Role of Nuclear Energy in the European Generation Electricity

The major reduction in the use of nuclear energy for electricity production is expected to occur in the European region, dropping from 29.5 % in 2005 to 12 % in 2030,5 if no actions to stop this tendency is adopted by the European governments that are now using nuclear energy for electricity production or are thinking to introduce the use of this type of energy source for this purpose in the near future. The foreseeable reduction in the use of nuclear energy for electricity production in the European region in the coming years is expected to be from 170 to 74 GWe. This reduction represents 56.4 % of the region current total electricity production.

There are two main reasons why some European governments have distanced themselves in the past from the use of nuclear energy for electricity generation. One is political; the second is social. However, it is interesting to note the consequences of the inertia policy adopted by the nuclear industry, allowing governments to adopt positions, which are evidently not defensible in the long term from the economic point of view. A clear example of this position is the following: Some European governments adopted an energy policy to phase-out the use of nuclear energy for electricity generation without any coherent strategy for the replacement of this type of energy. Such a position has only been possible because nuclear phase-out policy has largely meant retaining nuclear power plants until their operational lifetimes are expired; very little capacity has so far actually been lost.

The approaching imminence of the closure of old nuclear power reactors and the realization that Europe’s Kyoto Protocol obligations are looking increasingly difficult to meet are some of the reasons why there are now signs that some European governments are starting to reconsider their position toward the use of nuclear energy for electricity generation. The long timescales required for the deployment of new nuclear power reactors mean that the options for responding to changing demands are very limited. Some politicians would prefer to defer deci- sions of Europe’s nuclear future until renewables have been given an opportunity to deliver. Unfortunately, by the time this becomes clear, it may well be too late to obtain the fullest advantage of nuclear generation. Even if renewables probe able to meet their target in Europe, they would barely match the contribution that nuclear energy is already making at present and further carbon savings will be needed. Faced with the extreme dangers of global climate change, the only sensible strategy is to keep the nuclear option open.

In the EU, the energy demand in 2002 was covered with oil at 41 %, by gas at 22 %, by coal at 16 % (hard coal, lignite, and peat), by nuclear power at 15 %, and by renewables at 6 %. In 2005, the EU-27 satisfied its primary energy consumption with oil at 36.7 %, gas at 24.6 %, coal at 17.7 %, nuclear at 14.2 %, renewables at 6.7 %, and industrial waste at 0.1 %. If nothing is done by the EU governments in the coming years, then it is expected that the total energy picture in 2030 will continue to be dominated by fossil fuels: 38 % by oil, 29 % by gas, and 19 % by solid fuels. Renewables will be 8 % and nuclear power only by 5.2 %, this means a reduction in the nuclear share of 9 % with respect to 2005.

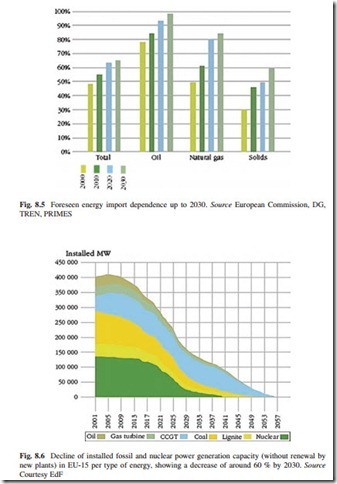

The foreseen energy import dependence in the EU up to 2030 is shown in Fig. 8.5. The electricity generating mix of the future must take into account, among other elements, the different economic, ecological, social, and entrepreneurial interests that could exist within countries, putting aside any ideological factor. All available energy sources and technologies must be evaluated and meaningfully combined following due consideration of their advantages and disadvantages, their accessibility and level of reserves, their potential macroeconomic benefits, as well as the impact on the environment, among others. It is important to highlight that the three main central goals of any energy policy and of the energy industry are always the following:

• Supply reliability;

• Cost efficiency;

• Environmental soundness.

Figure 8.6 shows the foreseeable decline of installed fossil and nuclear power gen- eration capacity (without renewal by new plants) in the EU-15 per type of energy.

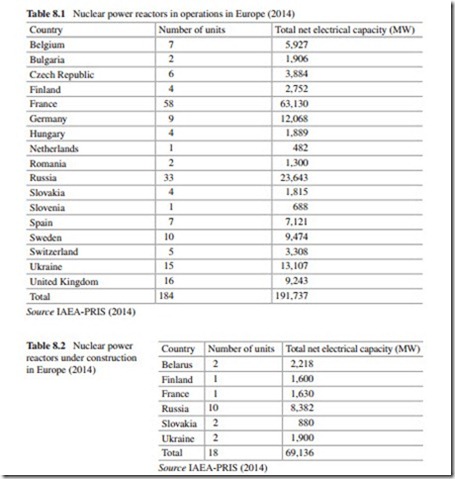

In Tables 8.1 and 8.2, the number of nuclear power reactors in operation and the number of new units under construction by country in the European region are included.

According to the latest IAEA’s information, the European region6 has 184 operating nuclear power plants in 17 countries and 18 new units under construction in six countries. Overall, the nuclear power reactors in operation have a net capacity of 191,737 MW. The 18 nuclear power reactors under construction will add 69,136 MW to the existing capacity (see Table 8.2).

In Western Europe, capacity has remained relatively constant despite recent nuclear phase-out laws adopted in Belgium, Germany, and Sweden, as well as the closure of old nuclear power reactors carried out in Germany and in some other countries. The most advanced programs for the construction of new nuclear power capacity in Western Europe are located in Finland and France, which are con- structing two new reactors of third generation (EPR system). In Eastern Europe, only Slovakia has two nuclear power reactors under construction, but some other countries, such as Romania, the Czech Republic, Poland, and Bulgaria, are planning to resume or start the construction of new units in the near future.

The cut of the supply of Russian gas to Europe due to the dispute of prices with Ukraine in the last years has revived the interest in the use of nuclear energy for electricity generation and heating in several European countries, in order to reduce their energy dependence of Moscow. Slovakia and Bulgaria have announced their intention to restart the operation of old nuclear power reactors of Soviet design that were closed as previous condition for the entrance of these two countries to the EU due to shortest in the generation of electricity. These announcements have provoked a strong reaction from the EC. The EU organ has declared openly that the reopen- ing of these units would be illegal since the pact of adhesion to the EU requires the closing and dismantlement of them. It is important to single out that the closure of the nuclear power reactors in Slovakia has reduced significantly the contribution of nuclear energy to the electrical system of the country from 60.8 to 42 %. In the case of Bulgaria, the nuclear contribution has decreased from 42 to 34 %. Both countries with the closing of the old soviet design units have passed of being energy exporters to become energy importers, and this situation has a negative impact on their economies. As for the other countries of the Eastern Europe, Hungary does have plans for the construction of new nuclear power reactors, and has prolonged 20 years the useful life of its four units currently in operation, while Rumania that has two nuclear power reactors in operation is taking steps to build two new units in the coming years. The Czech Republic has placed nuclear energy as one of the priorities within its energy development plan for the future and Poland continue the preparation for the introduction of a nuclear power program in the future.

On the other hand, the Russian Federation continues its program to extend licenses at 11 nuclear power reactors now in operation and for the construction of ten new units in the coming years with the purpose to add 8,382 MW to its electrical system. Ukraine, despite of the consequences of the Chernobyl nuclear accident, has two nuclear power reactors under construction with the purpose of adding 1,900 MW to the electrical system.

Considering Europe as a whole, it is easy to reach the conclusion that France is the country with the highest number of nuclear power reactors in operation (58 units). Other countries with an important number of nuclear power reactors in operation in the European region are the following: The Russian Federation (33 units), UK (16 units), Ukraine (15 units), Sweden (10 units), and Germany (9 units).

It is expected that during the next two decades, the European region might need between 200 and 300 GWe of new generating capacity. Replacement of the existing energy infrastructure could double this amount. The main question to be answered is the following: How to satisfy this foreseeable increase in the demand of energy in the European region without increasing the emission of CO2, as well as other gas of greenhouse effect in the atmosphere? To satisfy the foreseeable increase in the energy demand in the Europe region in the coming years could be a very difficult goal to be achieved, if the European countries decided to use mainly renewable energy sources to reduce the emission of CO2, as well as other gas of the greenhouse effect, and if nuclear energy is excluded from the energy mix. Has been demonstrated that the use of nuclear energy for electricity generation is environmentally clean that the safety of the nuclear power reactors is very high and there is a safe and proven technology available for the disposal of the high-level nuclear waste produced by the operation of these reactors.

Finally, it is important to highlight that energy saving is an important element to reduce the consumption of energy in the European region, but cannot alone make a significant contribution to the required extend, in spite of some estimation that 18 % of the energy use could be saved using available technologies. The total estimated energy waste is the equivalent of the total energy needs of Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands, Finland, and Greece combined.