cataract Cloudiness and discoloration of the LENS. Cataracts become increasingly common with advancing age, affecting half of all people age 80 and older. Cataracts were once a leading cause of age-related blindness. Today ophthalmologists surgically remove cataracts and replace the lens with a prosthetic intraocular lens (IOL) that restores vision.

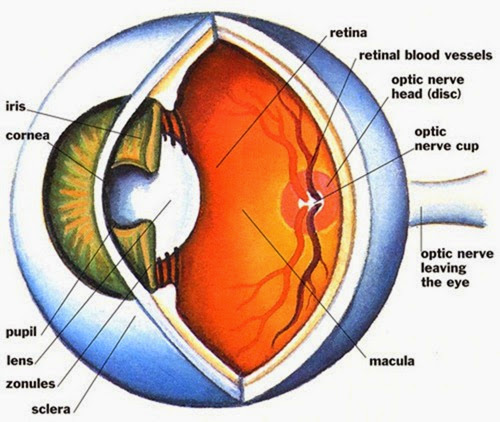

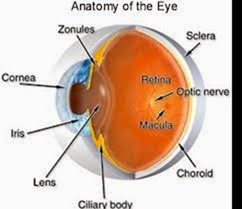

Cataracts result from protein deposits that accumulate within the lens. These deposits disperse light in much the same way cracks in a window might splinter sunlight shining through. The fragmented light creates areas of accentuated bright- ness, causing the halos and sensitivity to lights at night. The opacity of the cataract interferes with the refractive function of the lens, causing blurry or hazy vision. The yellow or gray discoloration of the lens common with mature or “ripe” cataracts filters the lightwaves that enter the EYE, particularly affecting those in the spectrum of blue. The location of the cataract on the lens determines the nature and extent of VISION IMPAIRMENT.

Age-related cataracts Most cataracts develop as a function of aging. Protein structures within the body, including the lens of the eye, begin to change. The lens becomes less resilient. Such changes make it easier for proteins to clump together, forming areas of opacity that eventually form cataracts. Nuclear cataracts form in the nucleus (gelatinous center) of the lens and are the most common type of age-related cataract. Corti- cal cataracts form in the cortex, or outer layer, of the lens and often do not affect vision.

Congenital cataracts Infants may be born with cataracts. A congenital cataract affecting only one eye typically is idiopathic (without identifiable cause); congenital cataracts affecting both eyes

often suggest genetic disorders such as DOWN SYN- DROME. A congenital cataract that is in the line of vision (on the visual axis) can cause significant vision impairment or blindness because the path- ways for vision develop in the infant’s first few months of life. Ophthalmologists usually remove such cataracts as soon as possible. Other congeni- tal cataracts may be small and located so they are inconsequential to vision; ophthalmologists generally take an approach of watchful waiting with these.

Cataracts of diabetes GLUCOSE, which can be present in high blood levels with DIABETES, inter- acts with the protein structure of the lens, causing protein clumping. People who have type 1 (INSULIN-dependent) diabetes are at greatest risk for cataracts of diabetes, which often develop at a young age. People who have type 2 diabetes or insulin resistance also are at increased risk. Developing cataracts account in part for the vision disturbances that are among the symptoms of diabetes. Treatment for cataracts of diabetes is the same as for age-related cataracts.

Symptoms and Diagnostic Path

Because cataracts develop slowly, symptoms become gradually noticeable. Symptoms usually affect only one eye (though cataracts may develop concurrently in both eyes) and may include

• blurry or hazy vision

• double vision

• halos around lights at night

• difficulty seeing at night

• colors appearing faded or dull, or difficulty perceiving shades of blue and purple

Gradual loss of vision at middle age and beyond may be a symptom of AGE- RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION (ARMD) or GLAUCOMA. Untreated, these conditions result in significant and permanent vision impairments. Any decrease in vision requires an ophthalmologist’s or optometrist’s prompt evaluation.

The ophthalmologist can see cataracts during OPHTHALMOSCOPY, a painless procedure for examining the interior of the eye.

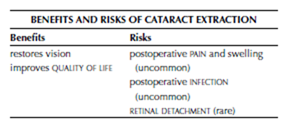

Treatment Options and Outlook

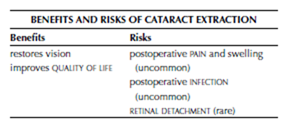

CATARACT EXTRACTION AND LENS REPLACEMENT is the treatment of choice for nearly all cataracts. There is no element of time-sensitivity for the surgery. Though VISUAL ACUITY will progressively deteriorate as the cataract enlarges, there is no permanent harm to vision by waiting to extract the cataract. Following cataract surgery, more than 90 percent of people experience vastly improved vision. Some people who are unable to receive an IOL because of other eye conditions will need to wear a special contact lens or eyeglasses to carry out the refractive functions of the extracted lens. Nearly every- one will still need reading glasses to accommodate PRESBYOPIA.

Risk Factors and Preventive Measures Cataracts are primarily a consequence of aging. Cataracts also can develop as a SIDE EFFECT of long- term STEROID use (therapeutic or performance enhancing). Cigarette smoking, excessive ALCOHOL consumption, and extended exposure to sunlight (ultraviolet rays) are among the lifestyle factors associated with early or accelerated cataract development. There are no known methods for pre- venting cataracts. See also AGING, EYE AND VISION CHANGES THAT OCCUR WITH; ANABOLIC STEROIDS AND STEROID PRECUR- SORS; CORTICOSTEROID MEDICATIONS; SMOKING AND HEALTH.

stage of its development. The vast majority of people who undergo cataract extraction fully recover without complications and experience VISUAL ACU- ITY correctable to 20/40 or better.

Surgical Procedure

Cataract extraction is nearly always an outpatient surgery performed under local anesthetic and a mild general sedative for comfort. There are three surgical procedures for cataract extraction. Each takes 20 to 30 minutes for the ophthalmologist to complete. Many variables influence the ophthalmologist’s choice for which to use.

Phacoemulsification The most commonly per- formed cataract extraction procedure is phacoemulsification, which requires a tiny incision into the capsule containing the lens. The ophthalmologist first uses ULTRASOUND to liquefy the central nucleus (inner, gelatinous portion of the lens) and then uses aspiration to remove it. Last the ophthalmologist removes the cortex (outer layer of the lens) from the capsule in multiple segments.

Extracapsular cataract extraction The extra- capsular cataract extraction procedure requires a slightly larger incision in the capsule, through which the ophthalmologist removes the central nucleus of the lens intact, then removes the cortex in multiple segments.

Lens replacement After extracting the cataract, the ophthalmologist inserts either a monofocal or multifocal IOL to give the eye the ability to focus. Contemporary lens designs allow the ophthalmologist to fold the lens, insert it into the lens capsule through the tiny incision used to extract the cataract, and unfold the IOL to place it in position.

Risks and Complications

Most ophthalmologists prescribe antibiotic and anti-inflammatory eye drops applied to the eye for four to six weeks following surgery, and recommend wearing dark glasses in bright light to help protect the eye from light sensitivity. Swelling and irritation of the tissues around the operated eye is normal in the first few weeks following surgery. Clear vision may take four to six weeks, though many people experience dramatic improvement immediately. Though the short-term risks of cataract extraction and lens replacement are minor, RETINAL DETACHMENT can occur months to years following surgery.

Cataract extraction is a permanent solution for cataracts. Once removed, cataracts cannot grow back. Some people do develop a complication called posterior capsule opacity, in which the membrane behind the IOL becomes cloudy (opaque). This is a complication that results when residual cells that remain after removal of the lens begin to grow across the membrane, causing the membrane to thicken. A follow-up procedure, either yttrium-aluminum-garnet (YAG) laser cap- sulotomy or conventional surgery, is necessary to remove the membrane.

Outlook and Lifestyle Modifications

About 90 percent of people experience vastly improved vision after cataract extraction. How- ever, other eye problems or underlying conditions (such as RETINOPATHY of diabetes) can affect the quality of vision. Many people do need eyeglasses after cataract extraction, as the IOL does not adjust for focus as does a natural lens. It is important to see the ophthalmologist for follow-up and routine eye care as recommended.

See also AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION (ARMD); BULLOUS KERATOPATHY; HYPEROPIA; MYOPIA; PRESBYOPIA; SMOKING AND HEALTH; SURGERY BENEFIT AND RISK ASSESSMENT.

chalazion A painless, hard nodule that arises from a gland (meibomian or sebaceous) along the edge of the eyelid, the result of glandular secretions that granulate. A chalazion may extend deep into the structure of the eyelid. A chalazion some- times forms at the site of a recurrent HORDEOLUM (an infected eyelid SEBACEOUS GLAND, also called a stye). Often a small chalazion will go away on its own, without treatment. Moist heat applied to the eyelid helps dissolve the granulated material and draw it from the gland. Because of the risk of scar-

ring and pain, the ophthalmologist may recommend excising (surgically removing) a chalazion that does not go away or that recurs. The procedure, with local anesthetic to numb the eyelid, takes only a few minutes in the doctor’s office. The wound typically heals within two weeks and leaves no scarring. Inflammatory skin conditions such as DERMATITIS or ROSACEA can block the eye- lid’s glands, causing a chalazion to develop. Care- ful eyelid hygiene helps keep secretions from accumulating.

See also BLEPHARITIS; CONJUNCTIVITIS; OPERATION.

cicatricial pemphigoid An autoimmune disorder in which painful blisters form on the inner surfaces of the eyelids (and may form on other mucus membranes, such as in the MOUTH and NOSE). SCAR tissue that forms after the blisters heal continues to irritate the inner eyelids as well as the outer surface of the EYE (sclera and CORNEA). The blisters commonly involve the lacrimal (tear) glands and ducts, reducing tear production and causing DRY EYE SYNDROME. Cicatricial pemphigoid occurs when the body’s IMMUNE SYSTEM produces antibodies that attack the cells that form the mucus membranes. Trauma appears to activate the eruptions of blisters and may be as inconsequential as rubbing the eye or the irritation such as occurs with exposure to environmental particulates such as pollen and dust. Some people first experience outbreaks of cicatricial pemphigoid following eye operations such as CATARACT EXTRACTION AND LENS REPLACEMENT or BLEPHAROPLASTY.

The diagnostic path includes laboratory tests to assess the levels of antibodies in the blood, particularly IMMUNOGLOBULIN G (IGG) and IMMUNOGLOBIN A

(IGA), the antibodies most closely associated with cicatricial pemphigoid. Treatment focuses on reducing BLISTER formation and minimizing scar- ring, typically by taking oral CORTICOSTEROID MED- ICATIONS or IMMUNOSUPPRESSIVE MEDICATIONS. As with

other AUTOIMMUNE DISORDERS, cicatricial pemphigoid tends to be chronic and recurrent. The persistent irritation can result in damage to the cornea that causes VISUAL IMPAIRMENT and, when severe, results in blindness.

See also ANTIBODY; CONJUNCTIVITIS; CORNEAL TRANSPLANTATION; ECTROPION; HUMAN LEUKOCYTE ANTI- GEN (HLA).

color deficiency A VISION IMPAIRMENT in which the ability to distinguish certain, and rarely all, colors is impaired. Color deficiency represents a shortage of normal cones, the specialized cells on the RETINA that detect color. Cones contain photo- sensitive chemicals that react to red, green, or blue. The most common presentation of color deficiency, accounting for about 98 percent of color deficiency, is red/green deficiency, in which the person cannot distinguish red and green. A small percentage of people cannot distinguish blue and yellow. Rarely, a person sees only in shades of gray.

Color perceptions occur when lightwaves of certain frequencies (lengths) activate the photo- chemicals in cones that are sensitive to the fre- quency. The BRAIN interprets the varying intensities and blends of the photochemical responses. Color deficiency occurs when the cones that perceive one of the three primary colors (red, green, blue) do not function properly.

The most common test for color vision and color deficiency is a series of disks that contain dots of color in random patterns with a structured pattern of differing color within the field. The structured pattern may be a number (most commonly) or an object. There is no treatment to compensate for color deficiency. People who are color-deficient learn to accommodate the deficiency through mechanisms such as memorizing the locations of colored objects (such as the sequence of lights in a traffic signal) and by making adaptations in their personal environments. A person may have friends or family members sort clothing by color, for example, and label the color groups. Some people who have mild color deficiency experience benefit from devices such as colored glasses and colored contact lenses that filter the lightwaves that enter the EYE. A yellow tint may improve blue-deficient color vision, for example.

Most color deficiency is an X-linked genetic MUTATION, affecting about 8 percent of men and 1⁄2 percent of women. Color deficiency may also develop with AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION (ARMD), RETINOPATHY, neurologic disorders such as MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS, and HEAVY-METAL POISONING such as lead or mercury. Antimalarial drugs can cause permanent changes in the RETINA that affect color vision; the ERECTILE DYSFUNCTION medication sildenafil (Viagra) can temporarily intensify the perception of blue.

See also VISION HEALTH; VISUAL ACUITY.

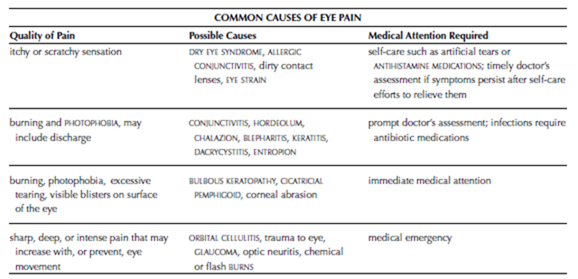

conjunctivitis An INFLAMMATION of the conjunctiva, or mucous tissue that lines the inside of the eyelids. There are many causes for conjunctivitis, commonly called pink EYE, including INFECTION (bacterial, viral, or fungal) and contact contamination such as due to pollen or substances in the air or on the fingers that irritate the tissues. Infectious conjunctivitis is highly contagious and very common, especially in children. Symptoms include

• red, swollen conjunctiva and sclera (inner eye- lids and the “white” of the eye)

• itchy or scratchy sensation

• thick, yellowish discharge that crusts

• PHOTOPHOBIA (sensitivity to light)

The doctor can usually diagnose conjunctivitis from its appearance. Typical treatment is application of an antibiotic medication in ophthalmic preparation (drops or ointment). Most conjunctivitis dramatically improves with 48 hours of initiating treatment, though symptoms may resolve gradually over 10 to 14 days, and does not require further medical attention. The doctor may culture the discharge when there is reason to suspect CHLAMYDIA or GONNORHEA is the cause, or when symptoms do not improve with treatment. Warm, moist compresses help relieve discomfort and clear away the discharge. Frequent HAND WASHING helps prevent spreading the infection. Untreated conjunctivitis, particularly when chlamydia or gonorrhea is the infectious agent, can cause permanent damage to the CORNEA, which results in VISUAL IMPAIRMENT or blindness.

See also ALLERGIC CONJUNCTIVITIS; ANTIBIOTIC MED- ICATIONS; BACTERIA; FUNGUS; SEXUALLY TRANSMITTED DISEASE (STD) PREVENTION; VIRUS.

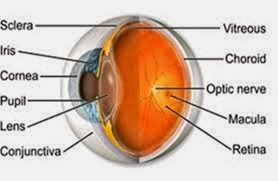

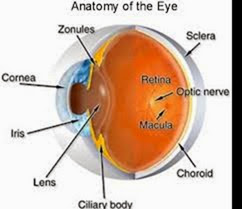

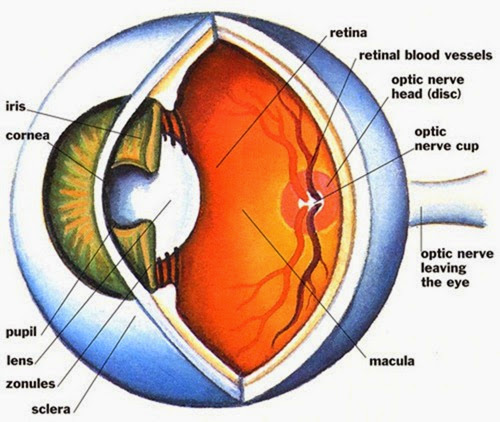

cornea The transparent portion of the sclera, the EYE’s outer layer. The cornea functions as a window to allow light to enter the eye and is the first point of refraction (bending lightwaves to focus them on the RETINA). Irregularities in the surface of the cornea can distort refraction, resulting in ASTIGMATISM. Though the cornea has no BLOOD vessels it has numerous NERVE endings that make it highly sensitive. Because it is the outermost portion of the eye, the cornea is also highly vulnerable to injury.

For further discussion of the cornea within the context of ophthalmologic structure and function please see the overview section “The Eyes.”

See also CORNEAL INJURY; CORNEAL TRANSPLANTA- TION; LENS; REFRACTIVE ERRORS.

corneal injury Lacerations, punctures, and blunt trauma to the CORNEA. Because of its position, somewhat protruding at the front of the EYE, the cornea is at risk for damage that can jeopardize vision.

Corneal injuries require immediate medical attention. Any puncture or penetrating wound to the eye is a medical emergency. Loosely patch both eyes to minimize eye movement

Dust, dirt, pollen, and other particulates in the air can scratch the surface of the cornea. Particles that adhere to the inside of the upper eyelid or objects that slash across the cornea before the eye- lid reflexively closes may cause lacerations (cuts) to the cornea. Though the cornea has no blood vessels and thus cannot bleed, it has numerous nerve endings that unmistakably sound the alert when injury occurs. Injury to the cornea also can diminish VISUAL ACUITY. Puncture or penetrating injuries can destroy the cornea and expose the inner eye to traumatic damage as well as INFECTION. Even minor ABRASIONS and lacerations can cause temporary vision impairment as well as present the risk for infection. Loss of the eye is possible when a significant penetrating wound allows the inner contents of the eye to escape.

Symptoms of corneal injury include

• discomfort ranging from a scratchy sensation to frank PAIN

• PHOTOPHOBIA (sensitivity to light)

• excessive tearing

• inability to keep the eye open

• blurred or distorted vision

The ophthalmologist can identify a corneal injury with FLUORESCEIN STAINING, a simple and pain- less procedure. Any areas of injury on the cornea absorb the fluorescein dye, causing them to glow green under blue light. Serious injuries to the cornea, or embedded foreign objects, may require immediate surgery to minimize loss of vision. Treatment for injuries that affect only the surface of the cornea may include ophthalmic ANTIBIOTIC MED- ICATIONS (drops or ointment) and patching of the affected eye. Protective eyewear, worn whenever there is the potential for particles or objects to strike the eye, helps prevent corneal injuries.

See also CORNEAL TRANSPLANTATION; TRAUMA TO THE EYE.

corneal transplantation The replacement of a Corneal injuries require immediate medical attention. Any puncture or penetrating wound to the eye is a medical emergency. Loosely patch both eyes to minimize eye movement.

diseased CORNEA with a healthy donor cornea. In the United States, ophthalmologists perform more than 45,000 corneal transplantations each year; up to 90 percent of people who receive trans- planted corneas experience restored vision; success depends on the reason for the transplant. Ophthalmologists may recommend corneal trans- plantation to treat:

• BULLOUS KERATOPATHY

• KERATOCONUS

• KERATITIS

• significant CORNEAL INJURY

Donor corneas are harvested within a few hours of death and can be preserved for up to 14 days. Current practice does not employ blood type or tissue type matching for corneal transplantation, though some studies suggest matching the blood type of donor and recipient reduces the risk for rejection.

CORNEA DONATION

Nearly anyone can donate his or her corneas after death. There is no cost to the donor. An eye bank coordinates the harvesting, testing, storage, and dispensing of donated corneas. Many states incorporate organ donor authorization with driver’s licenses. People should tell family members that they wish to donate their corneas.

Corneal transplantation surgery takes place with a local anesthetic to numb the eye and an intravenous sedative medication for relaxation and comfort. The operation takes 45 to 60 minutes. From the donor cornea, the ophthalmologist uses a trephine, a device that cleanly punches out a buttonlike segment of the cornea’s center. Using a surgical microscope, the ophthalmologist then removes a similarly shaped segment from the dis- eased cornea and places the donor button in its place. Very fine suture, sometimes thinner than a human hair, secures the donor corneal button in position and remains in the eye for three months to one year. The ophthalmologist often removes the sutures a few at a time as HEALING progresses, using an ophthalmic anesthetic to numb the affected eye, depending on the rate of vision improvement. Some sutures may remain in place indefinitely.

Full recovery typically takes about a year. Some people will have ASTIGMATISM and require CORREC- TIVE LENSES following corneal transplantation, resulting from irregularities in the shape of the cornea that develop during healing. Corneal trans- plantation may correct another VISION IMPAIRMENT such as HYPEROPIA (farsightedness) or MYOPIA (near- sightedness) because the OPERATION changes the shape of the cornea.

The most common complication of corneal transplantation is rejection of the transplanted cornea, which occurs overall in about 15 percent of corneal transplantations. Rejection is most likely to take place in the first two years after the operation. Early detection and prompt treatment with ophthalmic CORTICOSTEROID MEDICATIONS can reverse the rejection process. Signs of rejection include

• diminished VISUAL ACUITY

• PAIN

• redness of the eye

• PHOTOPHOBIA (sensitivity to light)

Other complications that can occur include INFECTION and bleeding within the eye.

See also ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION; PHOTOTHERAPEU- TIC KERATECTOMY (PTK).

corrective lenses Eyeglasses or contact lenses that alter the focal point of the lightwaves entering the EYE to correct REFRACTIVE ERRORS of vision, including HYPEROPIA (farsightedness), MYOPIA (near- sightedness), ASTIGMATISM (blurred or distorted vision), and PRESBYOPIA (age-related hyperopia). The eye’s natural focusing structures, the CORNEA and the LENS, gather lightwaves and refract (bend) them toward their centers. The cornea refracts the lightwaves first. The lens, which can thicken or flatten to refine its focal efforts, refracts the some- what focused lightwaves that come to it from the cornea. In normal vision, this sequence results in the focal point of the lightwaves striking the RETINA.

When refractive errors exist the focal point falls in front of or behind the retina, resulting in blurred images. Corrective lenses add a third level of refraction to compensate for the error, bending the lightwaves before they enter the cornea to realign their focal point. The direction of refraction depends on the refractive error:

• In myopia, the focal point falls short of the retina. A lens that corrects for myopia bends the lightwaves inward, narrowing the span of light as it enters the cornea to lengthen the focal point. Such a lens is thicker at the edges than in the middle (concave); it is a minus spherical correction.

• In hyperopia, the focal point extends beyond the retina. A lens that corrects for hyperopia bends the lightwaves outward, broadening the span of light as it enters the cornea to shorten the focal point. Such a lens is thicker in the center than at the edges (convex); it is a plus spherical correction.

• In astigmatism, irregularities in the surface of the lens cause a second focal point. A lens that corrects for astigmatism refracts along a specific axis, realigning the lightwaves. This is a cylinder correction.

Corrective lenses can, and often do, combine spherical and cylindrical corrections. A multifocal lens further incorporates a correction for presbyopia in the form of a bifocal, trifocal, or progressive lens. The bottom of the lens is a plus section,

added to the corrective prescription, that accommodates the limited ability of the lens to focus on near objects (such as when reading).

Eyeglasses

Eyeglasses are plastic resin or polycarbon, and less commonly glass, lenses ground to the thicknesses and shapes necessary to achieve the desired refractive specifications. Because eyeglasses are external to the eye, they can correct for a broad range of refractive errors and are the most common means of refractive correction. Eyeglasses also can contain tints and dyes that change their color; some have additives that provide protection from ultraviolet light. About 85 percent of people who have refractive errors of vision wear eye- glasses to correct them.

Bifocal and trifocal eyeglasses have a clear shift (sometimes visible as a line on the lens) to the presbyopic correction; a progressive lens transitions to the presbyopic correction. Reading glasses such as those available without an eye care practitioner’s prescription, are magnifying lenses that enlarge close objects, requiring the lens to make less of an adjustment to bring them into focus. How well reading glasses work depends on whether there are refractive errors that remain uncorrected. With aging, most people develop at least a small degree of astigmatism, which can result in blurred or distorted images not related to presbyopia.

The primary risk of wearing eyeglasses is trau-matic injury due to a blow that strikes the glasses. The energy of such a blow concentrates initially at the contact points on the NOSE. The frame may break, causing lacerations to the face. Of more significant consequence is a blow that breaks the lens, which can result in vision-threatening injury to the eye. Polycarbonate lenses have the highest inherent shatter resistance; plastic resin and glass lenses should have shatter-resistant coatings or additives. People who engage in physical activities such as ball sports should wear polycarbonate eye- glasses or custom protective eyewear.

Contact Lenses

Contact lenses fit directly onto the eye, covering the cornea. There are two basic kinds of contact lenses in use today: gas permeable (hard) and hydrophilic (soft). Gas-permeable contact lenses float on a layer of tears over the center of the cornea and often are the contact lens of choice to correct for moderate to significant astigmatism as well as KERATOCONUS, a condition in which the cornea’s center bulges outward. Gas-permeable lenses also can correct for mild to moderate myopic and hyperopic refractive errors. Made of rigid polymers of fluorocarbon and polymethyl methacrylate, gas-permeable lenses allow oxygen molecules to pass through but do not absorb moisture from the eye. Hydrophilic contact lenses cover the entire cornea and can correct for mild to moderate myopia and hyperopia. Soft and flexible, hydrophilic lenses contain a high percentage of water and draw additional moisture from the tears to remain hydrated. A special kind of hydrophilic lens, the toric lens, is necessary to correct for astigmatism. A toric lens has varying thicknesses that compensate for corneal irregularities to correct refraction.

Contact lenses can incorporate correction for moderate presbyopia, though this tends to be a less satisfactory approach than eyeglasses. There are two methods for accommodating presbyopia with contact lenses: progressive or bifocal lenses and monovision. Progressive or bifocal contacts function much the same as progressive or bifocal eyeglasses, with the lower portion of the lens containing the presbyopic correction. Because contact lenses shift position on the eye with blinking and when the wearer alters the angle of the head (such as when lying down), the presbyopic correc- tion may not remain in an effective position. Monovision takes the approach of modifying the BRAIN’s interpretation of visual signals. One eye, usually the dominant eye, wears a contact lens with the refractive correction. The other eye wears a contact lens with the presbyopic correction. The brain learns to distinguish which signals to inter- pret, accepting those from the dominant eye during normal visual activities and those from the other eye when reading or doing close-focus work.

The primary risks of wearing contact lenses are damage to the cornea and INFECTION. Even hydrophilic lenses can irritate the cornea and cause corneal ABRASIONS, particularly in dusty, windy, or dry environmental conditions. Contact lenses tend to accumulate protein deposits that cause irritation. Most hydrophilic lenses are disposable, so frequent replacement helps minimize this as a problem. The optician may need to clean or gently grind the surface of gas-permeable lenses to clear away deposits. Contact lens hygiene, including diligent HAND WASHING before handling lenses and storing lenses in the appropriate disinfectant solution, is essential.

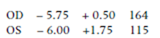

Reading a Corrective Lens Prescription Optometrists and ophthalmologists measure refractive errors in diopters, a representational scale of the distance in front of or behind the eye’s lens the focal point of lightwaves entering the eye must shift to allow the light waves to clearly focus on the retina. The larger the diopter number, the more the lens refracts, or bends, the light. A corrective lens prescription represents the diopter as

minus or plus, according to the direction the correction shifts the focal point. For example, the following prescription corrects for myopia and astigmatism:

This prescription denotes different refractive corrections for the right eye (OD) and left eye (OS). The minus diopter is the spherical correction for the myopia; the plus diopter is the cylindrical correction for the astigmatism, and the last number is the axis position for the cylindrical correction. A lens with a strong correction may also include an adjustment that tilts the lens to alter its optical center, the prism, allowing a thinner lens to deliver the same corrective power or to accommodate a significant difference in the refractive correction for each eye (anisometropia).

See also REFRACTION TEST; REFRACTIVE SURGERY; VISION IMPAIRMENT.