is less important, and the equilibrium state has a low potential energy, z¯ is small, and z¯ = 0 for T = 0. But when the temperature is high, entropy is more important, and tries to establish a state of even distribution within the accessible volume. The actual state, with exponential decay, is a compromise between the two opposing tendencies. We shall explore this competition more as we proceed.