age-related macular degeneration (ARMD) A progressive condition that results in the gradual deterioration of the macula, the portion of the RETINA that provides the ability to see fine detail, and loss of vision from the center of the field of vision. ARMD is the leading cause of VISION IMPAIR- MENT, resulting in functional limitations and legal blindness in people over the age of 50. ARMD develops when the retina’s BLOOD supply diminishes. The macula’s high concentration of cones, the cells responsible for color and fine detail vision, makes it especially vulnerable to damage and its cells begin to die. The death of the cells result in diminished vision. ARMD may affect one eye at first, though nearly always affects both eyes as it progresses.

There are two forms of ARMD, atrophic (commonly known as dry) and neovascular (commonly known as wet). All ARMD begins as the atrophic form, in which the nourishing outer layer of the retina withers, or atrophies. Approximately 90 percent of ARMD remains in this form and progresses slowly. In the remaining 10 percent, new blood vessels begin to grow erratically within the choroid, the blood-rich membrane that nourishes the retina. These blood vessels are thin and fragile, and bleed easily. The resulting hemorrhages cause the retina to swell, distorting the macula and accelerating the loss of cells.

Symptoms and Diagnostic Path

ARMD begins insidiously and people tend to attribute early symptoms to the normal changes of aging. Early symptoms include

• blurring of words when reading

• “missing pieces” in the field of vision, such as parts of words or gaps in the appearance of lines or objects

• the need for increased light to perform tasks that require close vision

• faded colors

• tendency to look slightly to the side of objects to see them clearly

• distorted or wavy lines on linear objects such as signs, doorways, and railings (suggests wet ARMD)

As the macular degeneration progresses, a blind spot in the center of vision becomes apparent and enlarges. Wet ARMD progresses far more rapidly than dry ARMD. A simple screening test called the AMSLER GRID can show the gaps in vision that occur with either form of ARMD. The ophthalmologist uses further procedures, such as OPHTHAL- MOSCOPY and SLIT LAMP EXAMINATION, to visualize the retina and macula and determine which form of ARMD is present and how extensive the damage. The ophthalmologist looks for signs of exudation (swelling of the tissue that oozes fluid) that suggests wet ARMD, and for drusen (spots of depigmentation on the macula that signal the loss of retinal cells). For wet ARMD, the ophthalmologist may perform a diagnostic procedure called fluorescein angiography, in which the ophthalmologist injects fluorescein dye into a VEIN and then takes photographs of the retina as the dye flows through its blood vessels.

Treatment Options

Treatment options for ARMD are limited, and at this time there really are no treatments for dry ARMD. Some research studies demonstrate the rate of degeneration slows with increased consumption of the antioxidants lutein and zeaxanthin, and vitamins A, C, and E. For wet ARMD the laser treatments photocoagulation and photodynamic therapy are sometimes effective in sealing bleeding blood vessels and thwarting their growth, though they cannot permanently halt the neovascularization or restore vision already lost. Photo- coagulation uses a hot laser to cauterize the blood vessels but also destroys cells in the vicinity of the targeted blood vessels. With photodynamic therapy, the ophthalmologist injects a photosensitive DRUG into the person’s veins, then uses a cool laser to target blood vessels in the retina when the drug reaches them. The light of the laser is not intense enough to burn the tissue though activates the drug, which then destroys the blood vessels.

Outlook and Lifestyle Modifications

For most people who have ARMD vision declines slowly and may affect only one eye for a long time before affecting the other eye as well. Because the loss affects the center of the field of vision, vision loss is not complete though affects activities that require detailed focus, such as reading and driving, and typically reaches the level of legal blind- ness. Numerous community and health-care resources can assist with adaptive methods to accommodate diminishing vision. Even with wet ARMD, which progresses more rapidly and more severely than dry ARMD, some vision remains.

Causes and Preventive Measures Researchers do not know what causes ARMD, though it appears to have a hereditary component in that it runs in families. There are few treatments, and there is no cure, though there is evidence that antioxidants slow the rate of deterioration and the loss of vision. Vision loss is permanent. As yet there are no known measures to prevent ARMD. It appears that ARMD is more common in people who:

• smoke cigarettes

• have blue or green eyes

• experience extensive exposure to ultraviolet rays, as in sunlight exposure

• have CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE (CVD) such as HYPERTENSION (high blood pressure), ATHEROSCLE- ROSIS, or CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE (CAD)

People who have more than one risk factor, especially when one of the risk factors is family history, should frequently and regularly monitor their vision using the Amsler grid. Early diagnosis is particularly important with wet ARMD, for which limited treatment options exist. ARMD develops in people over age 50. An ophthalmologist should evaluate changes that alter the field of vision, especially those that take the form of distortions or “missing pieces.” Regular ophthalmic examinations are important to detect ARMD as well as other conditions that affect the eye and vision with advancing age.

See also AGING, VISION AND EYE CHANGES THAT OCCUR WITH; HEMORRHAGE; OPHTHALMIC EXAMINATION; RETINAL DETACHMENT; VISION HEALTH.

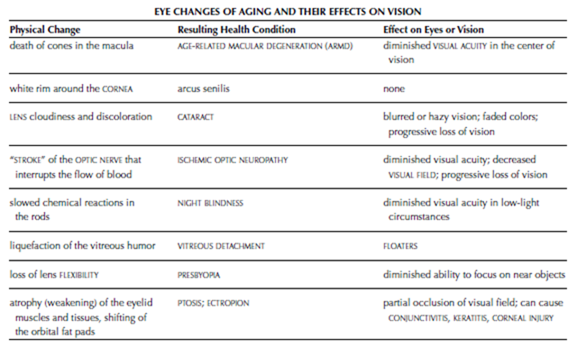

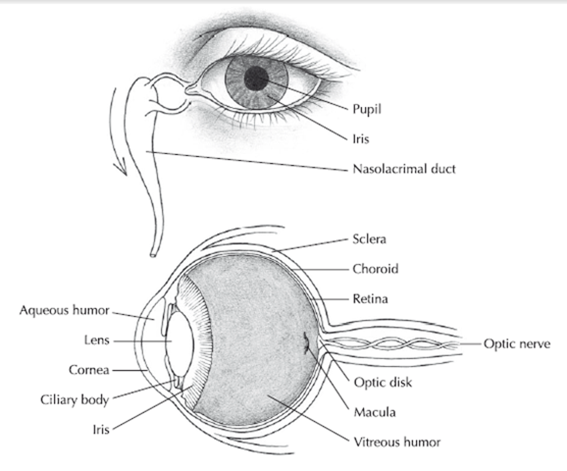

aging, vision and eye changes that occur with The structures of the EYE and the processes of vision begin to undergo changes in the late fourth or early fifth decade of life. By age 65, 50 percent of people have vision impairments. By age 80, more than 90 percent of people have vision impairments. Treatment can mitigate some of these changes, such as PRESBYOPIA and CATARACT. Some conditions that affect the eye and vision develop secondary to other health conditions that are more prevalent in older people, such as DIA- BETES, HYPERTENSION, and KIDNEY disease, all of which can cause RETINOPATHY. Much loss of vision related to aging is progressive and permanent, interfering with activities such as driving, reading and other close work, and seeing at night. How- ever, most people retain the ability to see well enough to function in everyday activities.

Adaptations to accommodate the changes of the eye and vision with aging are numerous and can help maintain a desirable QUALITY OF LIFE for many people. CORRECTIVE LENSES or reading glasses are effective for presbyopia. Surgery can improve vision impairments such as cataract (CATARACT EXTRACTION AND LENS REPLACEMENT), corneal damage (corneal reshaping or CORNEAL TRANSPLANTATION), and PTOSIS and ECTROPION (BLEPHAROPLASTY). Magni-

fiers for reading and close work, adjustments on televisions and computers to enlarge screen images, voice-activated telephone dialers, high- intensity light sources, and screen readers with voice output are among the devices available to accommodate low vision.

See also GENERATIONAL HEALTH-CARE PERSPECTIVES; VISION HEALTH.

amblyopia A VISION IMPAIRMENT, commonly called “lazy eye,” in which the pathways between the EYE and the BRAIN do not properly handle the processes of sight. Amblyopia is most common in children. The impairment often develops when there are circumstances that allow one eye to become dominant in sending NERVE impulses to the brain, such as STRABISMUS (the inability of the eyes to focus on the same object) or congenital cataracts (opacity of the lens). Amblyopia can also develop when there is significant disparity in the refractive capabilities of the eyes, such as when one eye is hyperopic (farsighted) or myopic (near- sighted) and the other eye has normal vision. The brain becomes accustomed to messages the dominant eye and “ignores” nerve signals from the nondominant, or “lazy,” eye. Untreated amblyopia can result in permanent vision impairment or legal blindness.

The diagnostic path includes close examination of the eyes to determine whether other disease processes are present that might account for the vision deficit. Treatment targets those processes, such as cataracts or REFRACTIVE ERRORS, when they exist. When the eye is otherwise healthy and nor- mal, treatment consists of forcing the brain to rely on the amblyopic eye, usually by patching the dominant eye for structured periods of time. Sometimes the ophthalmologist will substitute atropine drops in the eye, which dilate the pupil and distort the eye’s ability to focus, when a child refuses to wear an eye patch or an eye patch is otherwise not the most appropriate therapeutic choice. The dilation interferes with the eye’s ability to focus, forcing the brain to interpret nerve messages from the untreated eye.

When detected and treated in children who are under age 9, most amblyopia responds to treatment and vision returns. Delayed or inadequate treatment may result in permanent dysfunction of the eye–brain pathways, as these become entrenched by age 9 or 10. After this time the vision pathways are well established and amblyopia can no longer develop.

See also ASTIGMATISM; HYPEROPIA; MYOPIA; PTOSIS.

Amsler grid A basic test to detect or monitor the progression of AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION (ARMD), a condition in which the macula, the area on the RETINA responsible for fine detail vision, deteriorates. The Amsler grid is a square with evenly spaced horizontal and vertical lines, and a dot in the center of the grid. The grid’s four corners and lines should appear visible, straight, and intact. Wavy lines, gaps in the lines, or missing segments suggest damage to the macula. Such a result requires further examination from an ophthalmologist who specializes in retinal disorders.

See also VISUAL ACUITY.

astigmatism A common refractive error of vision that results from an irregularly shaped CORNEA.

Astigmatism may affect one EYE or both eyes. Typically the irregularity results in two focal points of light that reach the RETINA instead of a single focal point, resulting in blurred or distorted images. Astigmatism often coexists with HYPEROPIA (far- sightedness) or MYOPIA (nearsightedness) and tends to run in families. Corrective measures include eyeglasses, contact lenses, and REFRACTIVE SURGERY. Mild astigmatism may not produce noticeable vision disturbances, in which case it does not require correction. The success of corrective measures depends on the extent and nature of the corneal irregularities. Astigmatism often accompanies age-related changes in the eyes and vision, and is a common SIDE EFFECT of CORNEAL TRANSPLANTATION.

Less commonly astigmatism results from irregularities in the surface of LENS, called lenticular astigmatism. Options to correct for lenticular astigmatism are CORRECTIVE LENSES or lens-replacement surgery to implant an intraocular lens.

See also CATARACT EXTRACTION AND LENS REPLACE- MENT; REFRACTION TEST; REFRACTIVE ERRORS.