The Second Law of Thermodynamics

Water flows down a hill, heat flows from a hot body to a cold one, rubber bands unwind, fluid flows from a high-pressure region to a low-pressure region, and we all get old! Our experiences in life suggest that processes have a definite direction. The first law of thermodynamics relates the several variables involved in a physical process, but does not give any information as to the direction of the process. It is the second law of thermo- dynamics that helps us establish the direction of a particular process.

Consider, for example, the work done by a falling weight as it turns a paddle wheel thereby increasing the internal energy of air contained in a fixed volume. It would not be a violation of the first law if we postulated that an internal energy decrease of the air can turn the paddle and raise the weight. This, however, would be a violation of the second law and would thus be impossible.

In the first part of this chapter, we will state the second law as it applies to a cycle. It will then be applied to a process and finally a control volume; we will treat the second law in the same way we treated the first law.

5.1 Heat Engines, Heat Pumps, and Refrigerators

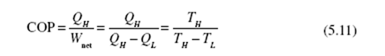

We refer to a device operating on a cycle as a heat engine, a heat pump, or a refrigerator, depending on the objective of the particular device. If the objective of the device is to perform work it is a heat engine; if its objective is to transfer heat to a body it is a heat pump; if its objective is to transfer heat from a body, it is a refrigerator. Generically, a heat pump and a refrigerator are collectively referred to as a refrigerator. A schematic diagram of a simple heat engine is shown in Fig. 5.1.

An engine or a refrigerator operates between two thermal energy reservoirs, entities that are capable of providing or accepting heat without changing temperatures. The atmosphere and lakes serve as heat sinks; furnaces, solar collectors, and burners serve as heat sources. Temperatures T peratures of a source and a sink.and T identify the espective tem-The net work W produced by the engine of Fig. 5.1 in one cycle would be equal to the net heat transfer, a consequence of the first law [see Eq. (4.2)]:

where Q is the heat transfer to or from the high-temperature reservoir, and Q is the heat transfer to or from the low-temperature reservoir.

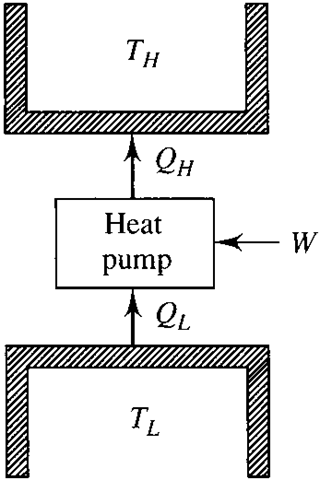

If the cycle of Fig. 5.1 were reversed, a net work input would be required, as shown in Fig. 5.2. A heat pump would provide energy as heat Q to the warmer ody (e.g., a house), and a refrigerator would extract energy as heat Q from the cooler body (e.g., a freezer). The work would also be given by Eq. (5.1), where we use magnitudes only.

Figure 5.1 A heat engine.

Figure 5.2 A refrigerator.

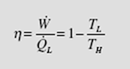

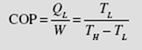

The thermal efficiency of the heat engine and the coefficients of performance (abbreviated COP) of the refrigerator and the heat pump are defined as follows:

where W is the net work output of the engine or the work input to the refrigerator. Each of the performance measures represents the desired output divided by the input (energy that is purchased).

The second law of thermodynamics will place limits on the above measures of performance. The first law would allow a maximum of unity for the thermal efficiency and an infinite coefficient of performance. The second law, however, establishes limits that are surprisingly low, limits that cannot be exceeded regardless of the cleverness of proposed designs.

One additional note: There are devices that we will refer to as heat engines that do not strictly meet our definition; they do not operate on a thermodynamic cycle but instead exhaust the working fluid and then intake new fluid. The internal combustion engine is an example. Thermal efficiency, as defined above, remains a quantity of interest for such engines.

5.2 Statements of the Second Law

As with the other basic laws presented, we do not derive a basic law but merely observe that such a law is never violated. The second law of thermodynamics can be stated in a variety of ways. Here we present two: the Clausius statement and the Kelvin-Planck statement. Neither is presented in mathematical terms. We will, however, provide a property of the system, entropy, which can be used to determine whether the second law is being violated for any particular situation.

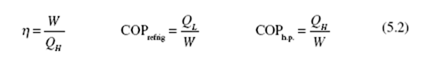

Clausius Statement It is impossible to construct a device that operates in a cycle and whose sole effect is the transfer of heat from a cooler body to a hotter body.

This statement relates to a refrigerator (or a heat pump). It states that it is impossible to construct a refrigerator that transfers energy from a cooler body to a hotter body without the input of work; this violation is shown in Fig. 5.3a.

Kelvin-Planck Statement It is impossible to construct a device that operates in a cycle and produces no other effect than the production of work and the transfer of heat from a single body.

In other words, it is impossible to construct a heat engine that extracts energy from a reservoir, does work, and does not transfer heat to a low-temperature reservoir.

This rules out any heat engine that is 100 percent efficient, like the one shown in Fig. 5.3b.

Note that the two statements of the second law are negative statements. They are expressions of experimental observations. No experimental evidence has ever been obtained that violates either statement of the second law. An example will demonstrate that the two statements are equivalent.

EXAMPLE 5.1

Show that the Clausius and Kelvin-Planck statements of the second law are equivalent.

Solution

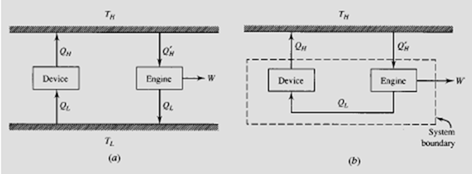

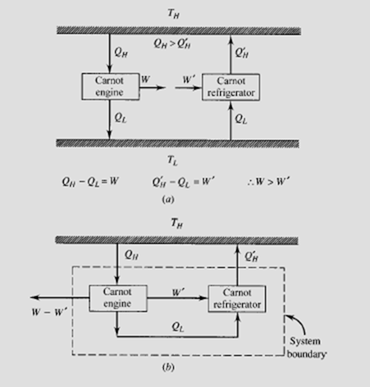

Consider the system shown. The device in (a) transfers heat and violates the Clausius statement, since it has no work input. Let the heat engine transfer the same

amount of heat QL. Then QH′ is greater than QL by the amount W. If we simply

transfer the heat Q directly from the engine to the device, as shown in (b), there is no need for the low-temperature reservoir and the net result is a conversion of energy (Q′ − Q ) from the high-temperature reservoir into an equivalent amount of work, a violation of the Kelvin-Planck statement of the second law. Conversely, a violation of the Kelvin-Planck statement is equivalent to a violation of the Clausius statement.

5.3 Reversibility

In our study of the first law we made use of the concept of equilibrium and we defined equilibrium, or quasiequilibrium, with reference to the system only. We must now introduce the concept of reversibility so that we can discuss the most efficient engine that can possibly be constructed; it is an engine that operates with reversible processes only: a reversible engine.

A reversible process is defined as a process which, having taken place, can be reversed and in so doing leaves no change in either the system or the surroundings. Observe that our definition of a reversible process refers to both the system and the surroundings. The process obviously has to be a quasiequilibrium process; additional requirements are:

1. No friction is involved in the process.

2. Heat transfer occurs due to an infinitesimal temperature difference only.

3. Unrestrained expansion does not occur.

The mixing of different substances and combustion also lead to irreversibilities, but the above three are the ones of concern in the study of the devices of interest.

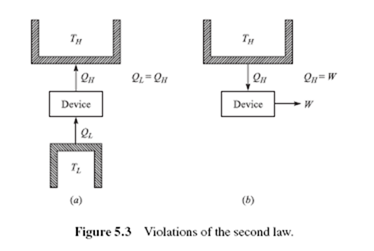

The fact that friction makes a process irreversible is intuitively obvious. Consider the system of a block on the inclined plane of Fig. 5.4a. Weights are added until the block is raised to the position shown in Fig. 5.4b. Now, to return the system to its original state some weight must be removed so that the block will slide back down the plane, as shown in Fig. 5.4c. Note that the surroundings have experienced a significant change; the removed weights must be raised, which requires a work input. Also, the block and plane are at a higher temperature due to the friction, and heat must be transferred to the surroundings to return the system to its original state. This will also change the surroundings. Because there has been a change in the surround- ings as a result of the process and the reversed process, we conclude that the process was irreversible. A reversible process requires that no friction be present.

To demonstrate the less obvious fact that heat transfer across a finite temperature difference makes a process irreversible, consider a system composed of two blocks, one at a higher temperature than the other. Bringing the blocks together results in a

Figure 5.4 Irreversibility due to friction.

heat transfer process; the surroundings are not involved. To return the system to its original state, we must refrigerate the block that had its temperature raised. This will require a work input, demanded by the second law, resulting in a change in the surroundings since the surroundings must supply the work. Hence, heat transfer across a finite temperature difference is an irreversible process. A reversible process requires that all heat transfer occur across an infinitesimal temperature difference so that a reversible process is approached.

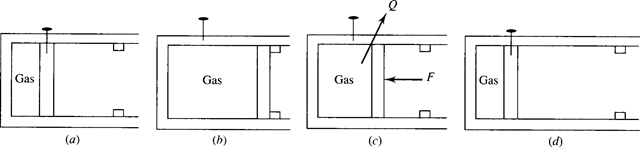

For an example of unrestrained expansion, consider the high-pressure gas contained in the cylinder of Fig. 5.5a. Pull the pin and let the piston suddenly move to the stops shown. Note that the only work done by the gas on the surroundings is to move the piston against atmospheric pressure. Now, to reverse this process it is necessary to exert a force on the piston. If the force is sufficiently large, we can move the piston to its original position, shown in Fig. 5.5d. This will demand a considerable amount of work to be supplied by the surroundings. In addition, the temperature will increase substantially, and this heat must be transferred to the surroundings to return the temperature to its original value. The net result is a significant change in the surroundings, a consequence of irreversibility. Unrestrained expansion cannot occur in a reversible process.

Figure 5.5 Unrestrained expansion.

5.4 The Carnot Engine

The heat engine that operates the most efficiently between a high-temperature reservoir and a low-temperature reservoir is the Carnot engine. It is an ideal engine that uses reversible processes to form its cycle of operation; thus it is also called a reversible engine. We will determine the efficiency of the Carnot engine and also evaluate its reverse operation. The Carnot engine is very useful, since its efficiency establishes the maximum possible efficiency of any real engine. If the efficiency of a real engine is significantly lower than the efficiency of a Carnot engine operating between the same limits, then additional improvements may be possible.

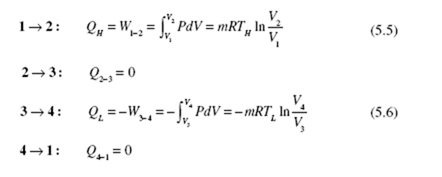

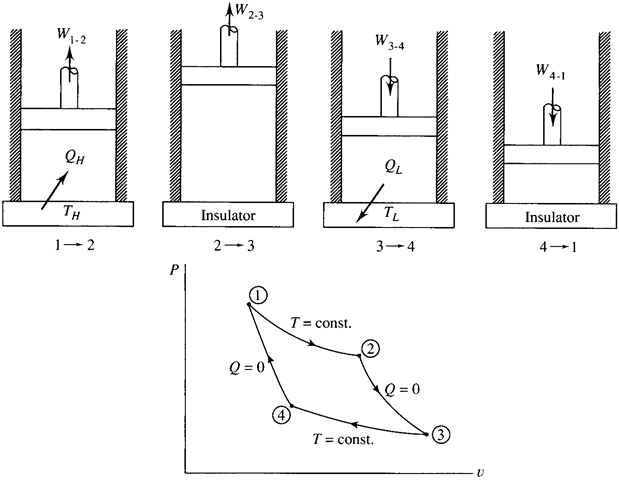

The cycle associated with the Carnot engine is shown in Fig. 5.6, using an ideal gas as the working substance. It is composed of the following four reversible processes:

1 → 2: Isothermal expansion. Heat is transferred reversibly from the

high-temperature reservoir at the constant temperature TH. The piston in the

cylinder is withdrawn and the volume increases.

Figure 5.6 The Carnot cycle.

2 → 3: Adiabatic reversible expansion. The cylinder is completely

insulated so that no heat transfer occurs during this reversible process. The

piston continues to be withdrawn, with the volume increasing.

3 → 4: Isothermal compression. Heat is transferred reversibly to the low temperature reservoir at the constant temperature T . The piston compresses the working substance, with the volume decreasing.

4 → 1: Adiabatic reversible compression. The completely insulated

cylinder allows no heat transfer during this reversible process. The piston

continues to compress the working substance until the original volume, temperature, and pressure are reached, thereby completing the cycle.

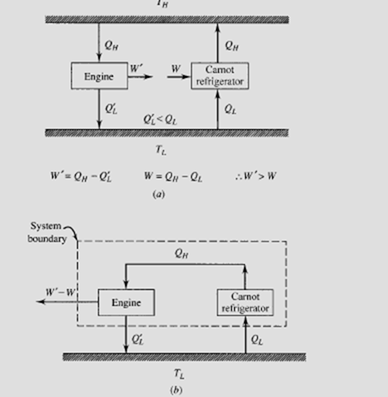

Applying the first law to the cycle, we note that

where Q is assumed to be a positive value for the heat transfer to the low-temperature

reservoir. This allows us to write the thermal efficiency [see Eq. (5.2)] for the Carnot cycle as

The following examples will be used to prove the following three postulates:

Postulate 1 It is impossible to construct an engine, operating between two given temperature reservoirs, that is more efficient than the Carnot engine.

Postulate 2 The efficiency of a Carnot engine is not dependent on the working substance used or any particular design feature of the engine.

Postulate 3 All reversible engines, operating between two given temperature reservoirs, have the same efficiency as a Carnot engine operating between the same two temperature reservoirs.

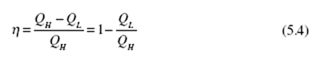

EXAMPLE 5.2

Show that the efficiency of a Carnot engine is the maximum possible efficiency.

Solution

Assume that an engine exists, operating between two reservoirs, that has an efficiency greater than that of a Carnot engine; also, assume that a Carnot

engine operates as a refrigerator between the same two reservoirs, as shown below. Let the heat transferred from the high-temperature reservoir to the engine be equal to the heat rejected by the refrigerator; then the work produced by the engine will be greater than the work required by the refrigerator (i.e., Q ′L < QL) since the efficiency of the engine is greater than that of a Carnot engine. Now, our system can be organized as shown in (b).The engine drives the refrigerator using the rejected heat from the refrigerator. But, there is some net work (W ′ − W) that leaves the system. The net result is the conversion of energy from a single reservoir into work, a violation of the second law. Thus, the Carnot engine is the most efficient engine operating between two particular reservoirs.

EXAMPLE 5.3

Show that the efficiency of a Carnot engine operating between two reservoirs is independent of the working substance used by the engine.

Suppose that a Carnot engine drives a Carnot refrigerator as shown in (a). Let the heat rejected by the engine equal the heat required by the refrigerator. Suppose the working fluid in the engine results in Q being greater than QH′ ; then

W would be greater than W′ (a consequence of the first law) and we would have the equivalent system shown in (b). The net result is a transfer of heat (Q − QH′ ) from a single reservoir and the production of work, a clear violation of the second law. Thus, the efficiency of a Carnot engine is not dependent on the working substance.

5.5 Carnot Efficiency

Since the efficiency of a Carnot engine is dependent only on the two reservoir temperatures, the objective of this article will be to determine that relationship. We will assume the working substance to be an ideal gas (refer to Postulate 2) and simply

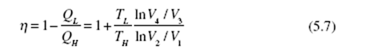

perform the required calculations for the four processes of Fig. 5.5. The heat trans- fer for each of the four processes is as follows: Note that we want Q to be a positive quantity, as in the thermal efficiency relation ship; hence, the negative sign. The thermal efficiency [Eq. (5.4)] is then

Note that we want Q to be a positive quantity, as in the thermal efficiency relation ship; hence, the negative sign. The thermal efficiency [Eq. (5.4)] is then

During the reversible adiabatic processes 2 → 3 and 4 → 1, we have

Substituting into Eq. (5.7), we obtain the efficiency of the Carnot engine (recognizing that lnV2 / V1 = − lnV1 / V2 ) :

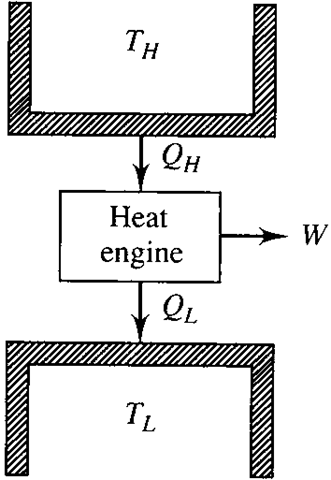

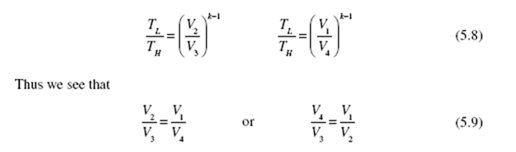

We have simply replaced Q /Q with T /T . We can make this replacement for L H L H all reversible engines or refrigerators. We see that the thermal efficiency of a Carnot engine is dependent only on the high and low absolute temperatures of the reservoirs. The fact that we used an ideal gas to perform the calculations is not important since we have shown that Carnot efficiency is independent of the working substance. Consequently, the relationship (5.10) is applicable for all working substances, or for all reversible engines, regardless of the particular design characteristics. The Carnot engine, when operated in reverse, becomes a heat pump or a refrigerator, depending on the desired heat transfer. The coefficient of performance for a Carnot heat pump becomes

The coefficient of performance for a Carnot refrigerator takes the form

The coefficient of performance for a Carnot refrigerator takes the form

The above measures of performance set limits that real devices can only approach.

The reversible cycles assumed are obviously unrealistic, but the fact that we have limits that we know cannot be exceeded is often very helpful.

EXAMPLE 5.4

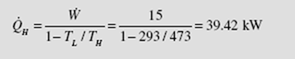

A Carnot engine operates between two temperature reservoirs maintained at 200 and 20°C, respectively. If the desired output of the engine is 15 kW, determine the Q·and Q· .

Solution

The efficiency of a Carnot engine is given by

This gives, converting the temperatures to absolute temperatures,

EXAMPLE 5.5

A refrigeration unit is cooling a space to −5°C by rejecting energy to the atmosphere at 20°C. It is desired to reduce the temperature in the refrigerated spac to −25°C. Calculate the minimum percentage increase in work required, by assuming a Carnot refrigerator, for the same amount of energy removed.

Solution

For a Carnot refrigerator we know that

For the first situation we have

Note the large increase in energy required to reduce the temperature in a refrigerated space. And this is a minimum percentage increase, since we have assumed an ideal refrigerator.

5.6 Entropy

To allow us to apply the second law of thermodynamics to a process we will identify a property called entropy. This will parallel our discussion of the first law; first we stated the first law for a cycle and then derived a relationship for a process.

Consider the reversible Carnot engine operating on a cycle consisting of the processes described in Sec. 5.5. The quantity ∫ δQ /T is the cyclic integral of the heat transfer divided by the absolute temperature at which the heat transfer occurs. Since the temperature T is constant during the heat transfer Q and T is constant during heat transfer Q , the integral is given by

where the heat Q leaving the Carnot engine is considered to be positive. Using Eqs. (5.4) and (5.10) we see that, for the Carnot cycle,

Substituting this into Eq. (5.13), we find the interesting result

Thus, the quantity δ Q/T is a perfect differential, since its cyclic integral is zero. We let this differential be denoted by dS, where S depends only on the state of the system. This, in fact, was our definition of a property of a system. We shall call this extensive property entropy; its differential is given by

where the subscript “rev” emphasizes the reversibility of the process. This can be integrated for a process to give

![]() From the above equation we see that the entropy change for a reversible process can be either positive or negative depending on whether energy is added to or extracted from the system during the heat transfer process. For a reversible adiabatic process (Q = 0) the entropy change is zero. If the process is adiabatic but

From the above equation we see that the entropy change for a reversible process can be either positive or negative depending on whether energy is added to or extracted from the system during the heat transfer process. For a reversible adiabatic process (Q = 0) the entropy change is zero. If the process is adiabatic but

irreversible, it is not generally true that ΔS = 0.

Figure 5.7 The Carnot cycle.

We often sketch a temperature-entropy diagram for cycles or processes of interest. The Carnot cycle provides a simple display when plotting temperature vs. entropy; it is shown in Fig. 5.7. The change in entropy for the first isothermal process from state 1 to state 2 is

The entropy change for the reversible adiabatic process from state 2 to state 3 is zero. For the isothermal process from state 3 to state 4 the entropy change is negative that of the first process from state 1 to state 2; the process from state 4 to state 1 is also a reversible adiabatic process and is accompanied with a zero entropy change.

The heat transfer during a reversible process can be expressed in differential form [see Eq. (5.16)] as

Hence, the area under the curve in the T–S diagram represents the heat transfer during any reversible process. The rectangular area in Fig. 5.6 thus represents the net heat transfer during the Carnot cycle. Since the heat transfer is equal to the work done for a cycle, the area also represents the net work accomplished by the system during the cycle. For this Carnot cycle Qnet = Wnet = ΔT ΔS.

The first law of thermodynamics, for a reversible infinitesimal change, becomes, using Eq. (5.19),

TdS − PdV = dU (5.20)

This is an important relationship in our study of simple systems. We arrived at it assuming a reversible process. However, since it involves only properties of the system, it holds for any process including any irreversible process. If we have an irreversible process, in eneral, δW ≠ PdV and δQ ≠ TdS but Eq. (5.20) still holds as a relationship between the properties since changes in properties do not depend on the process. Dividing by the mass, we have

Tds − Pdv = du (5.21)

where the specific entropy is s = S/m.

To relate the entropy change to the enthalpy change we differentiate the defini- tion of enthalpy and obtain

dh = du + Pdv + vdP (5.22)

Substituting into Eq. (5.21) for du, we have

Tds = dh – vdP (5.23)

Equations (5.21) and (5.23) will be used in subsequent sections of our study of thermodynamics for various reversible and irreversible processes.

ENTROPY FOR AN IDEAL GAS WITH CONSTANT SPECIFIC HEATS

Assuming an ideal gas, Eq. (5.21) becomes

where we have used du = Cv dT and Pv = RT . Equation (5.24) is integrated, assuming constant specific heat, to yield

Similarly, Eq. (5.23) is rearranged and integrated to give

Note again that the above equations were developed assuming a reversible process; however, they relate the change in entropy to other thermodynamic properties at the two end states. Since the change of a property is independent of the process used in going from one state to another, the above relationships hold for any process, reversible or irreversible, providing the working substance can be approximated by an ideal gas with constant specific heats.

If the entropy change is zero, as in a reversible adiabatic process, Eqs. (5.25) and (5.26) can be used to obtain

These are, of course, identical to the equations obtained in Chap. 4 for an ideal gas with constant specific heats undergoing a quasiequilibrium adiabatic process. We now refer to such a process as an isentropic process.

EXAMPLE 5.6

Air is contained in an insulated, rigid volume at 20°C and 200 kPa. A paddle wheel, inserted in the volume, does 720 kJ of work on the air. If the volume is 2m3, calculate the entropy increase assuming constant specific heats.

Solution

To determine the final state of the process we use the energy equation, assuming

zero heat transfer. We have −W = ΔU = mCv ΔT . The mass m is found from the

ideal-gas equation to be

The first law, taking the paddle-wheel work as negative, is then

Using Eq. (5.25) for this constant-volume process there results

EXAMPLE 5.7

After a combustion process in a cylinder the pressure is 1200 kPa and the temperature is 350°C. The gases are expanded to 140 kPa with a reversible adiabatic process. Calculate the work done by the gases, assuming they can be approximated by air with constant specific heats.

Solution

The first law can be used, with zero heat transfer, to give −w = Δu = Cv (T2 − T1 ). The temperature T is found from Eq. (5.27) to be

ENTROPY FOR AN IDEAL GAS WITH VARIABLE SPECIFIC HEATS

If the specific heats for an ideal gas cannot be assumed constant over a particular temperature range we return to Eq. (5.23) and write![]()

The gas constant R can be removed from the integral, but C removed. Hence, we integrate Eq. (5.28) and obtain

The integral in the above equation depends only on temperature, and we can evaluate its magnitude from the gas tables (given in App. E). It is found, using the tabulated function so from App. E, to be

Thus, the entropy change is (in some textbooks φ is used rather than so)

![image_thumb[23] image_thumb[23]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-r37Acl9LhR8/VFEX7mTTUNI/AAAAAAAAs4M/W3h3ebx80YE/image_thumb%25255B23%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800) This more exact expression for the entropy change is used only when improved accuracy is desired (usually for large temperature differences).

This more exact expression for the entropy change is used only when improved accuracy is desired (usually for large temperature differences).

For an isentropic process we cannot use Eqs. (5.25) and (5.26) if the specific heats are not constant. However, we can use Eq. (5.31) and obtain, for an isentropic process,

Thus, we define a relative pressure P , which depends only on the temperature, as

Pr = eso / R (5.33)

It is included as an entry in air table E.1. The pressure ratio for an isentropic process

is then

The volume ratio can be found using the ideal-gas equation of state. It is

where we would assume an isentropic process when using the relative pressure ratio. Consequently, we define a relative specific volume vr , dependent solely on the temperature, as![]()

Using its value from air table E.1 we find the specific volume ratio for an isentropic process; it is

With the entries from air table E.1 we can perform the calculations required when working problems involving air with variable specific heats.

EXAMPLE 5.8

Repeat Example 5.6 assuming variable specific heats.

Solution

Using the gas tables, we write the first law as −W = ΔU = m(u2 − u1 ). The mass

is found in Example 5.6 to be 4.76 kg. The first law is written as

where u is found at 293 K in air table E.1 by interpolation. Now, using this value o o for u2, we can interpolate to find T2 = 501.2 K and s2 = 2.222. The value for s1 is interpolated to be so = 1.678. The pressure at state 2 is found using the ideal-gas equation for our constant-volume process:

The approximate result of Example 5.6 is seen to be less than 0.3 percent in error. If T2 were substantially greater than 500 K, the error would be much more significant.

EXAMPLE 5.9

After a combustion process in a cylinder the pressure is 1200 kPa and the temperature is 350°C. The gases are expanded to 140 kPa in a reversible, adiabatic process. Calculate the work done by the gases, assuming they can be approximated by air with variable specific heats.

Solution

First, at 623 K the relative pressure Pr1 is interpolated to be

The approximate result of Example 5.7 is seen to have an error less than 1.5 percent. The temperature difference (T2– T1) is not very large; hence the small error.

ENTROPY FOR STEAM, SOLIDS, AND LIQUIDS

The entropy change has been found for an ideal gas with constant specific heats and for an ideal gas with variable specific heats. For pure substances, such as steam, entropy is included as an entry in the steam tables (given in App. C). In the quality region, it is found using the relation

Note that the entropy of saturated liquid water at 0°C is arbitrarily set equal to zero.

It is only the change in entropy that is of interest.

For a compressed liquid it is included as an entry in Table C.4, the compressed liquid table, or it can be approximated by the saturated liquid values s at the given temperature (ignoring the pressure). From the compressed liquid table at 10 MPa

and 100°C, s = 1.30 kJ/kg ⋅ K, and from the saturated steam table C.1 at 100°C, sf =

1.31 kJ/kg ⋅ K; this is an insignificant difference.

The temperature-entropy diagram is of particular interest and is often sketched

during the problem solution. A T-s diagram is shown in Fig. 5.8; for steam it is essentially symmetric about the critical point. Note that the high-pressure lines in the compressed liquid region are indistinguishable from the saturated liquid line. It is often helpful to visualize a process on a T–s diagram, since such a diagram illustrates assumptions regarding irreversibilities.

For a solid or a liquid, the entropy change can be found quite easily if we can assume the specific heat to be constant. Returning to Eq. (5.21), we can write, assuming the solid or liquid to be incompressible so that dv = 0,

Tds = du = CdT (5.39)

where we have dropped the subscript on the specific heat since for solids and liquids Cp ≅ Cv , such as Table B.4, usually list values for Cp; these are assumed to be

equal to C. Assuming a constant specific heat, we find that

If the specific heat is a known function of temperature, the integration can be per- formed. Specific heats for solids and liquids are listed in Table B.4.

EXAMPLE 5.10

Steam is contained in a rigid container at an initial pressure of 600 kPa and 300°C. The pressure is reduced to 40 kPa by removing energy via heat transfer. Calculate the entropy change and the heat transfer.

Solution

From the steam tables, v1 = v 2 = 0.4344 m /kg. State 2 is in the quality region. Using the above value for v 2 the quality is found as follows:

0.4344 = 0.0011 + x(0.4625 − 0.0011) ∴ x = 0.939

The entropy at state 2 is s2 = 1.777 + 0.939 × 5.1197 = 6.584 kJ/kg ⋅ K. The entropy change is then

Δs = s2 − s1 = 6.584 − 7.372 = − 0.788 kJ/kg ⋅ K

The heat transfer is found from the first law using w = 0 and u1 = 2801 kJ/kg:

q = u2 − u1 = (604.3 + 0.939 × 1949.3) − 2801 = – 366 kJ/kg

![image_thumb[1] image_thumb[1]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/--dRXKSldwIs/VFEWNs1J3RI/AAAAAAAAsu8/YwAL0jgfCWw/image_thumb%25255B1%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[2] image_thumb[2]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-3G6qi3iG76c/VFEWUHRJMQI/AAAAAAAAsvo/MNPnSaQNWxY/image_thumb%25255B2%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[3] image_thumb[3]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/-KnRbUy6x7ng/VFEWXCmUgMI/AAAAAAAAswE/EkcFCS5QkeE/image_thumb%25255B3%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[5] image_thumb[5]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/-vcE4iX8OC6E/VFEWes7yaOI/AAAAAAAAsw8/A9Y4hL2MJRA/image_thumb%25255B5%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[8] image_thumb[8]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/-ZwL5ci9Fnbk/VFEWmbynLjI/AAAAAAAAsx8/meXLTu3J97w/image_thumb%25255B8%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[9] image_thumb[9]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/-VgkdAXy6RTw/VFEWqc7hCMI/AAAAAAAAsyY/sCFicXmRpZw/image_thumb%25255B9%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[12] image_thumb[12]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/-f4R2hp84Ybo/VFEW0Wl6tqI/AAAAAAAAszc/cesLyLtjm7o/image_thumb%25255B12%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[14] image_thumb[14]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/-gI5kZpnizyw/VFEXCQ3lzdI/AAAAAAAAs0Y/AJqH2vTU9Z4/image_thumb%25255B14%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[15] image_thumb[15]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/-1lJ0x4IcFqY/VFEXMpcczdI/AAAAAAAAs08/zj8gdyiwGc8/image_thumb%25255B15%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[16] image_thumb[16]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-BSVFTsXCW8k/VFEXR9OuSbI/AAAAAAAAs1Y/PBa-DSORa7Y/image_thumb%25255B16%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[17] image_thumb[17]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/-HtJurjxJLFE/VFEXY2w3mAI/AAAAAAAAs10/pEU5PSygJ-8/image_thumb%25255B17%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[19] image_thumb[19]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-uNw4dUBdRlM/VFEXldAM_-I/AAAAAAAAs2w/0JrEUadJi7o/image_thumb%25255B19%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[22] image_thumb[22]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/-34PQcZvVts4/VFEX3PyLZJI/AAAAAAAAs38/aeStyNvCV6c/image_thumb%25255B22%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[24] image_thumb[24]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/-UKrxITzcAjg/VFEX_K2QL_I/AAAAAAAAs4c/BubHceo78BA/image_thumb%25255B24%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[25] image_thumb[25]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/-6KBH4V_Qnmo/VFEYCYqip1I/AAAAAAAAs4s/SnjfYMkAqxs/image_thumb%25255B25%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[26] image_thumb[26]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-evMtFZ_z0xI/VFEYF6fq1LI/AAAAAAAAs48/A60-NgYz1zQ/image_thumb%25255B26%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[28] image_thumb[28]](http://lh3.ggpht.com/-EBuXyrx3tPI/VFEYNclQ5GI/AAAAAAAAs5c/QtIUNMXVNVQ/image_thumb%25255B28%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[29] image_thumb[29]](http://lh4.ggpht.com/-2ZYmSX2Pgs0/VFEYR1GPqvI/AAAAAAAAs5s/EP_7ua5FNAw/image_thumb%25255B29%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[30] image_thumb[30]](http://lh5.ggpht.com/-5BeRxUu9BX4/VFEYV1LAGnI/AAAAAAAAs58/z3i7jzIXkjM/image_thumb%25255B30%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[31] image_thumb[31]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/-19_h4zIBVk8/VFEYbDS4aAI/AAAAAAAAs6M/zSeAtVctXsY/image_thumb%25255B31%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)

![image_thumb[33] image_thumb[33]](http://lh6.ggpht.com/-IqzLKDJAw-s/VFEYkMdwOKI/AAAAAAAAs6s/fUmmeNqakzg/image_thumb%25255B33%25255D_thumb.png?imgmax=800)