OZONE-DEPLETING REFRIGERANTS

In 1987 the Montreal Protocol, an international environmental agreement, established requirements that began the worldwide phaseout of ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons. These requirements were later modified, leading to the phaseout, in 1996, of CFC production in all developed nations. In 1992 an amendment to the Montreal Protocol established a schedule for the phaseout of HCFCs (hydrochlorofluorocarbons).

HCFCs are substantially less damaging to the ozone layer than CFCs. However, they still contain ozone- destroying chlorine. The Montreal Protocol, as amended, is carried out in the U.S. through Title VI of the Clean Air Act. This act is implemented by the Environmental Protection Agency.

An HCFC known as R-22 has been the refrigerant of choice for residential heat-pump and air-conditioning systems for more than four decades. Unfortunately for the environment, release of R-22 resulting from system leaks contributes to ozone depletion. In addition, the manufacture of R-22 results in a byproduct that contributes significantly to global warming.

As the manufacture of R-22 is phased out over the coming years as part of the agreement to end production of HCFCs, manufacturers of residential air-conditioning systems are beginning to offer equipment that uses ozone-friendly refrigerants. Many homeowners may be misinformed about how much longer R-22 will be available to service their central A/C systems and heat pumps. The EPA document assists consumers in deciding what to consider when purchasing a new A/C system or heat pump or repairing an existing system.

Under the terms of the Montreal Protocol, the U. S. agreed to meet certain obligations by specific dates. These will affect the residential heat-pump and air -conditioning industry.

In accordance with the terms of the protocol, the amount of all HCFCs that can be produced nationwide was to be reduced by 35 percent by January 1, 2004. In order to achieve this goal, the U.S. ceased production of HCFC-141b, the most ozone-damaging of this class of chemicals, on January 1, 2003. This production ban should greatly reduce nationwide use of HCFCs as a group and make it likely that the 2004 dead- line will have a minimal effect on R-22 supplies.

After January 1, 2010, chemical manufacturers may still produce R-22 to service existing equipment but not for use in new equipment. As a result, heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) manufacturers will only be able to use preexisting supplies of R-22 in the production of new air conditioners and heat pumps. These existing supplies will include R-22 recovered from existing equipment and recycled by li- censed reclaimers.

Use of existing refrigerant, including refrigerant that has been recovered and recycled, will be allowed be- yond January 1, 2020 to service existing systems. However, chemical manufacturers will no longer be able to produce R-22 to service existing air conditioners and heat pumps.

Implications for Consumers

What does the R-22 phase out mean for consumers? The following paragraphs are an attempt to answer this question.

The Clean Air Act does not allow any refrigerant to be vented into the atmosphere during installation, service, or retirement of equipment. Therefore, R-22 must be:

• recovered and recycled (for reuse in the same system)

• reclaimed (reprocessed to the same purity levels as new R-22)

• destroyed

After 2020 the servicing of R-22-based systems will rely on recycled refrigerants. It is expected that recla- mation and recycling will ensure that existing supplies of R-22 will last longer and be available to service a greater number of systems. As noted above, chemical manufacturers will be able to produce R-22 for use in new A/C equipment until 2010, and they can continue production of R-22 until 2020 for use in servicing that equipment. Given this schedule, the transition away from R-22 to the use of ozone-friendly refrigerants should be smooth. For the next 20 years or more, R-22 should continue to be available for all systems that require R-22 for servicing.

While consumers should be aware that prices of R-22 may increase as supplies dwindle over the next 20 or 30 years, the EPA believes that consumers are not likely to be subjected to major price increases within a short time period. Although there is no guarantee that service costs of R-22 will not increase, the lengthy phaseout period means that market conditions should not be greatly affected by the volatility and resulting refrigerant price hikes that have characterized the phaseout of R-12, the refrigerant used in automotive air- conditioning systems, which has been replaced by R-134a.

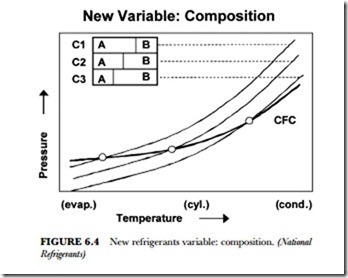

Alternatives for residential air conditioning will be needed as R-22 is gradually phased out. Non-ozone-depleting alternative refrigerants are being introduced. Under the Clean Air Act, EPA reviews alternatives to ozone-depleting substances like R-22 in order to evaluate their effects on human health and the environment. The EPA has reviewed several of these alternatives and has compiled a list of acceptable substitutes. One of these substitutes is R-410A, a blend of hydro fluorocarbon (HFC) substances that does not contribute to de- pletion of the ozone layer but, like R-22, does contribute to global warming. R-410A is manufactured and sold under various trade names, including Genetron AZ 20, SUVA 410A®, and Puron. Additional refriger- ants on the list of acceptable substitutes include R-134a and R-407C. These two refrigerants are not yet avail- able for residential applications in the U.S. but are commonly found in residential A/C systems and heat pumps in Europe. EPA will continue to review new non-ozone-depleting refrigerants as they are developed.

Existing units using R-22 can continue to be serviced with R-22. There is no EPA requirement to change or convert R-22 units for use with a non-ozone-depleting substitute refrigerant. In addition, the new substitute refrigerants cannot be used without making some changes to system components. As a result, service technicians who repair leaks will continue to charge R-22 into the system as part of that repair.

The transition away from ozone-depleting R-22 to systems that rely on replacement refrigerants like R-410A has required redesign of heat-pump and air-conditioning systems. New systems incorporate compressors and other components specially designed for use with specific replacement refrigerants. With these significant product and production process changes, testing and training must also change. Consumers should be aware that dealers of systems that use substitute refrigerants should be schooled in installation and service techniques required for use of that substitute refrigerant.

Servicing Your System

Along with prohibiting the production of ozone-depleting refrigerants, the Clean Air Act also mandates the use of common sense in handling refrigerants. By containing and using refrigerants responsibly—that is, by recovering, recycling, and reclaiming and by reducing leaks—their ozone-depletion and global-warming consequences are minimized. The Clean Air Act outlines specific refrigerant containment and management practices for HVAC manufacturers, distributors, dealers, and technicians. Properly installed home-comfort systems rarely develop refrigerant leaks, and with proper servicing a system using R-22, R-410A, or another refrigerant will minimize its impact on the environment. While EPA does not mandate repairing or replac- ing small systems because of leaks, system leaks can not only harm the environment but also result in in- creased maintenance costs.

One important thing a homeowner can do for the environment, regardless of the refrigerant used, is to select a reputable dealer that employs service technicians who are EPA-certified to handle refrigerants. Technicians often call this certification “Section 608 certification,” referring to the part of the Clean Air Act that requires minimizing releases of ozone-depleting chemicals from HVAC equipment.

Purchasing New Systems

Another important thing a homeowner can do for the environment is to purchase a highly energy-efficient system. Energy-efficient systems result in cost savings for the homeowner. Today’s best air conditioners use much less energy to produce the same amount of cooling as air conditioners made in the mid-1970s. Even if your air conditioner is only 10 years old, you may save significantly on your cooling energy costs by re- placing it with a newer, more efficient model. Products with EPA’s “Energy Star” label can save homeowners 10 to 40 percent on their heating and cooling bills every year. These products are made by most major manufacturers and have the same features as standard products but also incorporate energy saving technology. Both R-22 and R-410A systems may have the Energy Star® label. Equipment that displays the Energy Star® label must have a minimum seasonal energy efficiency ratio (SEER). The higher the SEER specification, the more efficient the equipment.

Energy efficiency, along with performance, reliability, and cost, should be considered in making a decision. And don’t forget that when purchasing a new system, you can also speed the transition away from ozone-depleting R-22 by choosing a system that uses ozone-friendly refrigerants.

Recycling Refrigerants

Several regulations have been issued under Section 608 of the Clean Air Act to govern the recycling of refrigerants in stationary systems and to end the practice of venting refrigerants to the air. These regulations also govern the handling of halon fire-extinguishing agents. A Web site and both the regulations themselves and fact sheets are available from the EPA Stratospheric Ozone Hotline at 1-800-296-1996. The handling and recycling of refrigerants used in motor-vehicle air-conditioning systems is governed under section 609 of the Clean Air Act.

In 2005 EPA finalized a rule amending the definition of refrigerant to make certain that it only includes substitutes that consist of a class I or class II ozone-depleting substance (ODS). This rule also amended the venting prohibition to make certain that it remains illegal to knowingly vent non exempt substitutes that do not consist of a class I or class II ODS, such as R-134a and R-410A.

In the same year EPA published a final rule extending the required leak-repair practices and the associated reporting and record-keeping requirements to owners and/or operators of comfort-cooling, commercial-refrigeration, or industrial-process refrigeration appliances containing more than 50 pounds of a substitute refrigerant if the substitute contains a class I or class II ozone-depleting substance (ODS). In addition, EPA defined leak rate in terms of the percentage of the appliance’s full charge that would be lost over a consecutive 12-month period if the current rate of loss were to continue over that period. EPA now requires calculation of the leak rate whenever a refrigerant is added to an appliance.

In 2004 EPA finalized a rule sustaining the Clean Air Act prohibition against venting hydrofluorocarbon (HFC) and perfluorocarbon (PFC) refrigerants. This rule makes the knowing venting of HFC and PFC refrigerants during the maintenance, service, repair, and disposal of air-conditioning and refrigeration equipment (i.e., appliances) illegal under Section 608 of the Clean Air Act. The ruling also restricts the sale of HFC refrigerants that consist of an ozone-depleting substance (ODS) to EPA-certified technicians. How- ever, HFC refrigerants and HFC refrigerant blends that do not consist of an ODS are not covered under “The Refrigerant Sales Restriction,” a brochure that documents the environmental and financial reasons to replace CFC chillers with new, energy-efficient equipment. A partnership of governments, manufacturers, NGOs (nongovernmental organizations), and others have endorsed the brochure to eliminate uncertainty and underscore the wisdom of replacing CFC chillers.

Leak Repair

The leak-repair requirements, promulgated under Section 608 of the Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990, are that when an owner or operator of an appliance that normally contains a refrigerant charge of more than 50 pounds discovers that the refrigerant is leaking at a rate that would exceed the applicable trigger rate during a 12-month period, the owner or operator must take corrective action.

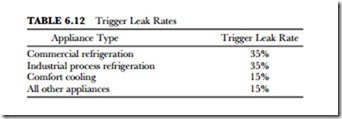

For all appliances that have a refrigerant charge of more than 50 pounds, the trigger leak rates for a 12- month period shown in Table 6.12 are applicable (see Table 6.12).

In general, owners or operators must either repair leaks within 30 days from the date the leak was discovered or develop a dated retrofit/retirement plan within 30 days and complete actions under that plan within one year from the plan’s date. However, for industrial-process refrigeration equipment and some federally owned chillers, additional time may be available.

Industrial-process refrigeration is defined as complex customized appliances used in the chemical, phar- maceutical, petrochemical, and manufacturing industries. These appliances are directly linked to the indus- trial process. This sector also includes industrial ice machines, appliances used directly in the generation of electricity, and ice rinks. If at least 50 percent of an appliance’s capacity is used in an industrial-process re- frigeration application, the appliance is considered industrial-process refrigeration equipment and the trig- ger rate is 35 percent.

Industrial-process refrigeration equipment and federally owned chillers must conduct initial and follow- up verification tests at the conclusion of any repair efforts. These tests are essential to ensure that the repairs have been successful. In cases where an industrial-process shutdown is required, a repair period of 120 days is substituted for the normal 30-day repair period. Any appliance that requires additional time may be sub- ject to record-keeping/reporting requirements.

Additional time is permitted for conducting leak repairs if the necessary repair parts are unavailable or if other applicable federal, state, or local regulations make a repair within 30 or 120 days impossible. If own-

ers or operators choose to retrofit or retire appliances, a retrofit or retirement plan must be developed within 30 days of detecting a leak rate that exceeds the trigger rates. A copy of the plan must be kept on site. The original plan must be made available to EPA upon request. Activities under the plan must be completed within 12 months from the date of the plan. If a request is made within 6 months from the expiration of the initial 30-day period, additional time beyond the 12-month period is available for owners or operators of in- dustrial-process refrigeration equipment and federally owned chillers in the following cases: EPA will per- mit additional time to the extent reasonably necessary if a delay is caused by the requirements of other ap- plicable federal, state, or local regulations or if a suitable replacement refrigerant, in accordance with the regulations promulgated under Section 612, is not available; and EPA will permit one additional 12-month period if an appliance is custom-built and the supplier of the appliance or a critical component has quoted a delivery time of more than 30 weeks from when the order was placed (assuming the order was placed in a timely manner). In some cases EPA may provide additional time beyond this extra year where a request is made by the end of the ninth month of the extra year.

The owners or operators of industrial-process refrigeration equipment or federally owned chillers may be relieved from the retrofit or repair requirements if:

• second efforts to repair the same leaks that were subject to the first repair efforts are successful

• within 180 days of the failed follow-up verification test, the owners or operators determine the leak rate is below 35 percent; in this case, the owners or operators must notify EPA as to how this determination was made and submit the information within 30 days of the failed verification test For all appliances subject to the leak-repair requirements, the timelines may be suspended if the appliance has undergone system mothballing. System mothballing means the intentional shutting down of a refrigeration appliance undertaken for an extended period of time where the refrigerant has been evacuated from the appliance or the affected isolated section of the appliance to at least atmospheric pressure. How- ever, the timelines pick up again as soon as the system is brought back online.