glaucoma A serious and progressive EYE condition in which the cells at the front of the OPTIC NERVE where it intersects with the RETINA, the retinal ganglia, die, resulting in vision loss. Early diagnosis and treatment can minimize vision loss. Health experts estimate that 5 million Americans have glaucoma, though only about 2 million of them know it. Glaucoma is the third-leading cause of blindness in the United States, primarily because it remains undetected until damage to the optic NERVE becomes significant. Glaucoma becomes more common after age 65, though there is a congenital form that manifests in early child- hood (congenital glaucoma).

Until the late 1990s ophthalmologists perceived glaucoma to be the exclusive consequence of increased pressure within the eye (INTRAOCULAR PRESSURE) that caused the death of retinal ganglia cells. Current understanding of the disease process of glaucoma affirms the death of retinal ganglia cells as the cause of damage to the optic nerve, though recognizes that numerous factors, intraocular pressure being only one among them, con- tribute to this damage. About 30 percent of people who have glaucoma have normal intraocular pressure, and only about 10 percent of people who have elevated intraocular pressure have glaucoma.

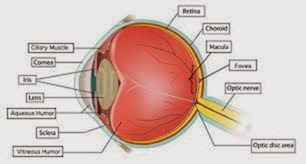

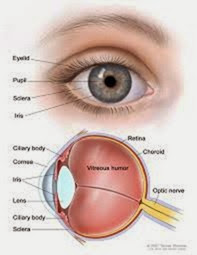

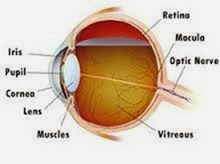

There are two general forms of glaucoma: open angle and closed angle (also called angle-closure). The designations refer to whether the channel through which aqueous humor drains from the eye, called the angle, is open but dysfunctional (open-angle glaucoma) or becomes blocked by the iris (closed-angle glaucoma). In glaucoma, the drainage angle either malfunctions (open-angle glaucoma) or a segment of the iris seals over it (closed-angle glaucoma). When the aqueous humor cannot properly drain, it causes the pressure to increase in the anterior chamber. Increased pressure in the chambers puts increased pressure on the inner eye, causing intraocular pressure to rise. Extreme or extended elevations in intraocular pressure compress the optic disk, causing nerve cells to die.

Acute closed-angle glaucoma requires emergency medical attention. Without immediate treatment, severe to complete vision loss can occur within hours of the onset of symptoms.

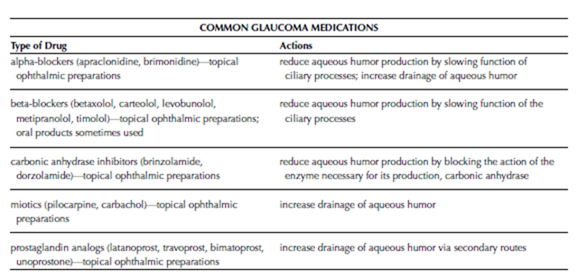

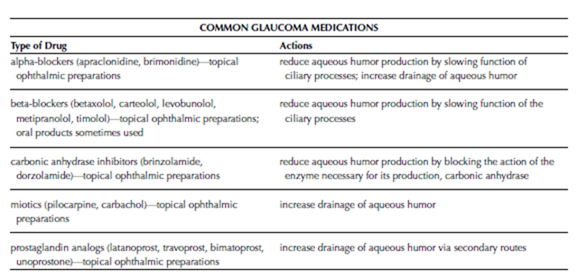

Open-angle glaucoma is chronic, progressing over years, and is the most common form of glaucoma, accounting for about 85 percent. Closed- angle glaucoma can be acute, with the sudden onset of severe symptoms, or chronic with symptoms similar to those of open-angle glaucoma. The function and dysfunction of aqueous humor drainage is the dimension of glaucoma doctors and researchers understand most clearly, and most treatment approaches target reducing aqueous humor production or improving its drainage from the eye. Less clear are the other factors that con- tribute to death of the retinal ganglia cells and corresponding destruction of the optic disk. These factors are especially significant for the 30 percent of people who have glaucoma with normal intraocular pressure. Researchers are investigating the roles of genetics, autoimmune processes, and correlations with conditions such as DIABETES and HYPERTENSION (high BLOOD PRESSURE).

Symptoms and Diagnostic Path

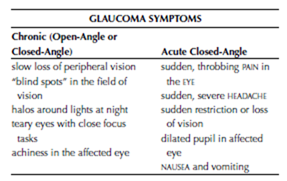

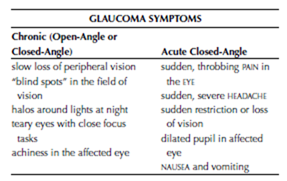

The key symptom of chronic glaucoma, open- angle or closed-angle, is the gradual and painless loss of VISUAL ACUITY and VISUAL FIELD. Often the pattern of progression begins with loss of peripheral (outside) vision. Over time the field of vision becomes increasingly narrow, which people often describe as “tunnel vision.” Other symptoms include excessive tearing (especially with close focus tasks such as reading), halos around lights at night, aching eyes, and headaches. Sudden throbbing PAIN in the eye, loss of vision, severe HEADACHE, halos around lights, and a dilated pupil in the affected eye are symptoms of acute closed- angle glaucoma.

Though eye care practitioners routinely use TONOMETRY to screen for increased intraocular pressure, this test alone is not sufficient to detect glaucoma. Detecting glaucoma requires a full OPHTHALMIC EXAMINATION including fundus examination to assess the condition of the optic disk. The ophthalmologist will also conduct a visual acuity test and a peripheral vision test. Other procedures that can help diagnose glaucoma in its early stages or quantify the extent of damage in moderate to advanced glaucoma are ULTRASOUND of the eye and OPTICAL COHERENCE TOMOGRAPHY (OCT).

Treatment Options and Outlook

Acute closed-angle requires emergency measures to relieve intraocular fluid and the accumulation of aqueous humor. Such measures typically include a combination of procedures to open the drainage angle, ophthalmic medications to lower intraocular pressure, and systemic medications to draw fluid from cells (osmotics). The ophthalmologist is also likely to administer medications for pain and to minimize NAUSEA and vomiting. Ongoing treatment with glaucoma medications or glaucoma surgery is then necessary. Ophthalmic medications (drops, inserts, and ointments) to open the drainage angle and lower intraocular pressure are the standards of treatment for chronic glaucoma of either form, and typically can control glaucoma for many years.

Surgery becomes an option to treat glaucoma that becomes advanced or does not respond to

medication therapy. Surgical treatments for glaucoma include the following:

• For iridotomy, the ophthalmologist uses an ophthalmologic laser to place a small opening in the iris. The opening provides another route of drainage for the aqueous humor and helps keep the iris from blocking the drainage angle in open-angle glaucoma.

• For trabeculoplasty, the ophthalmologist uses an ophthalmologic laser to make numerous “dots” in the trabecular meshwork—the fanlike network of tiny channels at the end of the angle that disperse the draining aqueous humor—to expand its the draining capacity.

• For trabeculotomy, the ophthalmologist places an aqueous shunt, a tiny opening from the anterior chamber through the sclera, to allow aqueous humor to drain to the outside of the eye.

• For cytophotocoagulation, the ophthalmologist uses an ophthalmologic laser to destroy portions of the ciliary processes to reduce aqueous humor production.

Early diagnosis and treatment offer the best opportunity for minimizing vision loss. It is important to diligently follow the directions for using glaucoma medications, as glaucoma requires consistent control. Appropriate treatment can slow the progression of vision loss in most people who have glaucoma.

Risk Factors and Preventive Measures

Age is the most significant risk factor for glaucoma; glaucoma is uncommon in people under age 40 and about two thirds of people who develop glaucoma are over age 65. Glaucoma is more common in people of African American and Asian ethnicity and tends to run in families. Glaucoma also is more likely to develop in people who have hypertension, ATHEROSCLEROSIS, diabetes, and severe MYOPIA (nearsightedness) and in people who take CORTICOSTEROID MEDICATIONS. Prevention focuses on regular ophthalmic examinations to detect glaucoma early in its course.

See also AGE-RELATED MACULAR DEGENERATION (ARMD); CATARACT; LASER SURGERY; VISION HEALTH.

Graves’s ophthalmopathy Changes in the EYE that occur as a result of Graves’s disease, a form of HYPERTHYROIDISM, and occasionally as a result of other forms of thyroid disease. The most prominent feature of Graves’s ophthalmopathy is EXOPH- THALMOS, an outward bulging or protrusion of the eyes that often is the first indication of Graves’s disease. The exophthalmos results from enlarged extraocular muscles (the muscles that move the eye) and edema (swelling due to retained fluid) in the tissues around the eye and within the ocular orbit (eye socket). This circumstance restricts the ability to move the eyes, particularly upward and side to side, as well as to close the eyelids. Graves’s ophthalmopathy can involve only one eye (unilateral) though most often involves both eyes (bilateral). Symptoms and consequences range from mild to severe, with about 5 percent of people experiencing substantial loss of vision that may include loss of the eye. Graves’s ophthalmopathy can appear before there are any indications of Graves’s disease, at the onset of hyperthyroid symptoms, or months to years after the diagnosis of Graves’s disease.

Graves’s ophthalmopathy presents a significant threat to vision. The swelling in and around the orbit pressures the structures of the eye and can compress the OPTIC NERVE, which can result in OPTIC NERVE ATROPHY (the death of cells in the optic NERVE) and permanent VISION IMPAIRMENT. The external pressure against the eye also raises the pressure inside the eye (INTRAOCULAR PRESSURE), which can result in GLAUCOMA. The combination of exophthalmos and restricted lid movement pre- vents the eyelids from closing completely, which allows the CORNEA to become dry. The resulting irritation and INFLAMMATION (KERATITIS) reduces VISUAL ACUITY and also exposes the inner eye to INFECTION. Though the symptoms that threaten vision eventually subside, many of the changes that result, including exophthalmos and vision impairment, are permanent.

Symptoms and Diagnostic Path

The symptoms of Graves’s ophthalmopathy include

• exophthalmos (sometimes called poptosis)

• DIPLOPIA (double vision)

• CONJUNCTIVITIS (inflammation of the inner eye- lids)

• diminished visual acuity (blurry or distorted vision)

• PHOTOPHOBIA (sensitivity to light)

• excessive tearing

As these symptoms are distinctive for Graves’s ophthalmopathy, the doctor often can make the diagnosis based on their presentation. Tests of thyroid HORMONE levels in the BLOOD confirm Graves’s disease, if not already diagnosed. Conventional OPHTHALMIC EXAMINATION and SLIT LAMP EXAMINATION allow the ophthalmologist to assess the status of vision and health of the structures of the eye. A COMPUTED TOMOGRAPHY (CT) SCAN helps assess the extent of orbital swelling and compression of the optic nerve.

Treatment Options and Outlook

The course of Graves’s ophthalmopathy seems to unfold in two stages, regardless of treatment for or status of the underlying hyperthyroidism. The first stage is the acute or active phase, during which symptoms emerge. During this stage, which extends over 18 to 30 months, ophthalmologic treatment focuses on reducing pressure on the eye and stabilizing vision, and may include

• ophthalmic lubricating drops or ointment to keep the cornea hydrated

• patching the eyes at night to protect the corneas during sleep

• NONSTEROIDAL ANTI-INFLAMMATORY DRUGS (NSAIDS) to reduce inflammation and relieve discomfort

• CORTICOSTEROID MEDICATIONS to suppress the body’s immune response

• ANTIBIOTIC MEDICATIONS to treat bacterial infection of the eyelids (BLEPHARITIS), conjunctiva (conjunctivitis), and cornea (keratitis)

In the second stage of Graves’s ophthalmopathy, the progression of symptoms ends. However, the changes that have occurred are permanent. Fibrous deposits replace lymphocytes in the eye muscles, maintaining their enlargement and continuing the exophthalmos. Treatment in this stage targets minimizing these permanent consequences through surgeries to relieve the pressure within the orbit (orbital decompression), reduce the size of the extraocular muscles (myectomy), and reconstruct the eyelids so they close completely over the eye (BLEPHAROPLASTY). Corneal reshaping (keratoplasty) or CORNEAL TRANSPLANTATION may be necessary to restore vision when damage to the cornea is extensive. If infection resulted in loss of the eye, the ophthalmologist will place a PROS- THETIC EYE.

Risk Factors and Preventive Measures Graves’s ophthalmopathy occurs only in conjunction with thyroid disorders, nearly always hyperthyroidism. It may appear months to several years before other clinical indications of hyperthyroidism, or a comparable time after beginning treatment for hyperthyroidism. Prompt diagnosis and treatment are essential to preserve vision, as the changes that occur with Graves’s ophthalmopathy are generally permanent. An ophthalmologist should evaluate any changes in the appearance of the eyes. Regular eye examinations help screen for Graves’s ophthalmopathy as well as other eye health problems.

See also AUTOIMMUNE DISORDERS; BACTERIA; VISION HEALTH.