Sweden

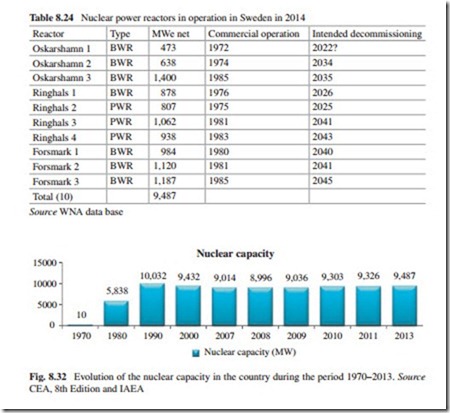

According to Morales Pedraza (2012), Sweden was the first of the Scandinavian countries to have a commercial nuclear power plant. The construction work of the first unit, with a net capacity of 467 MWe, started in August 1966 (Oskarshamn 1).21 In 2104, Sweden has ten nuclear power reactors in operation with a net capacity of 9,487 MWe (see Table 8.24).

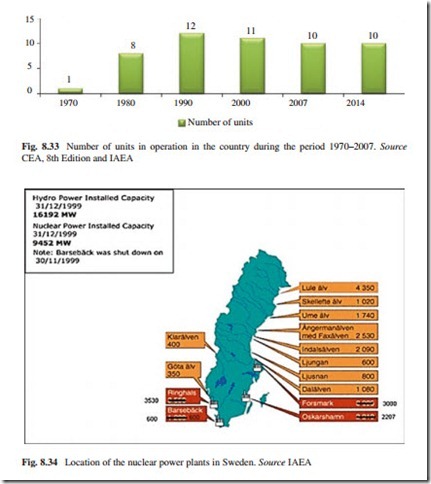

The evolution of the nuclear capacity in the country and the evolution of the number of nuclear power reactors operating in the country during the period 1970–2014 are shown in Figs. 8.32 and 8.33.

From Fig. 8.32, the following can be stated: The nuclear capacity of the coun- try during the period 2000–2013, increased very little (0.6 %). This means that no new capacity was installed in the country during that period. It is expected that the nuclear capacity of the country will decrease in the coming years as a result of the implementation of the nuclear phase-out policy adopted by the government.

The location of all nuclear power reactors in Sweden is shown in Fig. 8.34. Sweden’s energy requirement is covered both by imported energy, primarily oil, coal, natural gas, and nuclear fuel, and by domestic energy in the form of hydropower, wood, and peat plus waste products from the forestry industry (bark and liquors). Originally, all energy was domestic, primarily wood and hydropower. However, during the nineteenth century, coal began to be imported and came to play an important role until the beginning of World War II, when oil and hydropower together became the base of the energy supply (Sweden-IAEA Country File 2003).

The Energy Policy in Sweden

According to the IAEA Sweden country file, in both the long and the short term, the objective of Swedish energy policy is to ensure reliable supplies of electricity and other forms of energy to carriers at prices that are competitive with those of other countries. It is intended to create the right conditions for cost-efficient Swedish energy supply and efficient energy use, with minimum adverse effects on health, the environment or the climate. The Swedish government also promotes the concept of an eco-efficient economy, strongly advocating energy efficiency, green energy and low-carbon technologies as positive drivers, not costs, for welfare and growth.

In the spring of 2009, the Swedish government presented a new comprehensive energy and climate policy, which was approved by parliament in June 2009. This integrated energy and climate policy is strongly influenced by the common EU policies in those same areas. In several instances, the Swedish policies are more ambitious than the targets set by the EU. For example, targets for 2020 include a 40 % reduction (compared to 1990 levels) of greenhouse gas emissions in the non- ETS sector (which is more ambitious than the EU target for Sweden, of a decrease of 17 % compared to 2005 levels), 50 % renewable energy (EU obligation: 49 %), 20 % higher energy efficiency, and 10 % renewable energy in the transport sector (common binding EU target). In addition, the EU has called for the transport sec- tor to reduce its emissions by 21 % by 2020. The overall EU target for climate gas emission reductions is 20 % by 2020, and the EU has committed to a reduction of 30 % if other industrialized countries/regions adopt goals of a similar magnitude.

In addition to these medium-term goals, the Swedish government has set the goal for a vehicle stock that is “independent” of fossil fuels by the year 2030 and aimed for fossil fuels to have been totally removed from the heating sector by 2020, with visions that Swedish net-emissions might reach zero by 2050.

Operationally, these visions, goals, and targets have been translated into three action plans that are further developed by responsible authorities (e.g., the Swedish Energy Agency and the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency):

• An action plan for renewable energy, which includes an increase in the ambitions within the electricity certificate system to a level of approximately 25 TWh of new renewable electricity by 2020 and introduces increased ambitions when it comes to finding suitable locations for wind power—meaning that local governments should have the readiness to introduce a total of 20 TWh wind power onshore and 10 TWh wind power offshore. Sweden and Norway have operated a joint electricity certificate market since the beginning of 2012. Renewable electricity production that is approved by the system receives electricity certificates that can be used in both countries. The target of the joint electricity certificate market is to increase renewable electricity production by 26.4 TWh between 2012 and 2020;

• An action plan for energy efficiency, primarily by raising awareness, but also by introducing energy efficiency programs targeted toward the industry and service sector companies. Heavy industry is already taking part in a voluntary agreement program as well as, in most cases, the EU-ETS system;

• An action plan for a vehicle fleet independent of fossil fuels, where economic incentives will play the major role, e.g., CO2 taxes penalizing the use of fossil fuels and tax rebates for environmentally friendly vehicles.

The government also stresses the importance of efficient energy markets and pro- motes the further development of common electricity and gas markets, both in the North European and the pan-European context.

Finally, it is important to highlight that for the time being nuclear power will continue to play an important role in the Swedish energy system. However, the future of nuclear power in Sweden is difficult to predict, because the new government has decided to implement a nuclear phase-out policy with the aim of closing all nuclear power reactors in the coming decades.

The Phase-out Policy

The Swedish Energy Policy was affected by the Three Mile Island nuclear accident in the USA. As a consequence of this accident, the Swedish government adopted a decision “to call a public referendum in Sweden, to remove the issue from the election campaign late in 1979. The 1980 referendum canvassed three options for phasing out nuclear energy, but none for maintaining it. A clear major- ity of voters favored running the existing nuclear power plants and those under construction as long as they contributed economically in effect to the end of their normal operating lives (assumed then to be 25 years)” (IAEA 1987). It is important to highlight that the Swedish parliament decided to embargo further expansion of the use of nuclear energy for the production of electricity in the county in the future and to start the decommissioning of the ten nuclear power reactors currently under operation by 2010, if new energy sources were available and can replace them technically and economically. The use of this new type of energy source should be also an acceptable alternative from the environmental point of view.

In addition to the Three Mile Island nuclear accident, the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, which was initially detected at a Swedish nuclear power plant, created additional pressure on the Swedish government to shutdown all nuclear power reactors operating in the country. In 1988, the government decided to begin in 1995 the phase-out of all nuclear power reactors, but this decision was overturned in 1991 due to the strong opposition of the trade unions to implement it. Three years later, the government appointed an Energy Commission consisting principally of backbench politicians, which reported at the end of 1995 that a complete phase-out of nuclear power by 2010 would be economically and environmentally impossible. However, it said that one unit might be shutdown by 1998. This gave rise to intense political maneuvering among the main political parties, all of them minority, with varied attitudes to industrial, nuclear, and environmental issues. The Social Democrats ruled a minority government, but with any one of the other parties they were able to get a majority in parliament. Early in 1997, an agreement was forged between the Social Democrats and two of the other par- ties, which resulted in a decision to close Barseback Units 1 and 2, both 600 MWe BWRs constructed by ASEA-Atom and commissioned in 1975 and 1977, respectively. They were closed in 1999 and 2005, respectively. The positive aspect of the decision to close Barseback Units 1 and 2 is that the other nuclear power reactors gained a reprieve beyond 2010 and will be able to run for about 40 years, this means during the period 2012–2025 (Sweden WANO 2008).

It is important to note that due to uncertainties about energy prices and the security of energy supply, in 1965 a decision was adopted by the Sweden government to supplement the production of electricity using nuclear energy. Today, most of Sweden’s electricity is produced by the following three types of energy: (a) Hydropower; (b) Nuclear power; and (c) Conventional thermal power plants, but in this last case accounting for only about 5 %. Oil-fired cold condensing power plants and gas turbines are used today, primarily, as reserve capacity during dry years due to low precipitation.

Electricity Generation Using Nuclear Energy

Sweden was the first country in the world in penalizing the use of nuclear energy for the production of electricity. According to the Financing Act on Nuclear Activities from 1981, the nuclear utilities have to pay a fee per produced kW/h to a state fund. The fund shall cover all future costs for handling and final storage of all waste and for decommissioning of all nuclear facilities. In the late 1990s, the Sweden’s government imposed a capacity tax on nuclear power at SEK 5,514 per MW thermal per month (€0.30– €0.32 cents) potentially produced. In January 2006, the tax was almost doubled to SEK 10,200 per MWt (about €0.6 cents/kWh). In 2007, it was proposed to increase it further to SEK 12,684 per MWt from 2008—total SEK 4 billion (€435 million, meaning about €0.67 per kWh) (Sweden WANO 2008).

Why the uses of nuclear energy for the production of electricity expand so fast in Sweden after the Second World War? The reason was a yearly increase in the power consumption of 7 % during several years and the impossibility to satisfy this increase using hydropower. Neither the Sweden’s government nor the utilities wanted to use oil-fired power plants to satisfy this increase because this will increase further the dependence on oil imports. For this reason, the only available option that the Sweden’s government had at that time in their hands to increase the electricity generation and satisfy the demand of energy was the use of nuclear energy for this purpose.

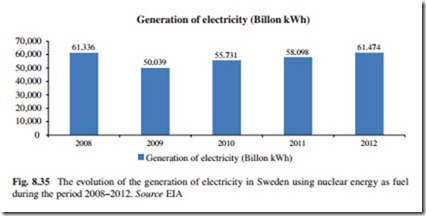

However, just before the general election in 1976, nuclear power became a main political matter due the nuclear waste issue. The leader of the Centre Party became Prime Minister with the government consisting of a non-socialistic coalition. The new government arranged a huge investigation into the risks and economies of nuclear power compared to other energy sources in an official Ad hoc Energy Commission. In 1977, a unique act about the nuclear waste was accepted by the Sweden parliament. The new waste act, called the “Stipulation Act of 1977,” includes the conditions to be met by the proprietor of a nuclear power reac- tor before it can start operating. According to this act, the utilities would not be allowed to load fuel into a new nuclear power reactor (and several were in the pipeline) before it had been shown that it was possible to arrange a final storage of the waste in an absolutely safe way. Before parliament accepted the act, a remark was added in the minutes saying that the word “absolutely” should not be inter- preted in a “draconian” way (Sweden-IAEA Country File 2003) The evolution of the generation of electricity in Sweden using nuclear energy as fuel during the period 2008–2012 is shown in Fig. 8.35.

According to Fig. 8.35, the generation of electricity using nuclear energy as fuel in Sweden during the period 2008–2012 increased very little (0.2 %). It is expected that the participation of nuclear energy in the energy mix of the coun- try will decrease in the coming decades as a result of the implementation of the nuclear phase-out policy adopted by the government, unless a decision is taken by the government and the parliament reversing this policy.

The Public Opinion

A week after the Three Miles Island nuclear accident, all the political parties agreed to arrange a referendum about the future of nuclear power in Sweden. A special law was adopted forbidding the start of the operation of all new nuclear power reactors until the referendum is carried out. The referendum was carried out in March 1980 and some months later the Sweden’s parliament decided, in accord- ance with the result of the referendum, “to allow the start of the operation of all the nuclear power reactors, which were ready to operate or the continuation of the construction of the new nuclear power reactors.” It was also decided “that nuclear power would be phased out by 2010, if new energy sources were available at that time and could be introduced in such a way that it would not affect the social welfare program and the employment in the heavy industry.”

The Chernobyl nuclear accident resulted in a new political debate about the future of the Swedish nuclear power program. Sweden’s parliament decided, in 1988, “that the phase-out of nuclear power reactors would start within the period 1995–1996, with two units to be closed.” However, after the decision to phase-out nuclear power plants in the country, the industry and the labor unions started an intensive debate, based on official reports prepared by the government, singling out that the total cost of an early phasing out (after 25 years operation instead of 40 years, which is the assumed technical lifetime of the Swedish nuclear power reactors) would cost the society more than SEK 200 billion. The price of energy for the electricity-intensive industry (paper and steel) would double and this increase in the energy price will force an estimate between 50,000 and 100,000 persons to lose their jobs. Based on this estimate, the Sweden’s parliament decided, in 1991, not to start the phase-out of nuclear power reactors by 1995.

Taking into account that, in 2007, nuclear power accounts for 46 % of the total electricity produced in Sweden, the shutdowns of all nuclear power plants could trigger record price increases in almost all sectors of the Sweden’s economy. However, the Swedish government energy agency said “the nation’s electricity supply was not currently at great risk because it can rely more on hydropower during the summer months.” For many experts, this is a very optimistic statement.

It is important to highlight that in the past four years, and in the light of concerns about climate change, the public opinion in Sweden adopted a more positive attitude in favor of the use of nuclear energy for electricity generation. In April 2004, total of 17 % supported a nuclear phase-out, 27 % favored continued operation of all the country’s nuclear power plants, 32 % favored this plus their replacement in due course, and 21 % wanted to further develop nuclear power in Sweden. The total support for main- taining or increasing nuclear power thus was 80 % as the government tried to negotiate a phase-out acceptable solution. This total support had risen to 83 % in March 2005, with a similar proportion saying that limiting greenhouse gas emissions should be the top environmental priority. With slightly different questions, total support for maintaining or developing nuclear power was 79 % in June 2006 and fluctuated around this level to November 2007 when it was 77 %. A self-assessed 18 % (26 % of men and 11 % of women) said, on November 2007, that they had become more positive toward nuclear power in the light of concerns about climate change, while 7 % (4 % of men and 10 % of women) said that they had become more negative. This may be related to 14 % who thought that nuclear power was a source of CO2 with a large impact on the environment (8 % of men and 21 % of women) (Sweden-WANO 2008).

By February 2010, however, the positive opinion had diminished. A poll (number of respondents, 1,500) on behalf of the country’s electricity-intensive industries showed 30 % support for replacement of the current fleet of nuclear power reactors as they reach the end of operating lives, plus 22 % who also favored building new units in the future. Some 45 % preferred a phase-out of nuclear energy. However, when asked which source of energy is best for both employment and climate, nuclear energy was the most popular answer, with 26 %, followed by wind (21 %), hydro (18 %), solar (14 %), and biofuels (12 %) (Sweden World Nuclear News, March 17, 2010).

In late June 2010, a survey (number of respondents, 1,008) commissioned by the Liberal Party was reported to show overall 72 % support for the government decision to allow the building of new nuclear power reactors, with 28 % opposed (The Local, Sweden, July 10, 2010). Even among Social Democrats, who have threatened to reverse the decision if elected later in 2010, 66 % of supporters were in favor of the construction of new nuclear power reactors in the future.

In May 2011, immediately after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, a Novus poll (number of respondents, 1,000) showed 33 % support for continuing to use nuclear power and replace existing reactors, 36 % for continuing to use existing reactors, and 24 % wanting to phase-out by political edict. In August 2010, there had been 40 % support for the use of nuclear energy for electricity generation and to replace old units for new ones and only 19 % for the implementation of the phase-out policy.

In May 2013, the same Novus poll showed 38 % support for continuing to use nuclear power and to replace existing units, 30 % for continuing to use existing reactors, and 21 % wanting to the implementation of the phase-out policy. This changed little to October 2013, with figures 35, 33, and 22 %, respectively. The series of Novus polls since 2010 show men much more positive than women to the use of nuclear energy for electricity generation, typically over 75 % compared with about 60 % for women.

Looking Forward

According to Morales Pedraza (2012), after the early closure of Barseback-1 and 2, the government is working with the utilities to expand nuclear capacity to replace the 1,200 MWe lost. The actions adopted are the following:

• Ringhals 3 was subject to a major uprate. Steam generator was replaced in 2007. Early in 2008, it was operating at 985 MWe net, which is a little less than anticipated, but a further 5 % uprate is expected in the coming months;

• The older BWR Unit 1, a 15 MWe uprate was completed in 2007, with another 15 MWe to follow in the future;

• Ringhals 4 had a 30 MWe uprate to 935 MWe following the replacement of its low-pressure turbines in 2007. Exchange of high-pressure turbines and steam generators in 2011 and other work to be carried out in this unit in the future is expected to yield a further 240 MWe. The total uprate for the Ringhals nuclear power plant is likely to be more than 400 MWe costing €225 million to be car- ried out during the period 2008–2010. In 2004, low-pressure turbines were replaced in Unit 3 of the Ringhals nuclear power plant, giving a 30 MWe uprate. The same is being done for Units 1 and 2.

In 2005, Sweden authorities approved an uprate of the Oskarshamn 3 Unit to 1,450 MWe net and this was confirmed by the government in January 2006. The US$450 million project involves the turbine upgrade in 2008, as well as a reac- tor upgrade. These modifications will extend the nuclear power plant’s life up to 60 years. It is important to highlight that the operation of the unit has been author- ized only for a period of one year, when the unit will be stopped for refueling. At that moment, the owner of the nuclear power plant should request another authori- zation to operate the unit definitively.

Regarding the future of the nuclear power program in Sweden, it is important to highlight the following. In February 2009, the Swedish government announced his intention of annulling the prohibition that was imposed in 1980s to build more nuclear power reactors or to prolong the life of those already in operation. In the past years, through their state electricity company, Vattenfall, the government had followed an intelligent policy that combined strategic vision of acquiring an external power capac- ity with a commercial orientation that took to the company to acquire important generation assets in the North of Europe. The use of renewable energy sources for electricity generation was promoted by the government as well as a reduction of the CO2 emissions to the atmosphere and an increase in the security supply of energy.

The Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt took the decision that the current nuclear power reactors in operation should be substituted by new ones and to consider the possibilities to construct new nuclear power reactors in the future, if necessary. The decision was adopted taking into account first recent problems of gas sup- ply in the Baltic states due to the dispute between Russia and Ukraine that put in evidence the strong energy dependence of the whole region, and second due to the wish of Sweden to be a world leader in the reduction of emissions of polluting gas emissions to the atmosphere.

Without any doubt, Sweden is one of the countries with more sensibility for the nature, and its environmental politicians are a reference for environmentalist groups. The Swedish decision of 1980s prohibiting the construction of nuclear power plant was exhibited by these groups as a model to follow by other countries. Thirty years later, the conservative coalition that is in power in the country rectifies this decision and affirms that the nuclear power reactors in operation should be replaced by new units with the purpose of reducing the emissions of polluting gases and fulfill the commitments of and obligations adopted by the Sweden’s government with the Kyoto Protocol.

Finally, it is important to highlight the following. After the elections carried out in mid-2014, the junior coalition Green Party in the new government persuaded its Social Democrat partner to set up an energy commission charged with the phasing out of nuclear power in the country. Social Democrat leader Stefan Lofven had earlier said that nuclear power would be needed for “the foreseeable future,” though the Greens campaigned to have two of Sweden’s reactors closed in the next four years. The Social Democrats got 31 % of the vote in the election and the Greens 7 %. Public opinion polls in the past few years had shown a steady majority (over two-thirds) support for nuclear power.

The two parties said in separate, but identical statements that nuclear power should be replaced with renewable energy and energy efficiency. The goal, they said, should be at least 30 TWh per year of electricity from non-hydro renewable energy sources by 2020, compared with about 18 TWh per year now. The two parties said that nuclear power “should bear a greater share of its economic cost,” despite Sweden’s unique high tax specifically on nuclear power (about €0.67 cents per kWh) already, and waste management being fully factored into running costs at €0.24 cents per kWh.

In addition, there is also an important element that needs to be taken into account. This element is the following: Sweden, the country with the highest number of public companies in Europe, will adopt the Finnish position on nuclear matters, that is to say, the construction of new nuclear power reactors should be a private initiative promoted by the big industrial consumers. In other words, the Sweden’s government will not subsidize the construction of new nuclear power reactors in the future and this is something that could make more difficult the construction of these types of power reactors in the country in the future.

Sweden’s nuclear power plant operators have until the end of 2015 to submit plans to the country’s regulator on implementing permanent safety improvements by 2020 to ensure independent reactor core cooling.

In October, the Swedish Radiation Safety Authority (SSM) announced a two- stage set of upgrades it wants to see at the country’s ten operating nuclear power reactors. By 2017, all reactors should have independent systems to ensure power and water is available for emergency cooling for a period of 72 h. This is in common with post-Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident upgrades undertaken in many countries, and already in progress in Sweden under the power plant operators’ own initiative. SSM said this requirement could be met by means such as mobile diesel generators and external water storage.

By 2020, SSM wants the nuclear power plants to have a “robust permanent installation that includes power supply and systems for pumping of water and an external water source independent of those used in existing emergency cooling systems. This is significantly more complicated, requiring engineering deep within the reactor building and potentially its primary coolant circuit.

SSM has now said that power companies must submit an implementation plan by the end of June 2015 for the temporary measures to be implemented by 2017. They must also submit a plan by the end of 2015 for implementing the permanent measures required by 2020.

The regulator noted that for those reactors that utilities plan to retire in the few years that follow 2020, the power companies can apply for a modification of the conditions of the requirements to install a system of independent core cooling.”

Oskarshamn 1 as well as Ringhals 1 and 2 is slated to close between 2022 and 2026, while the country’s seven other units are expected to close between 2034 and 2045. The Director of SSM’s nuclear safety department Michael Knochenhauer said, “We are now raising the requirements for all reactors. Independent core cooling reduces the risk of meltdown in an accident and that of a major radioactive release to occur.”