Condenser Water

Condenser water is water that flows through the condenser of a chiller to cool the refrigerant. Condenser water from a chiller typically leaves the chiller at 95°F and returns from the cooling tower at 85°F or cooler. The cooling tower is a device that is used for evaporative cooling of water.

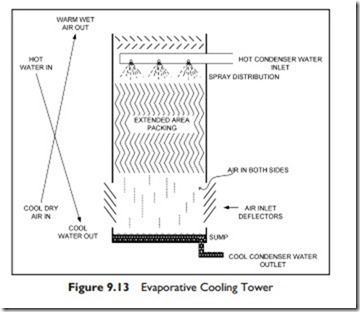

In Figure 9.13 the hot, 95°F, water from the chiller condenser flows in at the top. It is then sprayed, or dripped, over fill, before collecting in the tray at the

bottom. Air enters the lower part of the tower and rises through the tower, evaporating moisture and being cooled in the process, before exiting at the top.

We will consider cooling towers in more detail in the next chapter, but the tower has a hydraulic characteristic that we will cover here. The water has two open surfaces, the one at the top sprays and the other at the sump surface. This is an open-water system. An open-water system is one with two, or more open water surfaces. A closed-water system has only one water surface.

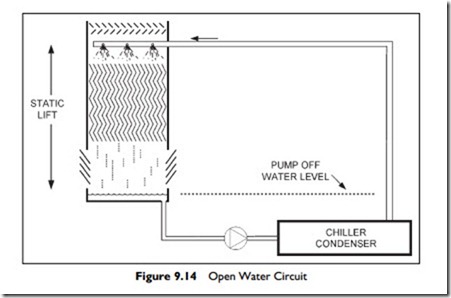

Figure 9.14 shows an outline elevation of the complete cooling tower and chiller condenser water circuit. The water loop has two water surfaces, one at the top water sprays and one below at the sump water surface. When the pump is “off,” the water will drain down to an equal level in the tower sump and in the pipe riser, as indicated by the horizontal dotted line in Figure 9.14. When the pump starts, it first has to lift the water up the vertical pipe before it can circu- late it. The distance that the pump has to lift the water is called the “static lift.” Once running, the pump has to provide the power to overcome both the static lift and the head, to overcome friction, to maintain the water flow.

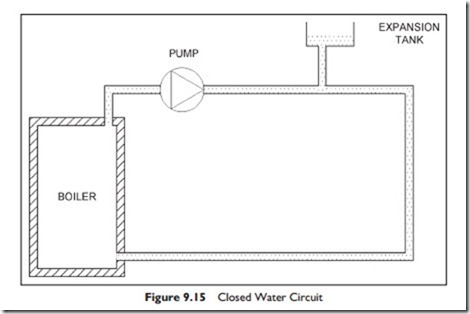

Figure 9.15 shows a closed water circuit. It is shown with one water surface open to the atmosphere. Whether the pump runs or not, the water level stays constant. When the pump starts, it only has to overcome friction to establish and maintain the water flow. When the pump stops, the flow stops, but there is no change in the water level in the tank. The open surface is required to allow for expansion and contraction as the water temperature changes during operation. In larger systems and most North American systems, the one open water surface is in a closed tank of compressed air rather than open to atmosphere, as is common in other parts of the world.

The cooling tower provides maintenance challenges. It contains warm water and dust, so it easily supports the multiplication of the potentially lethal bacteria, legionella.

We will return to cooling towers, their design, interconnection and operation when we discus central plants in the next chapter.

The Next Step

This chapter has covered hydronics architecture, specifically the piping systems for steam, hot water, chilled water and condenser water. In Chapter 10 we are going to consider the central plant boilers, chillers and cooling towers that produce the sources of steam and water at various temperatures.