Splitting Hairs: Growth, Loss, and Change over Time

In This Chapter

-

Looking inside a hair follicle

-

Feeling the difference: Comparing hair types

-

Seeing how hair changes as you age

Not all hair is the same. Some people have thick, some thin; some is beautifully blonde, some is a glossy black; some is shiny, some is dull. Depending upon where hair is on your body, some grows long and some short, some is straight and some curly. Knowing more about the characteristics of hair and what type of hair you have is particularly important when your hair thins and falls out because coverage and the appearance of fullness in a balding person critically depends upon the characteristics of the hair and skin color.

Although understanding some of the factors that contribute to hair loss can’t necessarily help prevent the loss, understanding the fundamental relationships between hair and skin color, hair density, bulk, and other characteristics can help you maximize the fullness you can achieve as well as guide you in your replacement options.

In this chapter, we explain the parts of a single follicle and hair shaft, how hair grows, the different hair types, what causes those differences, and some factors that can slow its growth, including age and ethnicity. We share all this with you to arm you with the knowledge you need to assess your own hair situation and investigate the options available to you to deal with it — whether you’re thinking about replacement or transplantation or just creative hairstyling.

Under the Microscope: Hair and Scalp Anatomy

Hair is much more complex than it looks. In this section, we describe how hair follicles grow and alter with time and other factors. Understanding how hair follicles function (and what makes them stop functioning) can help you maintain them, thereby slowing the hair loss process.

Going beneath the skin

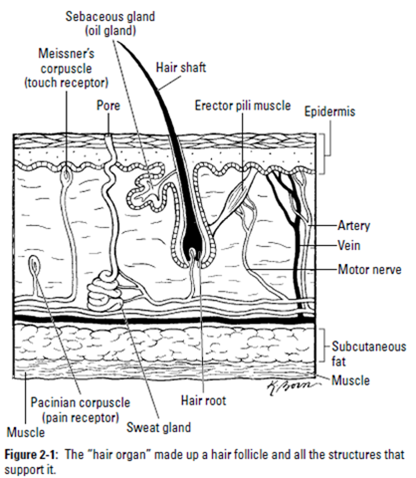

Most people think of hair only in terms of what they see above the scalp, but hair is actually a rather complex organ that goes beneath the surface. Anatomically speaking, hair is part of your skin. But because hair is physically distinct from skin, it’s referred to as a skin appendage. (Other skin appendages include sweat glands, fingernails, and toenails.) See Figure 2-1.

Skin is composed of three main layers:

-

The epidermis: This outer layer of the skin is less than 1 millimeter thick. It’s composed of dead cells that are in a constant state of sloughing and replacement. As dead cells are lost, new ones from the growing layer below replace them.

-

The dermis: This tough layer of connective tissue is about 2 to 3 millimeters thick on the scalp. This layer gives the skin its strength and contains both sebaceous (oil) glands and sweat glands.

Sebaceous glands produce an oily substance, which creates a plug of wax (sebum) to cover the opening to the growing hair follicle. As the hair grows upward from the skin surface, some of the waxy substance is taken up by the hair shaft as a lubri- cant, giving the hair a waxy sheen.

Sweat glands help control body temperature, particularly when it’s hot. These glands produce a watery, salty sweat; as the sweat evaporates, body heat is lost.

-

Subcutaneous fat and connective tissue: This layer contains the larger sensory nerve branches and the blood vessels that nourish the skin. In the scalp, the lower portions of the hair follicles (called the bulbs) are found in the upper part of this fatty layer.

Dissecting a hair follicle

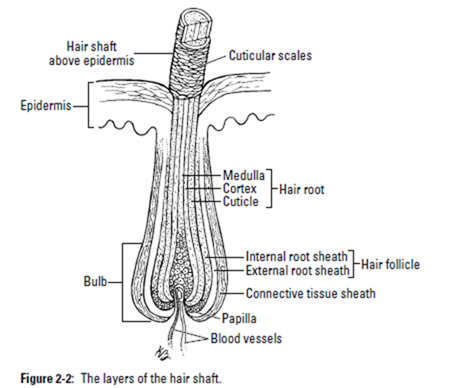

The hair follicle must function properly in order to maintain a healthy head of hair. A hair follicle is a complex structure that measures about 4 to 6 millimeters in length. Each follicle produces one to four hair shafts, each about 0.1 millimeters in width (in other words, these are really, really tiny structures).

The layers of a hair follicle

Hair follicles have three layers surrounding the strand of hair, which you can see in Figure 2-2:

-

The outer root sheath, or trichelemma: This is the outer layer, which surrounds the follicle in the dermis and then blends into the epidermis on the surface of the skin, forming the pore from which the hair grows.

-

The inner root sheath: This middle layer is composed of three parts, with the cuticle being the innermost portion that touches the strand of hair. The cuticle of the inner root sheath interlocks with the hair cuticle (described in “the layers of the hair shaft” section) to give it rigidity.

-

The bulb: This is the lower portion of each hair follicle. It contains the inner matrix cells, which produce bundles (also called spindles) of hair cells that look like fine wires in an electric cord. These bundles are actually made up of even smaller bundles, which literally twist as they’re made. The size of the bulb and the number of matrix cells determine the width of the fully grown hair.

The layers of the hair shaft

The hair shaft is composed of three layers.

-

The cuticle: This layer forms the surface of the hair and is what you see as the hair shaft emerges from the follicle.

-

The cortex: This middle layer comprises the bulk of the hair shaft and is what gives hair its strength. It’s composed of an organic protein called keratin, the same material that comprises rhinoceros horns and deer antlers.

-

The medullas: This is the center, or core, of the hair shaft, and it’s only present in terminal hair follicles (a fully grown hair).

The dermal papillae

At the bottom of the hair follicle, there is a bulbous (bulb) portion which contains a small collection of specialized cells called the dermal papillae. Scientists believe these cells are at least partially responsible for determining. how long the hair will eventually grow, how thick it will be, and the character of the hair will be.

For many years, scientists thought that hair actually grew from the dermal papillae. Recent evidence shows that the growth center is not totally controlled from the dermal papillae. Elements that control hair growth can be found all the way up to the region of the follicle where the sebaceous glands are attached.

If the dermal papillae is removed (which sometimes happens during a hair transplant (see Chapter 13), the hair follicle may still be able to regenerate new hair, although the new hair may not be a characteristically healthy looking terminal hair. It may be shorter, thinner, and more kinky or wavy.

How hair grows

Hair doesn’t grow in individual strands but rather emerges from the scalp in groups of one to four (and sometimes even five or six) strands. Hair follicles are arranged in the skin in naturally occur- ring groups called follicular units.

At any given time, about 90 percent of a person’s terminal hairs are actively growing. This growth phase, called anagen, can last for two to seven years, though the average is about three. Scalp hair grows at an average rate of about 0.44 millimeters a day, or about 1⁄2 inch per month.

The 10 percent of scalp hairs not actively growing are in a resting state called telogen that, in a healthy scalp, lasts about three to five months. When a hair enters its resting phase, growth stops, the bulb detaches from the papilla, and the shaft is either pulled out (as when combing one’s hair) or pushed out when the new shaft starts to grow.

Hairs grow in naturally growing groups of one to four hairs each. These are called follicular units. The follicular unit has two types of hair. The terminal hair and a vellus hair or two. These vellus hairs are smaller, shorter, and finer than the terminal hairs found in the follicular unit.

When a hair falls out on its own, a small black bulb can often be seen at the end of the hair. If it’s pulled out while it is in its growth (anagen) phase, it will produce pain when it is pulled out and a white, sticky mucus swelling will often be seen at the bottom of the hair shaft. Most people assume that this is the growth center of the hair and that pulling it out means the hair won’t grow again.

But cells of the dermal papillae and the growth centers found along the side of the hair shaft near the sebaceous gland will remain in the place after the hair is pulled out. These cells will multiply and cause a new hair to grow at the same location in a month or so. So pulling out a single hair should not kill that hair.

Humans lose about 100 hairs per day. The presence of a much larger number of hairs on your comb, in the sink, or in the tub can be the first sign of excessive hair loss. We become sensitized by balding in our family history and a thinning appearance on the scalp. Although we may see hair in the drain often, if we are not balding or thinning we might think nothing of it.

Letting down your hair

You’re probably familiar with the Grimm’s fairy tale about Rapunzel, a young maid who was put into a high tower when she was a girl. One day, a prince heard her crying and was smitten by her beauty and her long blonde braided hair. When he couldn’t find a door into the tower to rescue her, he asked that she let down her golden hair so he could climb up and rescue her. The beautiful Rapunzel let her hair hang over the edge of the tower, and the prince scurried up to her rescue. After some harrowing events, they lived happily ever after.

It’s a good story but, notwithstanding freakish exceptions (the current world record hair length is more than 18 feet), clearly the Brothers Grimm weren’t well-versed in the biology of normal hair growth. They couldn’t have known that the longest growth phase of hair is growth was six or seven years, making Rapunzel’s hair a maximum of about 1 meter in length (that’s six or seven years at 1⁄2 inch per month). Certainly, Rapunzel could have jumped from a height of 1 meter, but if she had, the Brothers Grimm wouldn’t have had much of a story for the millions of children who wanted to believe in the magic of the prince who rescues the fair maid. Ignorance is bliss!

Linking Ethnicity with Hair Type and Loss

People aren’t all created equally — with respect to hair. Ethnicity and race affect your hair type and density, as we explain for the three ethnic groups in the following list. Keep in mind that although certain ethnicities are more likely to have a certain type and density of hair, variations do exist. There simply isn’t enough space in this book for us to go into that much detail.

Why should you know about the connection between your ethnic- ity and the type of hair on your head? Hair is a specialized organ system probably related, in some cases, to the climates we’re born into. For example, the African’s dark skin protects against strong sunlight and sun burns, and his kinky hair becomes an efficient heat exchanger to keep the body cool while providing some shade from the hot sun.

There are, however, no explanations for the typically straight, lower density hair of Asians when compared to Caucasians, or the high density hair counts of many Northern Europeans.

-

Caucasian hair: Generally, Caucasians have the highest number of hairs on their scalp. The density of hair on a typical Caucasian averages 200 hairs per one square centimeter. A healthy Caucasian human scalp contains about 100,000 follicles that produce thicker terminal hairs. (In comparison, the human body has approximately five million non-scalp follicles that produce the fine, vellus hair scattered around the body.) Caucasian hair generally appears thick because it’s more difficult to see through to the scalp than on Asians and Africans.

-

Asian hair: Asians have fewer scalp hairs than Caucasians, with about 140 to 160 hairs per square centimeter on the average. A healthy Asian human scalp contains about 80,000 follicles. sian hair tends to be straight and with a low density. Visually, it doesn’t cover the head as well as the curly or wavy hair of Caucasians. But some Asians have the coarsest and thickest hairs, which can offset their lower hair density.

Visually, straight Asian hair just doesn’t cover well, and with their lower densities, the problem of see through hair is compounded.

-

African/African American hair: Of the three groups we outline here, African Americans have the lowest density of hair,

ranging from 120 to 140 hairs per square centimeter. A healthy African or African American human scalp contains about 60,000 follicles.

Some Africans and African Americans actually have fine hairs, and some is kinkier than others. Because African hair often sticks together, it may appear that there’s more hair despite the low hair densities that are characteristic of all Africans and African Americans. Africans generally have a dark skin which obscures the lower densities because of the low con- trast between hair and skin color.

Aging Hair: How It Changes with Time

Like the rest of you, your hair is impacted by age, sometimes for the better, and other times, for the worse. There’s nothing you can do to stop time from marching on in your hair cells, but knowing what changes to expect can help you plan for ways to compensate for them through the use of hair growth stimulating medications, by styling changes.

Knowing what’s normal and what’s not as you age may also help you recognize early genetic hair loss and plan to treat it early, as medications and transplantation work best when you still have enough hair to work with.

Change of texture

Whether a baby’s hair sticks up all over or forms only a few wispy curls, all baby hair is baby fine. But hair changes during childhood. It remains soft but becomes bulkier. Through the teenage years and into early adulthood, hair takes on an adult texture, becoming coarser as a rule.

Hair counts are thought to be maintained well into the senior years, at least for half of the human population. The other half experiences hair loss prior to reaching their 50s.

The weight of each individual hair shaft is genetically imprinted in your genes, as is the number of hairs you’re born with. It’s not unusual for an adult to start off with a medium-coarse hair shaft, only to find that as he or she ages, the hair becomes finer as the thickness of the hair shaft changes in adulthood.

This change is slow and, provided that the number of hairs on the head doesn’t drop off precipitously, the change usually isn’t alarming.

Of those men who have a full head of hair into their 60s, nearly half will experience a substantial reduction in the thickness of each individual hair shaft.

One in three women will also experience an overall pattern of thinning hair in menopause, due to an increased sensitivity to the male hormone testosterone.

Loss of hair

The presence of baldness genes and the hormone DHT (see Chapter 4 for more on DHT and its role in hair loss) alone aren’t enough to cause baldness. Even after a person has reached maturity, susceptible hair follicles must continually be exposed to the hormone over a period of time for hair loss to occur. The age at which these effects finally manifest themselves varies from one individual to another and is related to a person’s genetic composition and to the levels of testosterone in the bloodstream.

Although balding can start in men in their teens, it’s unusual to see it much before the age of 17, when there appears to be a genetic switch that starts the process. For example, a 15 year old may have a full head of hair until, all of a sudden, he passes an age in the later teens (usually between 17 and 19) and a genetic switch is flipped on and he starts losing his hair.

Hair loss doesn’t occur all at once, nor does it occur in a steady, straight-line progression. People losing their hair experience alternating periods of slow and rapid hair loss and even note periods of stability. Many of the factors that cause the rate of loss to speed up or slow down are unknown, but it’s proven that with age, a person’s total hair volume decreases.

Even if there’s no predisposition to genetic balding, some hairs randomly begin to shrink in width and not grow as long as a person ages. As a result, each group of hairs contains both full terminal hairs and thinner hairs (similar to the finer hairs that grow on the rest of the body), making the scalp look less full.

Eventually, some of the thinner hairs are lost, and the actual number of follicular units may be reduced (for an explanation of follicular units, refer to the earlier section, “How hair grows”). In about one third of adults, even the hair around the back and side of the head (the fringe area) gradually thins over time.

Fortunately, in most people, the fringe areas of hair retain enough permanent hair to make hair transplantation possible — even for a patient well into his 70s or 80s! In a small number of men, however, the process of hair aging may start in the 20s or 30s, resulting in a uniformly falling hair count. When this happens, transplantation is more difficult because there’s not enough donor hair left to cover balding areas.

Hair through thick and thin

Some heads of hair appear thicker than others. The thickness of the hair shaft is a factor in how full hair appears: A coarse, thicker hair shaft has more bulk than a finer hair shaft. The texture is also very important.

In Caucasians, heavy, coarse hair isn’t a common trait, but if you have it, your hair appears very, very thick. People with fine, thin hair often have a “see-through” look, particularly in bright light, even if they’re not balding; a natural higher density may offset this look to some degree.

A good way to tell whether hair shafts have lost bulk between childhood and adulthood is to think back to your childhood memories. We always ask patients the following question: “When you were about 10 years old, do you remember members of your family rubbing your hair for good luck?” With the 10 year old with coarse hair, every aunt and uncle coming for a visit would rub his hair for good luck, commenting on his healthy head of hair. People who don’t recall this generally didn’t have coarse hair.

So when we see a man with see-through hair but normal hair densities, this question can illuminate the changes in hair bulk as aging occurs.

We’ve seen fair-skinned individuals color their hair to a lighter color so that the contrast between their hair and skin color is minimized, making their hair look distinctly fuller. When hair and skin have similar colors (such as blonde hair on white skin), the cover- age appears fuller than if there’s a high contrast in the colors (such as black hair against white skin).

In a hair transplant, this contrast may dictate the surgical techniques employed by the surgeon and the amount of hair that needs to be moved in order to obtain a fuller look.