5.1 The Navier-Stokes Equations

The differential continuity equation derived in Sec. 5.2 contains the three velocity components as the dependent variables for an incompressible flow. If there is a flow of interest in which the velocity field and pressure field are not known, such as the flow around a turbine blade or over a weir, the differential momentum equation

provides three additional equations since it is a vector equation containing three component equations. The four unknowns are then u, v, w, and p when using a rectangular coordinate system. The four equations provide us with the necessary equations and initial and boundary conditions allow a tractable problem. The problems of the turbine blade and the weir are quite difficult to solve and their solutions will not be attempted in this book. Our focus will be solving problems with simple geometries.

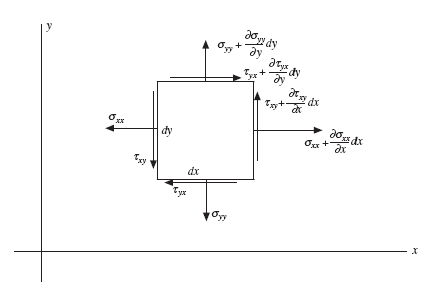

Now we will derive the differential momentum equation, a rather challenging task. First, stresses exist on the faces of an infinitesimal, rectangular fluid element, as shown in Fig. 5.2 for the xy-plane. Similar stress components act in the z-direction. The normal stresses are designated with s and the shear stresses with t. There are nine stress components: σ ![]() and τ zy . If moments are taken about the x-axis, the y-axis, and the z-axis, respectively, they would show that

and τ zy . If moments are taken about the x-axis, the y-axis, and the z-axis, respectively, they would show that

![]() So, there are six stress components that must be related to the pressure and velocity components. Such relationships are called constitutive equations; they are equations that are not derived but are found using observations in the laboratory.

So, there are six stress components that must be related to the pressure and velocity components. Such relationships are called constitutive equations; they are equations that are not derived but are found using observations in the laboratory.

Figure 5.2 Rectangular stress components on a fluid element.

Figure 5.2 Rectangular stress components on a fluid element.

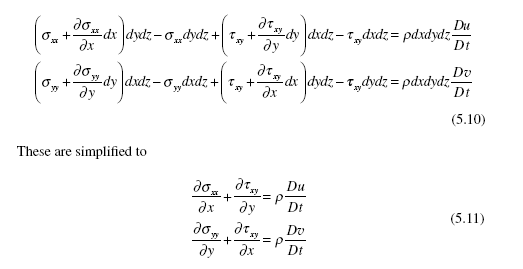

Next, apply Newton’s second law to the element of Fig. 5.2, assuming no shear stresses act in the z-direction (we’ll simply add those in later) and that gravity acts in the z-direction only:

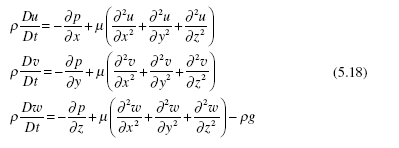

If the z-direction components are included, the differential equations become

If the z-direction components are included, the differential equations become

assuming the gravity term ρgdxdydz acts in the negative z-direction.

assuming the gravity term ρgdxdydz acts in the negative z-direction.

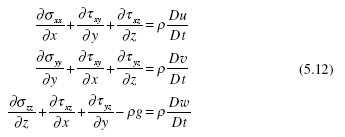

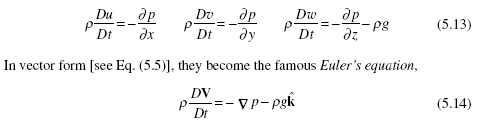

In many flows, the viscous effects that lead to the shear stresses can be neglected and

the normal stresses are the negative of the pressure. For such inviscid flows, Eq. (5.12) takes the form

which is applicable to inviscid flows. For a constant-density, steady flow, Eq. (5.14) can be integrated along a streamline to provide Bernoulli’s equation [Eq. (3.27)].

which is applicable to inviscid flows. For a constant-density, steady flow, Eq. (5.14) can be integrated along a streamline to provide Bernoulli’s equation [Eq. (3.27)].

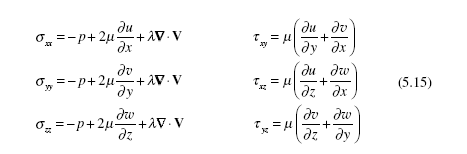

If viscosity significantly effects the flow, Eq. (5.12) must be used. Constitutive equations3 relate the stresses to the velocity and pressure fields. For a Newtonian4, isotropic5 fluid, they have been observed to be

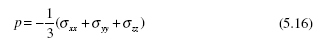

For most gases, Stokes hypothesis can be used: λ = −2μ /3. If the above normal stresses are added, there results

For most gases, Stokes hypothesis can be used: λ = −2μ /3. If the above normal stresses are added, there results

showing that the pressure is the negative average of the three normal stresses in most gases, including air, and in all liquids in which ∇ ⋅ V = 0.

showing that the pressure is the negative average of the three normal stresses in most gases, including air, and in all liquids in which ∇ ⋅ V = 0.

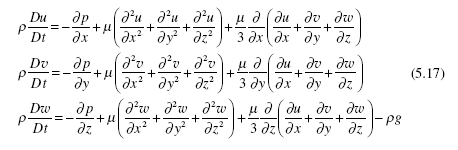

If Eq. (5.15) is substituted into Eq. (5.12) using λ = −2μ /3, there results

where gravity acts in the negative z-direction and a homogeneous fluid6 has been assumed so that, e.g., ∂ μ /∂ x = 0.

where gravity acts in the negative z-direction and a homogeneous fluid6 has been assumed so that, e.g., ∂ μ /∂ x = 0.

Finally, if an incompressible flow is assumed so that Æ ⋅V = 0 , the Navier-Stokes equations result:

where the z-direction is vertical. If we introduce the scalar operator called the Laplacian, defined by

and review the steps leading from Eq. (5.13) to Eq. (5.14), the Navier-Stokes equa- tions can be written in vector form as

and review the steps leading from Eq. (5.13) to Eq. (5.14), the Navier-Stokes equa- tions can be written in vector form as

![]() The Navier-Stokes equations expressed in cylindrical and spherical coordinates are presented in Table 5.1.

The Navier-Stokes equations expressed in cylindrical and spherical coordinates are presented in Table 5.1.

The three scalar Navier-Stokes equations and the continuity equation constitute the four equations that can be used to find the four variables u, v, w, and p provided there are appropriate initial and boundary conditions. The equations are nonlinear due to the acceleration terms, such as u∂u/∂x on the left-hand side; consequently, the solution to these equation may not be unique. For example, the flow between two rotating cylinders can be solved using the Navier-Stokes equations to be a relatively simple flow with circular streamlines; it could also be a flow with streamlines that are like a spring wound around the cylinders as a torus; and, there are even

more complex flows that are also solutions to the Navier-Stokes equations, all satisfying the identical boundary conditions.

The Navier-Stokes equations can be solved with relative ease for some simple geometries. But, the equations cannot be solved for a turbulent flow even for the simplest of examples; a turbulent flow is highly unsteady and three-dimensional and thus requires that the three velocity components be specified at all points in a region of

interest at some initial time, say t = 0. Such information would be nearly impossible

to obtain, even for the simplest geometry. Consequently, the solutions of turbulent flows are left to the experimentalist and are not attempted by solving the equations.

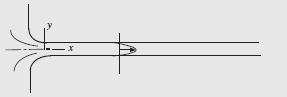

EXAMPLE 5.2

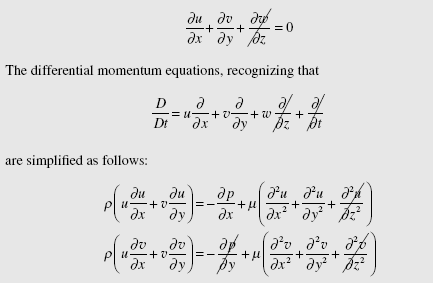

Water flows from a reservoir in between two closely aligned parallel plates, as shown. Write the simplified equations needed to find the steady-state velocity and pressure distributions between the two plates. Neglect any z-variation of the distributions and any gravity effects. Do not neglect v(x, y).

Solution

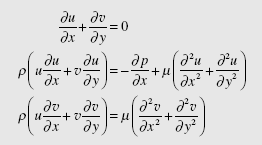

The continuity equation is simplified, for the incompressible water flow, to

neglecting pressure variation in the y-direction since the plates are assumed to be a relatively small distance apart. So, the three equations that contain the three variables u, v, and p are

To find a solution to these equations for the three variables, it would be necessary to use the no-slip conditions on the two plates and assumed boundary conditions at the entrance, which would include u(0, y) and v(0, y). Even for this rather simple geometry, the solution to this entrance-flow problem appears, and is, quite difficult. A numerical solution could be attempted.

EXAMPLE 5.3

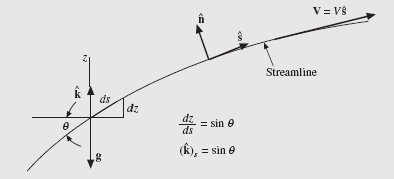

Integrate Euler’s equation [Eq. (5.14)] along a streamline as shown for a steady, constant-density flow and show that Bernoulli’s equation (3.25) results.

First, sketch a general streamline and show the selected coordinates normal to and along the streamline so that the velocity vector can be written as V sˆ, as we did in Fig. 3.10. First, express DV/dt in these coordinates:

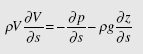

where ∂sˆ /∂s is nonzero since sˆ can change direction from point to point on the streamline; it is a vector quantity in the nˆ direction. Applying Euler’s equation along a streamline (in the s-direction) allows us to write

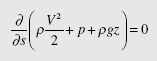

where we write (kˆ )s = ∂ z /∂s. Partial derivatives are necessary because quantities can vary in the normal direction. The above equation is then written as

provided the density r is constant. This means that along a streamline,

This is Bernoulli’s equation; it requires the same conditions as it did when it was derived in Chap. 3.

5.2 The Differential Energy Equation

Most problems in an introductory fluid mechanics course involve isothermal fluid flows in which temperature gradients do not exist. So, the differential energy equation is not of interest. The study of flows in which there are temperature gradients is included in a course on heat transfer. For completeness, the differential energy equation is presented here without derivation. In general, it is

where K is the thermal conductivity. For an incompressible ideal gas flow it becomes

For a liquid flow it takes the form

where a is the thermal diffusivity defined by α = K /ρ cp.

Quiz No. 1

1. The x-component of the velocity in a certain plane flow depends only on y by the relationship u(y) = Ay. Determine the y-component v(x, y) of the velocity if v(x, 0) = 0.

(A) 0

(B) Ax

(C) Ay

(D) Axy

2. If u = Const in a plane flow, what can be said about v(x, y)?

(A) 0

(B) f (x)

(C) f (y)

(D) f (x, y)

3. If, in a plane flow, the two velocity components are given by u(x, y) = 8(x2 + y2 ) and v(x, y) = 8xy. What is Dr/Dt at (1, 2) m if at that point r = 2 kg/m3?

(A) −24 kg/m3/s

(B) −32 kg/m3/s

(C) −48 kg/m3/s

(D) −64 kg/m3/s

2x

4. If u(x, y) = ![]() in a plane incompressible flow, what is v(x, y) if

in a plane incompressible flow, what is v(x, y) if ![]()

(A) 2y/(x2 + y2 )

(B) −2x /(x2 + y2 )

(C) −2y/(x2 + y2 )

(D) 2x /(x2 + y2 )

5. The velocity component vq = −(25 + 1/r2 )cosq in a plane incompressible flow. Find vr (r, θ) if vr (r, 0) = 0.

(A) 25(1 − 1/r 2 )sinθ

(B) (25 − 1/r 2 )sinθ

(C) −25(1 − 1/r 2 )sinθ

(D) −(25 − 1/r 2 )sinθ

6. Simplify the appropriate Navier-Stokes equation for the flow between parallel plates assuming u = u(y) and gravity in the z-direction. The streamlines are assumed to be parallel to the plates so that v = w = 0.

(A) ∂ p/∂ x = μ ∂ 2u/∂ y2

(B) ∂ p/∂ y = μ ∂ 2u/∂ x2

(C) ∂ p/∂ y = μ ∂ 2u/∂ y2

(D) ∂ p/∂ x = μ ∂ 2u/∂ x2

Quiz No. 2

1. A compressible flow of a gas occurs in a pipeline. Assume uniform flow with the x-direction along the pipe axis and state the simplified continuity equation.

2. Calculate the density gradient in Example 5.1 if (a) a forward difference was used, and (b) if a backward difference was used.

3. The x-component of the velocity vector is measured at three locations 8 mm apart on the centerline of a symmetrical contraction. At points A, B, and C the measurements produce 8.2, 9.4, and 11.1 m/s, respectively. Estimate the y-component of the velocity 2 mm above point B in this steady, plane, incompressible flow.

4. A plane incompressible flow empties radially (no q component) into a small circular drain. How must the radial component of velocity vary with radius as demanded by continuity?

5. The velocity component vq = −25(1 + 1/r )sin q + 50/r in a plane incompressible flow. Find vr (r, q ) if vr (r, 90°) = 0.

Simplify the Navier-Stokes equation for flow in a pipe assuming vz = vz (r) and gravity in the z-direction. The streamlines are assumed to be parallel to the pipe wall so that vθ = vr = 0.