Fundamentals on Fabrics and Garment Construction

In This Chapter

▶ Identifying common fabrics

▶ Understanding fabric characteristics like texture and weight

▶ Judging the quality of a garment by how it’s made

▶ Finding what works when mixing and matching different fabrics

Atrue fashionista can distinguish between designer clothing and knock-offs in a millisecond. The main way of doing that is by the fabric. It’s easy to imitate a style, but since one of the main costs of an item is the fabric, imitations are usually easy to spot if you know what to look for. And vice versa, if you find an affordable outfit by an unknown designer but recognize that it was made with quality fabric, then you’ve found yourself a true bargain.

In order to build your wardrobe properly, you must have a general knowledge of the fabric you’re buying. By discovering how to recognize quality materials and construction, you’ll be able to make better decisions on what to purchase. This chapter gives you the lowdown.

Fabric Basics Everyone Should Know

The garment industry uses hundreds of different fabrics in the making of clothes. About 220 different fabrics alone can be used to produce a woman’s suit, for example. Some of these are variations of a basic fabric, such as the many types of cottons, ranging from broadcloth to Pima, while others are made from various fibers and have unique characteristics, like brocade, which has raised designs on a flat surface. (See the later section “Fabrics and fabric blends” for a list with descriptions.)

How much do you really need to know about fabrics? Actually it helps to know quite a lot. Here’s why:

✓ One of the keys to dressing fashionably is having variety in your closet. If you have ten blouses that are identical in fabric, except for their color, it’s difficult to put together an outfit that stands out. But if your collection of blouses features lots of different fabrics as well as a variety of textures, weaves, and shades, you can put together outfits that are more unique.

✓ Knowing the different fabric varieties helps when you’re shopping. Asking a sales associate for a black blouse doesn’t really give her very much to go on. But if you say you want a black silk blouse, you’ve narrowed down the choices considerably. And if you say a black silk-satin blouse, you’ve done even more refining. Knowing one fabric from another can also help you as you scan your favorite store and look for that perfect outfit.

✓ The care of your clothing is dependent on what it’s made of. Most synthetic fibers, for example, are prone to heat damage, especially hot water in a washer as well as the heat of a dryer or iron.

Practical matters aside, the more you know about fabrics, the better you can become at selecting clothing of quality (which is the only type you should have in your 10 closet; refer to Chapter 2 for more on my 10 System).

Common fibers

There are five natural fibers (cotton, wool, silk, linen, and hemp) and five manmade fibers (acetate, acrylic, nylon, polyester, and rayon). These fibers are the building blocks of most of the material used in clothing. In some instances they’re used alone, but very often they’re blended together so that manufacturers can combine the look of one fabric (usually a natural one) with the durability of another (usually a synthetic).

Natural fibers

Natural fibers are just that — those that are found in nature. They come from plants or animals, as opposed to being chemically produced. The following lists a variety of natural fibers and explains how they’re used in clothing:

✓ Cotton: Cotton comes from a plant and is the most popular fabric, in part because it breathes. Among the fabrics made from cotton are flannel, muslin, oxford, poplin, seersucker, and terry cloth. Because cotton cloth wrinkles easily, manufacturers often blend it with polyester to make it wrinkle resistant; unfortunately, this pairing also makes it less breathable. However, today you can buy 100 percent cotton shirts that don’t need to be ironed but merely thrown in the dryer for a short time because permanent finishes have been added to them that reduce wrinkling. While such shirts are more costly, in the long run they can save you a bundle in cleaning costs.

✓ Wool: Wool comes from animals and is woven into a fiber that can be made into clothing. Wool retains heat and absorbs moisture without feeling wet so it’s particularly good as an outer layer. When treated, worsted wool holds a crease and is smooth and quite durable, making it popular for suits, skirts, and slacks. Among the types of fabrics made from wool are flannel, gabardine, tartan, and various tweeds.

Most wool comes from sheep, but the wool of other animals — such as alpaca, angora goat (mohair), angora rabbit, cashmere goat, vicuna (a type of llama), and camel — is also used.

✓ Silk: Silk is made from the hairs in the cocoon of the silk worm, and man has been using this wonderful fiber since 2,700 BC. Silk is one of the more elegant fabrics because the cloth produced is shiny and gives a dressier appearance. Among the fabrics made from silk are chiffon and doupioni, a knobby silk found in some men’s lightweight suits.

Keep your silk away from alcohol. If you’re going to put on perfume or hairspray, do so before you don a silk garment and allow the alcohol to evaporate.

✓ Linen: Linen is made from fibers in the stalk of the flax plant. It’s the strongest of any vegetable fabric, as much as three times stronger than cotton. Yes, linen wrinkles easily, but it’s also easily pressed. Linen is a good conductor of heat, which makes it perfect to wear in hotter temperatures.

✓ Hemp: Hemp comes from the stalk of the plant whose flowers and leaves make marijuana (but no, the stalk doesn’t contain any of the narcotics that give marijuana its punch). Like linen, it wrinkles easily. Because it’s considered a “green” fabric, hemp is growing in popularity, but it’s still illegal to grow hemp in the United States and so the fabric is usually imported from China.

Cleaning silk

Though many people think silk has to be dry cleaned, it’s a natural fiber that was used for eons before such a thing as dry cleaning existed. That means it can definitely be washed, but you have to know how:

✓ Hand-wash your silk garments. The agitation of a washing machine can damage silk

clothing.

✓ Use lukewarm water and a non-alkaline detergent and don’t leave silk garments to soak. Never expose silk to bleach or deter- gents with brightening agents. If you notice a soapy residue, add a spoonful of vinegar to the rinse water.

✓ To dry silk, lay the garment down on a towel that will absorb the moisture. Don’t dry silk in the dryer or in the sun.

Note: If a silk garment has care instructions that say, “Dry clean only,” that may mean the manufacturer hasn’t taken the precaution to preshrink the fabric and didn’t use color fast dyes — in other words corners were cut. If that’s the case, make sure you dry clean that item so that it doesn’t shrink or fade and ruin the garment.

Manmade fibers

While natural fibers require just some simple processing, manufactured fibers are a little more involved. They start as various combinations of raw ingredients that you may not associate with clothing at all, like petroleum and wood pulp. These substances are turned into fiber using techniques that have only been around for the last century or less. Manufactured fibers can have advantages over natural fibers. For example, they can be made into hollow tubes that offer loft without the weight (such as those found in winter overcoats) and microfibers that are excellent at repelling water.

✓ Acetate is made from wood pulp. It can have the look of silk, dries quickly, and drapes well. If you own clothing made from acetate, keep it away from acetate in its liquid form, such as nail polish and nail polish remover. Liquid acetate will damage the acetate fabric.

✓ Acrylic is a synthetic fiber, meaning it’s manufactured from petroleum products. It has the bulk of wool, draws moisture away from the body, and can be washed. It also dries quickly, but melts if it becomes too hot.

✓ Nylon, the first completely synthetic fiber, entered the fashion world in the form of stockings introduced in the 1940s. It’s lightweight but strong, and its fibers are smooth and dry quickly. After many washes, nylon tends to “pill”; it also melts at high temperatures.

✓ Polyester fibers are strong and wear very well. Because it doesn’t absorb water easily, it dries quickly. The downside is that polyester doesn’t breathe. Unfortunately, polyester got a bad name for itself when it was used in double-knit fabric that was popular for a while in the 1970s and then became overused. Today, polyester is often used in a blend with cotton or other fibers.

✓ Rayon is created from wood pulp, and it shares many of the qualities of cotton. It’s strong and absorbent, comes in a variety of qualities and weights, and drapes well. If rayon is washed before being made into a garment, it’s a washable fabric.

Fabrics and fabric blends

Given the relatively limited number of fibers — manmade and synthetic — that are used to make clothing, you may wonder how there can be so many fabrics. The answer has to do with how a fiber is woven, whether the fibers are blended, and what finishes are applied. This section gives you a quick rundown of a variety of fabrics and fabric blends.

A glossary of fabrics

Below is a quick look at the different fabrics and the weaves that can be constructed from them. It’s a good idea to become familiar with these fabrics

(at least on a general level) so you know what you’re looking at the next time you’re deciding between garments.

✓ Boucle: A plain or twill weave made from looped yarns that give it a textured, nubby surface.

✓ Broadcloth: A fine, tightly woven fabric, either all cotton or a blend, with a slight horizontal rib.

✓ Brocade: A decorative cloth that is characterized by raised designs. It’s usually made of silk, sometimes supplemented by actual silver or gold threads.

✓ Calico: A plain-weave cotton fabric printed with small motifs.

✓ Cashmere: A wool, woven from the fleece of the Cashmere goat, that is both very soft and exceptionally warm. Because of the difficulty of separating the fine fibers from the surrounding coarse hair, cashmere is a luxury product.

✓ Chantilly lace: Lace with a net background and floral design patterns created by embroidering with thread and ribbon.

✓ Chiffon: A lightweight, extremely sheer and airy fabric with highly twisted fibers. Often used in full pants and loose tops or dresses.

✓ Corduroy: A fabric, usually made of cotton or a cotton blend, that uses a cut-pile weave construction. The wale is the number of cords in one inch.

✓ Crepe: A fabric that has a crinkled, crimped, or grain surface and that can be made from several different materials. Crepe de chine is made of silk and comes in various widths, with 4-ply considered the most luxurious.

✓ Duck: A closely woven, plain, or ribbed cotton fabric that is very durable. It’s similar to canvas but lighter in weight.

✓ Dobby: A decorative weave that has small patterns, often geometric.

✓ Faille: A closely-knit fabric that is somewhat shiny and has flat, crosswise ribs. Faille can be made from cotton, silk, or synthetics.

✓ Gabardine: A twill weave, worsted fabric that can be made from wool, cotton, rayon, or nylon, or blended, with obvious diagonal ribs.

✓ Gingham: A fabric made from various yarns, most often in a checked pattern.

✓ Herringbone: A twill weave with a distinctive zigzag effect.

✓ Microfibers: An extremely fine synthetic fiber that can be woven into textiles with the texture and drape of natural-fiber cloth but with enhanced washability, breathability, and water repellency.

✓ Satin: A lustrous fabric most often used in evening wear.

✓ Spandex: A stretchy fabric that offers comfort, movement, and shape retention. It is also known by its brand name Lycra (created by DuPont).

✓ Taffeta: A crisp, tightly woven fabric with a fine crosswise rib that’s easily identifiable by the rustling sound that it makes. Originally all taffeta was made from silk, but today it can be made from a variety of synthetic fabrics, sometimes combined with silk.

✓ Velvet: A luxurious fabric once exclusively made from silk but that today can be composed from a number of different fabrics including cotton.

The dense loops, which may or may not be cut, give it a plush feel.

Fabric blends

Blending fibers in a fabric can help prevent wrinkling or lower the cost of a garment. Here are a few examples of blends and their advantages:

✓ Polyester and cotton: Polyester is crease resistant; cotton isn’t. A gar- ment that blends the two may not need to be ironed or will require less ironing, while retaining much of the comfort provided by cotton.

✓ Linen and silk: Linen creases easily while silk doesn’t. By adding silk to linen, a garment won’t crease as readily and will drape better.

✓ Spandex and cotton: Spandex is stretchy and durable, and cotton lets your skin breathe. The two make a perfect combination for sports clothing.

✓ Cotton, polyester, and rayon: Cotton offers breathability, polyester strength, and rayon shininess. A fabric with all three offers durability, ultra-softness, and excellent resilience so that if wrinkled, the fabric bounces back.

How fabrics are made

To get the different types of fabrics used to make clothing, the fibers have to be turned into threads or yarns and then woven or knit together. Which

fibers (or combination of fibers) are used and how they’re put together deter- mine what type of fabric is made. The higher quality fibers used, the better the quality of the fabric and (provided that the fabrics are designed and sewn together well) the better the overall quality of the final garment.

Step 1: The making of the thread

Since natural fibers are originally “manufactured” by Mother Nature, they don’t necessarily come in the appropriate format for making cloth, which is why they have to be fabricated. The natural length of a fiber, say the wool that comes off of a sheep, is called the staple. The staples are then twisted together to make the thread or cloth that’s needed for turning out actual fabric. Manmade fibers, on the other hand, come out of the manufacturing process as threads, as they are mostly chemicals spun together using various processes.

Step 2: Knitting or weaving the threads together

Fibers are manipulated in several different ways to make clothing. The first is knitting, which involves using hooks to loop the yarns together. You may be most familiar with the type of hand knitting that people do at home with a single set of needles, but knitting machines can produce much more sophisticated fabrics. Fabrics in the jersey family, for example, are knitted. Knitted fabrics have more stretch than woven fabrics.

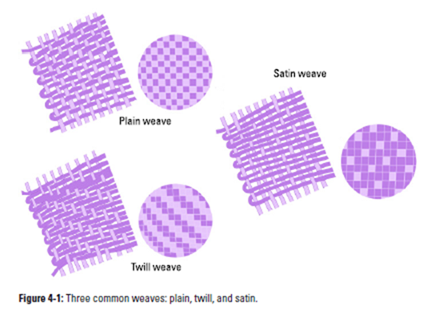

Weaving is the most common form of making fabric. A woven fabric is made by interlacing threads of one or more types of material. Originally weaving was done by hand, but then the loom was invented and simplified the pro- cess. Today, computerized looms can produce amazing designs. Following are the most common weave designs, as shown in Figure 4-1:

✓ The plain weave: Early woven patterns were plain, with one set of threads going over and under the other set. The technical term for the yarn going over is the warp yarn; the term for the yarn going under is the weft yarn. The plain weave is still used today in the making of chiffon and taffeta.

✓ The twill weave: In the twill weave, the weft yarn passes over at least two but not more than four warp yarns, moving one step to the left or right with each line. The corded effect produced in twilled fabric greatly adds to the fabric’s durability. Some examples of twill weaves include denim and gabardine.

✓ The satin weave: The satin weave is similar to the twill except the warp yarn passes over four to eight weft yarns, yielding the characteristic sheen of satin cloth.

Some other common weaves include the rib weave, which has a higher concentration of yarn going in one direction to produce broadcloth and poplin; pile weave, which forms loops used to make terrycloth; and dobby and jacquard weaves, which combine various weaves to make patterns.

Make sure you understand the difference between weaves and fibers. Many different fibers can be woven to make satin, including silk, polyester, acetate, or even a blend. So if you’re looking for a satin blouse, don’t make the mistake of thinking that all satin is the same, because while the weave is the same, the fibers that are woven together to make satin can be different.

Step 3: Finishing

The last step in making fabric is finishing. A finish can add many types of effects, changing the appearance and texture. For example, flocking, which uses adhesives to add material, produces a fuzzy texture. Other finishes add water repellency, moth resistance, flame resistance, or pilling resistance.

Finishing touches from ancient times to today

While finishing may seem like a new technique, and most of the finishes added today are quite new, the Chinese were known to flock cloth in the year 1,000 BC, though for decorative purposes only.

In recent years, a new attribute to clothing has been resistance to the damage the sun’s UV rays can have on the skin. By using a high thread count, often with some chemical finishing as well, some fabrics can offer a degree of protection against UV ray penetration. Of course, the garment can only protect the body part it’s actually covering.

Understanding how your clothing is made allows you to choose garments that are well-constructed, keep their appearance, and are easy to maintain. If you’re buying a trendy item that you don’t plan to wear for more than a season, you can use this information to your benefit as well — that is, don’t buy a trendy item in one of the more expensive fabrics because it’s a garment you don’t plan to wear for years to come. But again, if you’re purchasing a quality piece for your wardrobe, you want to make sure that you’re making an investment in a quality fabric that can stand the test of time.

From smooth to rough: Texture

Texture, the surface appearance of a fabric, is a result of the type of fibers used in the manufacturing process and the weave or knit. Texture is the one element you can both see and feel. Texture is defined by the thickness and appearance of a fabric, and words that describe texture include furry, soft, shiny, rough, smooth, and sheer.

In general, the more dressed up you’re going to be, the more likely the texture of your clothing is going to feel soft to the touch. And because most manmade fabrics can’t match Mother Nature when it comes to the combination of softness and durability (think of how strong the light threads of the silkworm are when woven together into cloth), natural fabrics are considered more luxurious than manmade fabrics.

When considering a garment, be aware of the effect the texture has on your overall look:

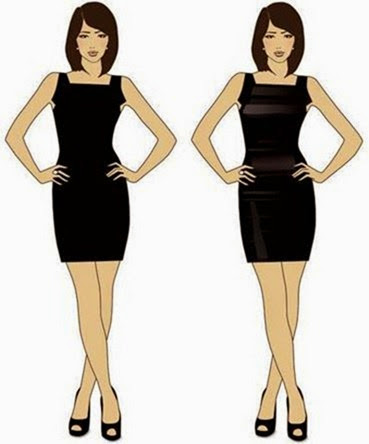

✓ Textures that make you look bigger: Some textures — shiny textures that reflect light, or thick and bulky textures, for example — make you appear bigger in a garment. Stiff fabrics do the same. In order to avoid looking bigger, try matte fabrics and smoother, less bulky materials.

Also, don’t wear fabrics that are too stiff, such as coarse tweed. Figure 4-2 shows the difference between a matte fabric and a shiny one.

If you’re petite, you may not want to buy clothing with a very coarse fabric, because while it may add to your size, the coarse look may also overwhelm your small figure.

✓ Textures that make you look thinner: Fabrics that have smooth, flat surfaces and a dull or matte surface that absorbs light can make you appear thinner. These fabrics include matte jersey and cashmere.

Soft or clingy fabrics show the shape underneath the garment, which may or may not be something you want. While they don’t increase your size as far as width or breadth, they do show every curve, so if you don’t want to draw any added attention to your hips or rear, avoid these materials, too. Opt for something with a bit more structure.

Figure 4-2: Matte (left) versus shiny (right) can alter your appearance.

Transparent versus opaque

While most of the material used to make clothes is opaque, that is, what lies underneath it cannot be seen, that’s not true of all cloth. Transparent cloth is also used in clothing. Transparent fabrics are light and flowing, and they give a very feminine look.

Unless the transparent garment is a piece of lingerie, the wearer usually has some other item of clothing underneath, like a flesh-colored bra under a sheer blouse to maintain whatever degree of modesty is desired. What you wear underneath depends on where you are as well as your level of modesty. If you’re going out on the town, you may choose to wear no more than a bra. While in the office, a camisole would be more appropriate (see Figure 4-3).

Figure 4-3: Where you’re going dictates how much layering you do.

Key Features of a Garment

Knowing about fibers, fabrics, and weights is only part of the information you need to be a savvy shopper. You also need to know about garment construction. Even if you never buy a hand-sewn designer gown for thousands of dollars, you still need to know what to look for when buying a piece that fits your budget.

Stitching

Most stitching is utilitarian and not something you need to concern your- self with — except when it’s not done well and the garment falls apart while you’re wearing it (at which point you’ll have learned the hard way to appreciate good stitching).

The basic stitch is called the straight stitch. Other types of stitching include

✓ Zigzag: A stitch used for garments that require some stretch. One stitch goes left and the next right.

✓ Baste: A simple stitch used to just hold pieces of cloth together before final sewing.

✓ Buttonhole: A stitch used to make buttonholes.

✓ Back: A stitch in which the thread is sewn backward as compared to other threads to outline decoration.

In general, stitching (unless it’s decorative) isn’t supposed to be noticeable because its function is merely to hold the garment together. While stitching often does not add to a garment’s appearance, you can often figure out a garment’s overall quality — and know whether you’re paying a good price for it — by checking the stitching. Some things to look for are

✓ How many stitches there are per inch: The more stitching per inch, the stronger the garment. Sixteen to 20 stitches per inch defines the high- end. Of course, some stitching is merely decorative, such as the type you may see made into a pattern on the back pocket of a pair of jeans.

✓ Whether it’s machine sewn or hand sewn: While machine stitching is usually acceptable, in some cases, where attention to detail is demanded, hand sewing is superior. If a garment’s label indicates that some hand sewing took place in its creation, you can be sure that it’s a quality item, since hand sewing takes a lot more effort and costs more to produce. At the other end of the spectrum, instead of stitching the pieces of fabric together, the pieces may be fused together, a less expensive method of production and one not guaranteed to last very long.

✓ The type of thread used. The threads used can be made from various materials. Silk threads are strong yet thin, providing the very best stitching. Cotton threads are next in line, and synthetic threads can per- form their job well even though they’re not quite as good quality as cotton.

Another way to spot a piece that may not be well-constructed is to look on the inside for seams where the stitching is most apparent. Check to see whether the stitching looks neat and the ends are tied off. If you see a lot of loose threads, then you know this garment is not of the highest quality.

Seams

The seam is where two pieces of a garment are stitched together. Major seams are hidden away inside the garment (as opposed to hems, which are seams at the base of edges, such as at the bottom of a skirt, and can’t be hidden completely). Note that this isn’t true in some articles of clothing, like jeans, where the seams are part of the overall look.

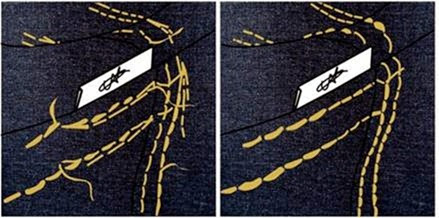

Because most seams are hidden, they’re not usually made to look pretty. French seams are an exception (see Figure 4-4). These seams are doubled over so that, if visible, they appear a lot neater. (French seams won’t work where the material is too bulky, however, because the folded over material makes too much of a bump.)

Figure 4-4: A French seam.

To learn more about the quality of a piece of clothing, do the following when you’re looking at seams:

✓ Check how tightly knit and strong the thread is. If the seam appears to be tightly knit together with strong thread, that’s the sign of a better quality garment. But if the spacing between the threads is wide and the thread looks weak, you can be sure the manufacturer was cutting corners, and the seam is probably not the only place.

✓ Give the seam a good tug. This gives you some solid evidence of the care that went into its construction.

✓ If there’s a lose thread, pull on it. It may just be some extra material, and nothing will happen except that it will pull away. But if the seam starts to unravel when you pull on the thread, put that garment back and start looking for another one.

✓ Pay particular attention to curved seams. Curved seams are used when two curved pieces of cloth must come together, such as when attaching sleeves to the body of a shirt or jacket. While many people learn to sew a simple plain seam in order to make hems, mastering the curved seam is more difficult and a poorly made jacket may not have the proper curved seams where they’re required. Figure 4-5 shows a well-sewn curved seam compared to a poorly sewn one.

✓ See how much extra material is at the seam. On a regular pair of pants, you’ll notice that there’s extra material at the waist seam. This extra material is there so that the seam can be let out. Better quality clothing usually has more material to allow for such alterations. (Note: The seams on jeans, called flat felled seams, don’t provide this extra material. This type of seam was originally used because jeans were considered work pants and the flat felled seam is very strong. The disadvantage is that there is no extra material.)

Figure 4-5: Poorly sewn curved seam (left) and a well-sewn curved seam (right).

Making the cut

One of the most important elements in making clothes is the cut — how the finished product is put together. The cut not only affects the garment’s appearance but also its comfort. In an expensive jacket, for example, the

design calls for a curve where the arms get attached to the body of the jacket to accommodate the way your arm moves; you’ll notice the difference both in the jacket’s appearance and how it feels. In a less expensive jacket, the cut is straight up and down. Not only does it not look as good as the more expensive jacket, but it feels even worse as material hits under your arm instead of flowing around it.

You find such differences in almost every type of garment, from expensive designer gowns to blue jeans. In better quality jeans, for example, the two legs are separate units and the last seam is around the crotch. In less expensive jeans, the legs are part of the front and back and the last seam is up and down the inside of the leg. The first method gives you a much better and more comfortable fit. Figure 4-6 compares a well cut jean with a poorly cut jean.

Figure 4-6: The proper cut (right) makes all the difference in the appearance of a garment.

If you’ve always wondered how a particular item of clothing can cost so much, it’s worth going to a high-end store and trying on some designer pieces (even if you never plan on buying anything). Often, you’ll see how different the fit and feel actually are.

Mixing and Matching Fabrics

Here’s the thing about mixing and matching fabrics: You can as long as it looks right. The following sections have the details.

Fashion rules aren’t just arbitrary edicts sent down from above. Instead, they’re based on a common denominator: what looks right and what doesn’t. While not everybody agrees on these rules, the vast majority of people do find certain looks pleasing and others unpleasant. Using this as a guide certainly makes it easier for you to choose your outfit each day.

A word about weight

In the fashion world, weight refers to the thickness of the thread. The thicker the thread used, the heavier the cloth that is woven from it. In most cases, especially when comparing very similar fabrics, the heavier a fabric is, the more material it contains, the higher the quality, and the more it costs. The difference in weight is sometimes more apparent in the simplest of garments. If you have a choice between two cotton T-shirts and you’re wondering why one is a lot more expensive than the other, pick each one up and compare their weights. Odds are that the heavier one, which has more cotton threads per square inch, is the more expensive one.

Three standards for measuring weight are ounces per linear yard, ounces per square yard, and grams per square meter. It’s important to know which unit is being used when being given the weight of a cloth because something that would be lightweight in one would be heavyweight in another. In the United States and Asia, fabric weight is more likely to be given in ounces, while in Europe it’s grams.

In addition to using weight as an indication of quality, there are also practical aspects to choosing the weight of a garment. While you may want a suit with extra weight in winter to keep you warm, in summer you’ll choose lighter weight material.

You can certainly combine weights of clothing, but you don’t want the contrast to be too great. For example, you wouldn’t wear summer weight linen pants with a thick wool sweater. Basically, you want to make sure the two fabrics are meant for the same season. So while you wouldn’t pair heavy wool with linen, you can pair heavy wool with corduroy (see Figure 4-7). Use your common sense. The reason you wear these fabrics when you do is generally to keep warm in winter or cool in the summer.

Figure 4-7: A bad pairing (left) and a good pairing (right).

Pairing patterns

Don’t be afraid to pair patterns. You can find many ways to make this work. The biggest key is to keep everything in the same color family. If you’re going to wear two different patterns, the colors have to match (see Chapter 5 for more on color). The other thing to remember when pairing different pat- terns is balance. If one print or pattern is big and bold, make sure the other one is small. If you’re just starting out, and not sure exactly how this works, start with something small: Pair a patterned blouse with a printed scarf and a solid pant or skirt. Just make sure all the colors in the blouse and scarf work together and that the pattern on one of the pieces is small, if the other is large.

It’s a bit easier to see what to avoid when you examine extremes. Wearing two bold patterns, say polka dots with stripes, certainly risks causing a visual clash. But what about two stripes? It depends on the stripes. Do the colors compliment each other? Are the stripes the same size or is one set wider than the other? Do they go in the same direction? Obviously the combinations are

endless, and I can’t possibly go over all of them, so to some extent you have to develop your own eye and learn to trust it. But here are some rules that you can use to help you combine stripes:

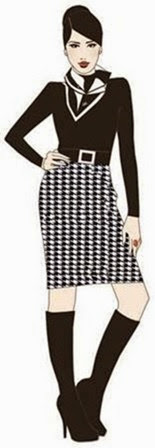

✓ Make sure they’re not the same size, which creates too much tension. If one stripe is a lot broader than the other, then they can work together, assuming the color combinations also work. If your patterns don’t match, better to pair with a solid, as Figure 4-8 shows.

✓ Keep everything else in your outfit simple. If you’re going to combine two stripes, anything else has to be simple and in neutral tones so as not to make the whole effect far too busy.

The same concept holds true for checks, with one caveat: Because checks are more intense, you have to be even more careful when wearing two differ- ent checks. Wearing two different checks of similar size is disorienting to the viewer’s eye. But if you have one small check, like a houndstooth pattern, a larger check can work, though their colors would have to complement each other.

Figure 4-8: A mismatched outfit (left); a better alternative (right).

When it comes to combining patterns, like stripes and checks, it’s best if one of the two is on an accessory item (see Figure 4-9). You can pair a jacket with checks, for example, with a striped scarf, as long as the colors complement each other. But you wouldn’t want to wear a striped skirt with a checked blouse. Yikes! You also need to consider the scale of each pattern. Again, you don’t want the scale and colors to match too closely because then the look is discordant. Instead, choose scales that contrast one another: If one pattern is small, like narrow stripes set far apart, then the checks can be more dense and larger.

If you’re thinking of combining three patterns, don’t. Unless you really know what you’re doing, three different patterns can easily come off looking way too busy. For the most part, picking one pattern or item to accentuate is the way to go.

Figure 4-9: Two patterns working together well.