Most small diesel engines are fitted with an electric starter, battery, and generator. The circuit might include glow plugs for cold starting and electrically operated instruments such as pyrometers and flow meters. The diesel technician should have knowledge of electricity.

This knowledge cannot be gleaned from the hardware just looking at an alternator will not tell you much about its workings. The only way to become even remotely competent in electrical work is to have some knowledge of basic theory. This chapter is a brief, almost entirely nonmathematical, discussion of the theory.

Atoms are the building blocks of all matter. These atoms are widely distributed; if we enlarged the scale to make atoms the size of pinheads, there would be approx- imately one atom per cubic yard of nothingness. But as tiny and as few as they are, atoms (or molecules, which are atoms in combination) are responsible for the char- acteristics of matter. The density of a substance, its chemical stability, thermal and electrical conductivity, color, hardness, and all its other characteristics are fixed by the atomic structure.

The atom is composed of numerous subatomic particles. Using high-energy dis- integration techniques, scientists are discovering new particles almost on an annual basis. Some are reverse images of the others; some exist for only a few millionths of a second. But, we are only interested in the relatively gross particles whose behavior has been reasonably well understood for generations.

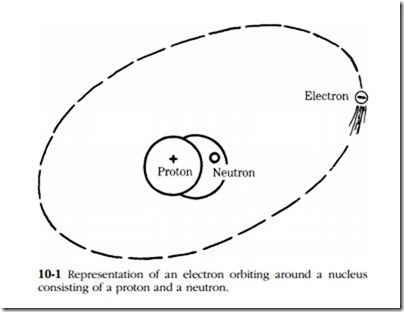

In broad terms the atom consists of a nucleus and one or more electrons in orbit around it. The nucleus has at least one positively charged proton and might have one or more electrically neutral neutrons. These particles make up most of the atom’s mass. The orbiting electrons have a negative charge. All electrons, as far as we know, are identical. All have the same electrical potency. Their orbits are balanced by centripetal force and the pull of the positive charge of the nucleus (Fig. 10-1).

A fundamental electrical law states unlike charges attract, like charges repel. Thus two electrons, both carrying negative charges, repel each other. Attraction between opposites and the repulsion of likes are the forces that drive electrons through circuits.